Preface

The conflicting parties in Syria have failed to achieve absolute deterrent victories that might have allowed one side to impose its ambition at the expense of the other. This made a consensus political settlement the best option to end the existing "attrition".

While the Astana talks succeeded to establish a relative settlement of the Syrian crisis in favor of Russia, the Syrian regime and Iran at the expense of Turkey and the Syrian opposition’s ambitions aimed at overthrowing the Syrian regime, the Syrian crisis has reached the stage of "necessity" to resolve the Syrian opposition which has been thrust from each part of Syria into Idlib. Since Turkey has direct and indirect control over a large part of Idlib Province and the northern countryside of Aleppo, the question on the table is: What are the scenarios for the fate of Turkey’s presence in the Syrian north?

The importance of the proposed paper stems from addressing the most prominent scenarios that may determine the fate of Turkey's direct presence in Syria using a descriptive approach to analyze the state of relations between Turkey and the other key actor states in the Syrian file namely; Iran, Russia and the United States of America. The paper then will analyze the course of these relations in order to estimate the Turkish position regarding its presence in the Syrian north, Idlib and its surroundings on a strategic level.

First: The State of Relations between Turkey and Key Actor States

1. Turkish-Russian Relation

Since 2011 and despite the sharp differences in political visions, Turkish-Russian relation have been characterized by pragmatism based on a "policy separation" strategy by seeking to neutralize economic relations away from the field of political competition. Both countries have sought to restore their international or regional role in the international arena since the beginning of the third millennium. Undoubtedly, the reflection of the political rivalry on their existing economic cooperation would harm the endeavors of the two sides. Also, the Turkish-Russian economic cooperation is based on solid intersecting economic ties that force both parties to neutralize political disputes for fear of the collapse of these ties, and therefore the incursion of heavy economic losses.

Economic ties between the two sides have emerged mainly through Turkey's import of 58% of its natural gas needs from Russia . And perhaps the activation of the blue line between the two sides in 2003 is the main reason for Turkey's huge reliance on Russia in this field. Russian tourists make up the second largest group of tourists and investors in Turkey. In addition, Turkey is Russia’s second partner after Germany in terms of the size of its trade exchange that amounted to 19 billion US Dollars in 2015 .

And regardless of the close economic connection between the two sides, it is clear from their moves that they both fear a direct confrontation that they cannot withstand the diplomatic, media and economic results of. As such, they turned to indirect “proxy war” for the issue to be solved via the sides they have worked to support.

However, the equation that both sides have relied on was insufficient to avoid the deterioration in relations after the Turkish forces brought down a Russian warplane on 24 November 2015 on the basis the Russian aircraft violated sovereign Turkish airspace. This incident resulted in a crisis that continued for around nine months for relations to normalize again in August 2016. Several factors resulted in the return of relations, and perhaps the most important are:

a) The Motive of the Turkish Stand

• Strategic Economic Fears: Turkey was afraid that Russia persisting in its sanctions may reach the point of cutting off gas supplies or reducing the quantities exported. It also noted huge economic losses due to the absence of Russian tourists and Russia's boycotting of Turkish goods, and curtailment of procedures for Turkish investment in Russia.

• Concern that the crisis would be transformed from a “bilateral crisis” to a “regional crisis” as Turkey was attacked diplomatically and in the media in some Central Asian countries, such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and clashes erupted between Azerbaijan, Turkey’s historical ally, Armenia, Russia’s historical ally. Turkey feared Russia transferring the conflict by supporting Armenia against Azerbaijan in revenge for Turkey’s military and diplomatic proximity to the Ukraine.

• Turkey feared that it would be isolated from any solution reached in Syria: States can achieve national interests, in part or in absolute terms, through policies of cooperation and alliance, but policies of political and military competition or mutual isolation always results in clashes. In case of a policy of isolation, each side feels that the other is trying to entrap them and is designing conspiracies against them so neither is able to achieve their interests. This is what happened with Turkey, as it was cut off from intelligence and diplomatic coordination with Russia, and thus failed to intervene positively diplomatically and militarily in Syria. With the rise in the number of international meetings concerning the crisis, Turkey became increasingly concerned that it would not be able to achieve its goal of removing the threat of ISIS from its borders and curbing the Kurdish expansion along its borders especially after Russia also provided support for the Kurdish expansion. These factors increased Turkey’s desire to speed up its reconciliation with Russia with the aim of of maintaining the balance of power by containing Russia from rapprochement with the Kurds at the expense of Turkey’s interests.

• Turkey was frustrated by the International Coalition and NATO’s procrastination in fighting the “terrorist organizations” according to the Turkish classification: After Russia prevented warplanes from entering the Syrian airspace, Turkey compensated for this imbalance by expanding its cooperation with the International Coalition and the United States of America to establish military training camps that provide high-quality training to some moderate opposition factions. In May 2016, Turkey presented opening the Incirlik Base to the USA to attract American cooperation, on condition the USA did not provide support for the Democratic Union Party (PYD) (which Turkey classifies as a terrorist organization). The USA’s moves did not meet the Turkish government’s hopes. According to statements by the Turkish government, the USA used Incirlik Base to provide military and logistical support to the PYD which Turkey considered a lack of commitment by the USA to its pledges. This required the adoption of new policies outside the equation of the relationship with the USA.

• International Attitudes towards the Failed Coup Attempt: Turkey saw that the position of the USA and the European Union (EU) was negative while Moscow’s position was positive despite the strained relations between the two countries at the time. This issue encouraged a dramatic new page in relations between Moscow and Ankara after the coup attempt.

b) The Motives of the Russian Stand

On the other hand, Moscow has several motives that make it overcome many of its fundamental differences with Ankara, and move towards building a political partnership with Turkey in Syria and an economic and political partnership with Turkey at the regional level. The most important of these motives are:

• Sharing Turkey's feels regarding the American evasion and the USA’s desire to achieve influence at the expense of the interests of the other actors. Russia felt the strategic danger of the Kurdish Protection Units taking control of northeastern Syria under the American flag.

• Russian vision aimed at reaching a political solution that reflects its field superiority on the one hand and neutralizes Washington on the other. This requires partnership with a strong regional actor who can act as a guarantor or at least engage with the political and armed opposition and who has some interests in Syria that intersect with Russian interests.

• Economic motives: Russia also suffered from boycotting Turkish goods. It suffered from a rise in prices as a result of its reduced revenue given it largely depends on energy exports. The EU imposed sanctions also affected it. Since 2015, the two countries have been able to agree on several strategic economic projects, the returns of which may redress any gaps between their political interests.

• The Turkish and Russian sides have several of common points of interests in Syria. Both sides wish to achieve lasting stability in Syria, organize a political system that embraces all sects and divisions of the Syrian people and preserve the unity of the Syrian territories.

2. The Turkish-Iranian Relation

The Turkish-Iranian relations did not follow the same course of the Turkish-Russians relations despite attempts by both sides and this difference may be due to the sharp clash in their respective interests in the region. The most important points of this clash are:

• Their struggle for leadership in the region and competition for the leadership of the Muslim world: As both countries have projects that transcend their borders, albeit in different form and using different tools. The conflict between the two countries over the leadership in the region has historical roots dating back hundreds of years.

• Geo-economic Competition: Iran wants to export its natural gas to Syria and Lebanon and then Europe through Iraq and northern Syria. This project hinders Turkey's goals of transforming Turkey into a global gas distribution center. It also denies Turkey its desire to contain Iran’s economic expansion in the region by forcing Iran to accept the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline Project (TANAP) line as the most suitable line to transport its gas to Europe.

• Conflicted Political Orientation in Syria: Tehran seeks to maintain the political and security regime in Damascus through which it has direct control. It seeks to ensure that no real changes will be made to the structures of the existing regime. Turkey, on the other hand, wants to restructure the regime with what would achieve its interests.

The indicators of competition between the two sides appeared through in the decline in their economic cooperation. The trade balance between the two countries decreased from (16) Billion in 2011 to (8) Billion in 2017 . Recent years also witnessed several cases of sharp media exchanges between the two countries, the most prominent came after the launch of the al-Hazem storm in 2015.

3. The American-Turkish Relationship

In recent years, relations between Turkey and the USA have been very volatile. The relationship has witnessed points that resulted in a significant improvement in relations as well as setbacks that reached the point of the USA threatening to impose sanctions against Turkey, as has been witnessed at the end of July 2018 .

The Syrian crisis is one of the most prominent points of disagreement between Ankara and Washington. Ankara believes that Washington has prevented the implementation of real policies that may overthrow the al-Assad regime and that after 2014, the USA shifted its attention to fighting ISIS at the expensive of targeting the al-Assad regime. Moreover, the USA depended on groups Ankara describes as terrorist in its fight against ISIS. Washington believes that Turkey was not cooperative enough in the war against terrorism, and that it exaggerated the issue of US cooperation with the Kurdish side in Syria at the expense of the main goal of defeating ISIS.

The differences in the Syrian file were added to differences in other files, most notably the relationship with Iran and Russia, the position towards the parallel entity in Turkey, the position towards the Palestinian issue and the relationship with political Islam in the region.

Despite the ongoing difference, the two countries managed to agree on many projects and common understandings, the most important being their cooperation in a joint operation room.

Turkey and USA’s Motives to Work Together The American motives

• The transition of the Syrian crisis to the settlement phase, and the USA’ need for Turkey as a geographical ally that may balance Western interests with Russian and Iranian interests.

• The current US administration adopts pragmatic approaches, and seeks complementary alliances that share responsibility and costs. This approach pushes Washington to coordinate with Ankara and Moscow to achieve American objectives in Syria and the region for lower costs and in a more effective manner.

The Turkish motives

• Despite Turkey’s orientation to the east in recent years, Turkey cannot break away from its alliance with the Western camp regardless of how bad or good its relationship with the USA and Europe is. Turkey is aware that its relationship with Moscow cannot be a real substitute for its relationship with NATO and specifically the USA.

• Ankara is aware that Washington is still a major player in Syria, as well as its role as a major power in the region and the world. Turkish politicians are fully aware that achieving Turkish interests in Syria will not happen through Russia alone.

• Ankara’s membership in NATO which connects it to strategic military agreements limits its movements with Moscow at the strategic level.

• Diversifying the eggs in the balance of power basket; Ankara suffered from its singular path in international alliances, so it seems to be increasingly seeking to diversify its foreign policy consensuses to use points of contention among its allies to its advantage.

Second: Scenarios of Turkish Mobilization in Idlib and its Surroundings

Discussions about the fate of Idlib have become more urgent after the Syrian regime and its allies took control of most of the areas previously outside of regime control in the south. Regime leadership figures and their allies have repeatedly made statements about the forthcoming battle on Idlib. In a statement on 26 July, Bashar al-Assad, the head of the Syrian regime, said that Idlib will be one of the priorities of the upcoming battles.

Discussions about Idlib’s fate are largely focused on scenarios about the Turkish position towards Idlib which is connected to Turkish relations with the international actors in the Syrian file.

The possible scenarios can be summarized as follows:

1. The Cyprus Devolution Scenario

The concept of the “Cyprus devolution” is quoted from the Turkish policy towards the island of Cyprus which includes Greek and Turkish citizens. The starting point for Turkey’s policy towards Cyprus was the London Convention of 1959 which granted Turkey, along with Britain and Greece, the right of military guarantee of peace on the island and the establishment of a participatory system between the Turkish Cypriots and Greece.

Based on the Convention, the areas under the control of the Guarantor states were defined traditionally whereby areas with Turkish citizens were under Turkish guarantee, Greek citizens were under Greek guarantee and Britain acts as a neutral force along the green line separating the areas under the control of the two sides.

After the signing of the agreement, Greece and Turkey did not establish military bases in Cyprus, but both sides referred to the Convention as a legal basis to conduct diplomatic moves and military operations when needed. Turkey focused on this issue several years later. In 1961, the Greek nationalists who had greater political and security control over the island, were more active in the government than Turkish citizens and were supported by Greek military gangs, began attacking Turkish citizens.

Turkey continued to denounce these attacks until 1974 when it conducted the “Peace Process” military operation, in accordance with the aforementioned military guarantee agreement. Since that date, Turkey controls the Turkish-populated areas, which account for 36.5% of the island's total area.

Due to this operation, Turkey was subjected to sanctions and made to pay heavy costs, most notably, it was subjected to a severe military and economic blockade from the West from 1975 to 1980. Turkey persevered in the face of all these challenges, reiterating its right to military action against the island and its role of protecting Turkish citizens by announcing Turkish Northern Cyprus an independent state in 1983. Although no country recognizes the independence of Turkish Northern Cyprus and the world’s continued recognition of the island of Cyprus as a single state, except Turkey still retains its actual, “de facto”, control over the northern part of the island, providing all the services and resources needed. Despite the Turkish military control of the Turkish section of the island, Greek and Turkish Cypriots move between the two parts of the island without any notable hindrances.

If we take a closer look at the process of the Cyprus devolution scenario, we can find that it means there is a geographical military division per area. This division is controlled by the actor state, but at the level of state politics, the area is recognized as single unit and its citizens have the right to move between the parts.

Considering Ankara’s status on the Syrian issue, a Cypriot-inspired “Idlib Devolution” is a possible scenario that Turkey could implement based on rights it gained at the margins of the Astana Talks as a guarantor of the Syrian settlement process. The Cypriot Devolution scenario could be implemented by propping up the armed factions and transforming them into legitimate forces that protect the areas they are present in in a manner loyal to Turkey. Based on this scenario, opposition controlled areas will be transferred into local administrative councils that meet with the government in Damascus and share power in the Council of Regions as discussions are ongoing about the possibility of including the Council of Regions in the new constitution.

In this scenario, Turkey can develop and maintain some of its military bases in its areas of deployment in Idlib as they are at present. Alternatively, it can maintain them through partial joint deployment with Russian forces or even regime forces along the international road to avoid the other side attacking those loyal to it in similar manner to what happened in Cyprus shortly after the 1959 Convention.

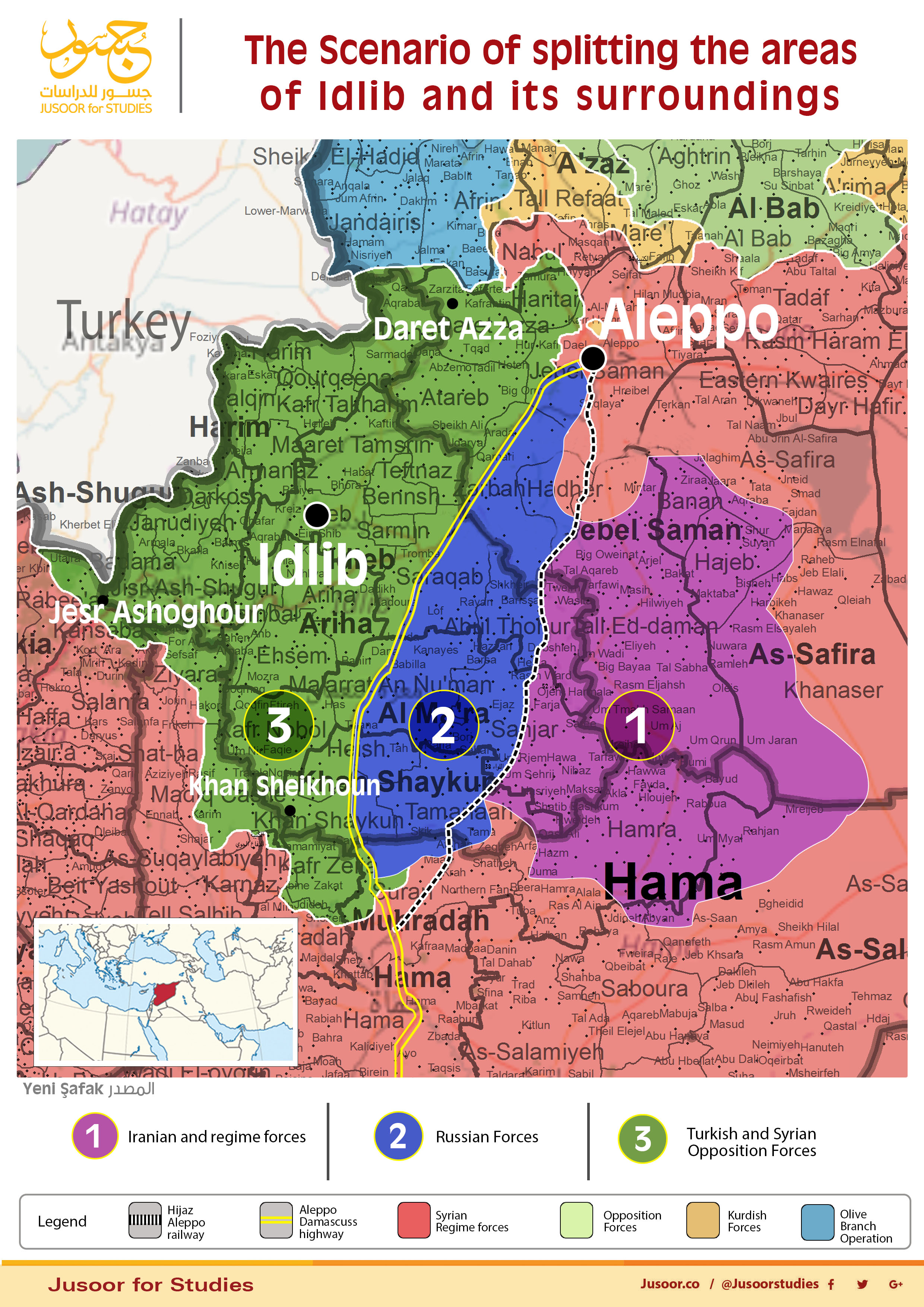

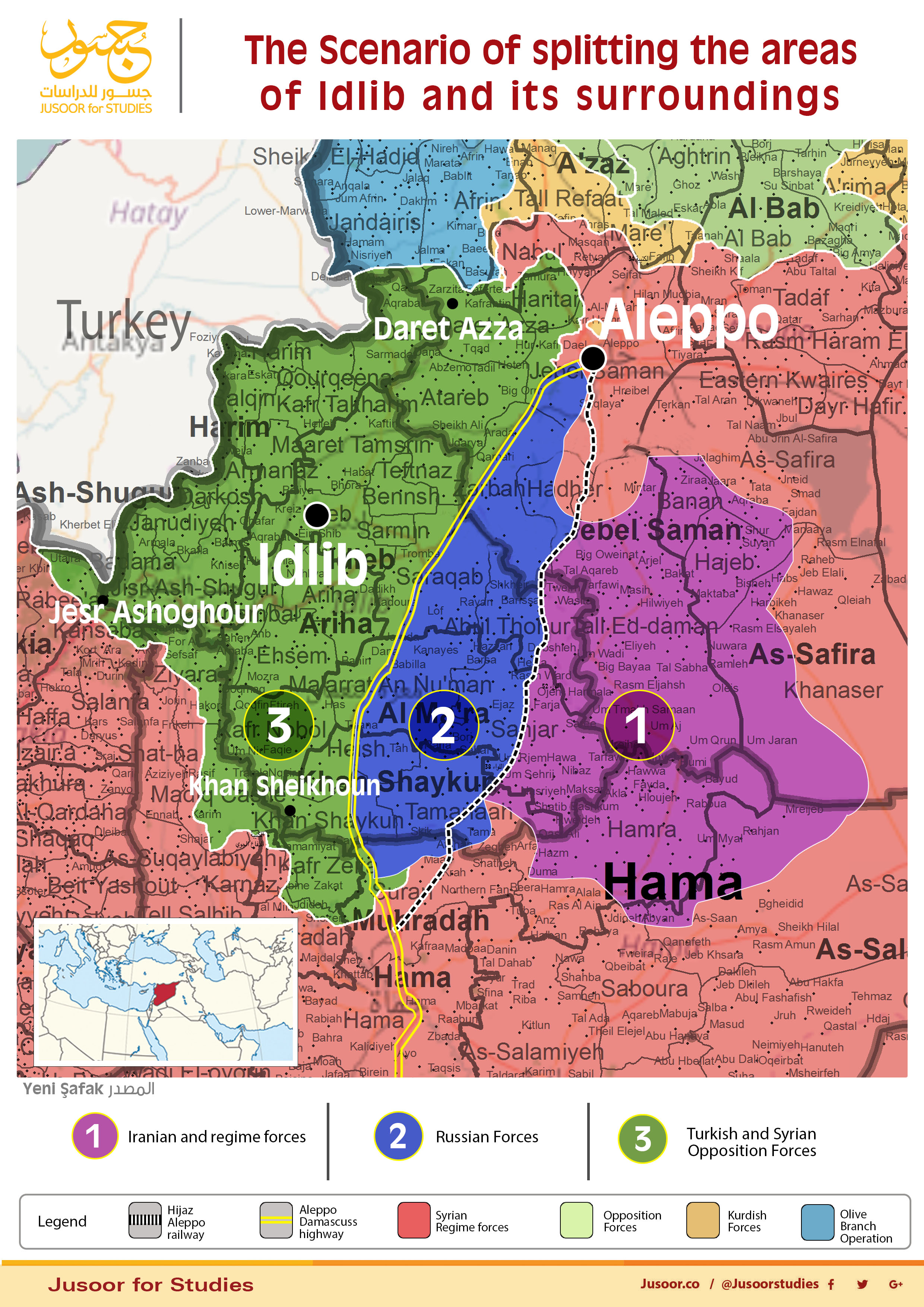

According to an article in Yeni Şafak, the Astana Six Talks that divided Idlib and its environs into three areas under Russian, Iranian and Turkish control makes Turkey’s right in the political and military guarantee for Idlib more entrenched than in other regions. This entrenchment gives it the right to mobilize the armed factions against any sides taking counter action in this territory.

According to Yeni Şafak, the areas are distribution as follows :

• East of the Aleppo Railroad: This area extends from south of Aleppo until northern Hama. Its control is transferred to the regime administration and the Iranian forces.

• Between the Aleppo Railroad and the International Aleppo-Homs Road: Initially, some of its areas are cleared entirely of “Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham” faction through fighting or propping up. Ultimately, these areas will come under Russian control. This point shows Russia as a balancing power in Syria, which increases the scenario that the areas between Lattakia, Mount Turkman and other areas and Idlib will come under Russian control.

• North and west of the international road: are subject to Turkish influence.

In light of this, Turkey may insist on its position on maintaining direct control and rehabilitating the opposition factions to establish administrative councils. In this scenario, Turkish control is concentrated in the vicinity of the international Aleppo-Hama-Homs (M 5) road, which connects Turkey to Jordan, and the Gulf. Turkey would share with Russia the responsibility of protecting this route through which Russia aims to prop up the regime economically and by extension politically.

From an international legal sense, Turkey, along with its status as a guarantor based on a common international action stemming from Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, may rely on the same article as one of its clauses states that “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security”. Turkey may invoke the existence of a power vacuum in the region and claim that the Shiite militias or even the threat of terrorist organizations forming in the region are threats to its national security, and then stay there, and support remaining on this basis. Turkey might not hesitate to seek the maximum legitimacy possible from this legislation by informing the Syrian regime, which still enjoys international legitimacy, about its forces’ distribution and presence in Idlib by means of a written paper. As it did in Olive Branch Operation. Thus, Turkey may gain, directly or indirectly, from its presence “close to the border” a legitimate legal right deriving from Article 51, which guarantees the right to act in partnership or coordination, even if only as a formality, with the state that has sovereignty.

Also, Turkey may depend on the principle of “responsibility for protection”, which includes “each State is responsible to protect its own population” and “the responsibility of the international community, with its basic organs, when the State fails to protect its population." This aim includes giving states the right to conduct military interventions with a humanitarian aim to protect the rights of peoples subjected to abuses by the State or a specific group.

In the worst circumstances, in the event the Syrian regime, supported by Russia, objects to Turkey's total or partial presence, Turkey may follow the scenario of functional thorns.

2. The Internal Agents and Functional Thorns

The functional thorns scenario is not different from the Cypriot Devolution scenario except with regard to the Turkish direct presence in the Syrian depth. This means that Turkey will turn its direct presence into the border areas while placing internal economic and social agents to establish administrative councils with Russian recognition and guarantees. These administrative councils will participate in power through the association of regions which will be approved by the proposed Russian draft constitution for Turkey. The councils also will control the economic cycle and the opposition factions will be propped up within a police force or a loyal army in Turkey’s “backyard" areas. The completion of this scenario may be highly dependent on the National Coalition, and the newly naturalized Syrians.

This part of the scenario largely simulates what happened after the withdrawal of the Syrian army from Lebanon where Hezbollah, which was given agency to become the highest political force, was in the process of completing political and indirect political dominance. But the difference between Hezbollah taking agency and Turkey’s giving agency to Syrian parties is the limitation of the geographical areas and the objective.

Turkey may retain a number of its military bases in the border areas to enhance the capabilities of internal agents to secure the objective and ensure that they can counter any Iranian militias or the Syrian regime’s movements especially in case settlements conflicted strategically speaking. In addition Turkish intelligence will absorb the functional thorns which mean "Jihadist groups", such as Tahrir al-Sham and the Turkistan Islamic Party, that is organically and militarily linked to Tahrir al-Sham, to exploit these as a tool against competitors. Those thorns may be present in mountains, caves, desert and seam zones and they are easy to absorb by granting them positions in administrative councils that these group classify as centers for launching jihad in Syria or any other region of tension in the event of regional changes. These groups also view Turkey from the lens of a “shared Sunni identity reference” and consider it as an accepted “backer”.

3 . Complete Withdrawal Scenario

Based on this scenario, Idlib will be exposed to Russian attacks, and the scenario might be achieved by putting pressure on Turkey to hand over the dossier or through Turkish-Russian negotiations that would insist Turkey fully hand over its Syrian dossier after being subjected to international pressure and taking into account the lack of strategy in Idlib province. This scenario would perhaps happen in exchange for Turkey achieving gains in other points or areas. The scenario involves agreement with Russia to act as a guarantor of the settlement process in Idlib along with establishing local councils that include the opposition, and prevent the pro-Iranian Shiite militias from approaching Turkey’s borders. This scenario resembles the scenarios agreement up by Jordan and Israel with respect to Daraa and Quneitra.

However, this scenario seems difficult to achieve for several factors:

1. Turkey’s fear that Moscow changes its priorities at the strategic level: Turkey perhaps realizing that its alliance with Russia is a limited geographical and technical alliance that came into place due to a necessity to reach “a consensual solution” following the failure of reaching the “zero-sum solution”.

2. Turkey is not willing to lose an important pressure card against Russia before it secures its nationalist interests in ending Syrian Kurdish ambitions of independence. In addition, Turkey must settle the crisis to include the return of refugees and the start of reconstruction process that Turkey expects a good share of.

3. The Turkish political will that is more confident and enjoys relatively “self- reliance” making Turkey more capable of maneuver.

4. Turkey’s relative ability to influence several functional thorns especially Tahrir al-Sham and the Turkistan Islamic Party.

5. The possibility of pressuring Iran, Turkey’s biggest regional rival, in the Syrian dossier by hinting at implementing the economic sanctions imposed by the USA especially when Turkey has a real desire to curb Iranian influence in Syria.

6. Russia’s current need for Turkey for the governance restructuring process in Syria at a constitutional strategic level that ensures the end of crisis in the long term. For Russia, while the Syrian opposition has been reined in, this has not happened in a complete or strategic way that the opposition would not turn into “sleeper cells” in Russian-controlled areas. Hence, Russia still needs Turkey to complete the reining process. Furthermore, Russia needs Turkey to complete propping up the Syrian regime economy’s by opening the Aleppo-Homs-Hama line. Russia also depends on Turkey as a geostrategic location to be used as a logistical station to return to, employ refugees from and ensure the supply reconstruction materials. In addition, Russia desires to close the S-400 deal, the nuclear reactor construction deal and the Turkish Steam gas pipeline project without obstacles or delays. To achieve its objectives, Russia may be forced to move away from this scenario and to satisfy Turkey in the framework of a win-win deal.

4. Land Swaps Scenario

This scenario is based on Turkey yielding a number of areas in Idlib in exchange for border areas east of Euphrates in Raqaa and Hasakeh and others. This scenario originates from Turkey’s real national security threat in places where Syrian Kurdish groups’ intersect with Turkish forces and in areas with high Syrian Kurdish density that may enjoy a cultural or administrative economic autonomy with the Turkish Kurds densely populated areas. There are several field political indicators to this scenario. The most important are:

• The USA cancelling the idea of establishing a border army that was expected to be formed by the Syrian Democratic Forces with 30000 soldiers deployed along the Turkish-Syrian border.

• The Turkish-American agreement on Manbij and its vicinity which opens the door for Turkey to maneuver in the area with Russia and the US to serve its interests. It is necessary to consider the Russian-American agreement and both parties’ need for Turkey to coordinate the return of refugees, reconstruction and complete the settlement process in what serves US and Russian interests.

This scenario might be realistic and can be partially achieved, but it seems that there are factors that may hinder its implementation such as Turkey yielding significant part of its, direct or indirect, influence in Idlib. These factors are:

• Concern that this scenario might cause a refugee crisis that Turkey and EU do not need.

• The question of why Turkey would give up a geographical security card close to “Latakia” (an area close to the regime’s heart) and Russia’s vital bases on the coast. On a strategic level, Turkey can use these to pressure Russia in the settlement process.

• Talk about understandings between Russia and the Autonomous Administration controlling the densely populated Kurdish areas north eastern Syria. These understandings included the removal of Abdullah Ocalan photos from public institutions in the Autonomous Administration areas and employees’ affiliation to public institutions within the Damascus administration. The understandings included the Syria Democratic Council, the political wing of Syrian Democratic Forces, opening offices in Damascus and other key cities. The understandings indicate that Russia and American agree on the start of rehabilitating these areas according to political perceptions far from military and security complexities that could be invoked by any movements by Turkey.

Third: Analysis of scenarios

It seems that the “Cypriot devolution” and the “functional thorns” scenarios are the two most likely scenarios. In other words, it is likely that Turkey will retain direct military control both in the depth of Idlib or partly in the border areas along the international road. Turkey will also keep the card of opposition control of the administrative councils. Perhaps the most realistic indicators of these two scenarios are:

1. The continuation of the Astana political talks by the guarantor states that reached the stage of forming a constitution drafting committee.

2. Russia's coordination with Turkey on the Olive Branch Operation that took place within areas under Russian air space coverage, and the pressure on the regime and its allies not to make pro-active advance towards Afrin.

3. The deployment of Turkish military bases inside Idlib and Turkey's tendency to fortify them.

4. Keeping the former Chief of Staff Hulusi Akar as Minister of Defense, and Mevlud Cavusoglu as Minister of Foreign Affairs om the new Turkish Government. Also keeping Hakan Vidan, the head of the National Intelligence Service, in his position. These figures played a major role in shaping Turkey's political and security equation in Syria indicating Turkey's tendency to continue with the same approach.

5. Threatening to end the essence of the Astana talks if the regime attacks Idlib and preventing regime forces from heading towards Idlib. Turkey has actually used force against the Syrian regime and Iranian militias on the sidelines of its operation in Afrin. That had a great effect on the Russian calculations given Russian still need Turkey to complete the settlement process in a way that ensures containing any major or minor threat posed by the opposition in the future.

6. The formation of local councils in Turkey’s controlled areas and pushing the Syrian Interim Government towards Syria.

7. Closing the Kafraya and al-Fuaa dossier to put an end to the tension in the city.

On an analytical level, it is possible these two scenarios may become reality due to the following factors:

• Turkey having influence with functional groups such as Tahrir al-Sham and the Turkistan Islamic Party that outweigh other opposition factions that might tend to reconcile with the Syrian regime or Russia.

• Its consistency with the American vision of the solution, described above, which is based primarily on the establishment of an elected local administrative councils that enjoy “democratic administrative independence” from regime-controlled areas, according to Rand Corporation. The USA’s implementation of this vision has emerged through the establishment of several councils in Raqqa City and in areas it controls in the vicinity of Deir Ez-Zor. Within the framework of this vision, the US needs areas close to Turkey and Iraq to avoid pressure from human rights advocates about the legitimacy of its presence in Syria. For the US, Turkey represents a strategic geographical location from which it can follow the course of the settlement process in Syria to the best of its interest. The US need for Turkey as a strategic geographical location and Turkey's need for the US as a supporter of its movements in Syria show mutual interdependence.

• The absolute consensus between Turkey and Russia and Iran, the other guarantor states, based on the need to preserve the unity of the Syrian territory. Turkey plays a significant role in implementing this scenario by pressing the American and European sides against the separatist Kurdish movements. This may be part of the factors that strengthen the implementation of one or both of the scenarios mentioned.

• The possibility of Turkey moving the opposition factions, the functional thorns, against any attacking forces, and enhancing their fighting capabilities with strong weapons.

• The significant vitality of both scenarios for Turkey which fears a massive refugee crisis.

• Turkey is keen to implement these scenarios fearing the continued attrition of its loss of national interests compared to Russia and Iran. For Turkey, Iran and Russia remain its geopolitical and economic rivals while being central to it at the regional and international levels despite the relative tactical consensus that exists today. This balance is especially important in light of Turkish fear of the possibility of Russia providing the Iraqi Kurdistan Government with a corridor towards the Mediterranean which will enable them to export oil abroad. Iraqi Kurdistan Government fell into blockade between Iran and Turkey which pushed it to search for an alternative. The Rosneft agreement, signed in February 2017 and then in June 2017, enables Russia to share production of five oil areas in the Kurdistan Region with 400 million US Dollars investments. Roseneft announced the start of negotiations with Kurdistan Government to fund a gas pipeline project. There is no doubt that within the context of Russia’s political control of Syria, Turkey fears Russia's possession of Kurdistan region oil export card, and thus Kurdistan’s independence. Also, Turkey fears other losses that Russia and Iran might case due to their control of international trade lines that would allow them both to gain the reconstruction card in Syria and leave Turkey outside the deal.

These two scenarios are in line with the Russian vision of the solution, that is based on an active actor agency that governs other parties. In this way, Russia guarantees the highest political influence over one region which may lead to decentralized governance. The term “Chechenization” is already used to describe this Russian strategy.

In short, “Chechenization” refers to the imitation of the solution that ended the Chechen crisis. After assuming power of the Russian Federation at the end of 1999, President Vladimir Putin, turned the conflict from a Russian-Chechen conflict into an internal Chechen conflict. He was able to split the Chechen factions to serve Russia’s interest and enable Russia’s eventual complete control of the region.

The key to this scenario was to hold agreements with some influential warlords and to grant them prestigious political and social positions on the condition that they accept Russian influence over the region of Chechnya. In this manner, Chechnya eventually became a federal state within the Russian Federation. Russia infiltrated Chechen rebel factions through the Chechen rebel Mufti Ahmed Haji Kadyrov, who created a deep internal divide, manifested by the emergence of binary “loyal rebel” and “disloyal rebel” who Russia fought.

Perhaps Russia chose Turkey as the agent due to Turkey's popular acceptance among the Syrian factions in comparison to other states that have funded factions. In addition, Turkey’s geographical proximity to the opposition controlled areas and its international status as a center in the region that Western countries refer to must have been considerations.

Through this equation, Russia has become a “balancing force” between Turkey and the opposition on the one hand and Iran, the regime and its allied militias on the other. This position enabled Russia to control the balance of power in Syria. Russia uses that balance to shift between Iran and Turkey in a way that achieves what it wants. In light of this, it is possible to implement the "Cypriot Devolution" scenario which includes Russian forces separating between Turkish deployed forces and regime forces.

A closer look at the Russian vision of the solution, makes it clear that the first stage of dividing the opposition has been achieved. Russia now is entering the stage of searching for an agent to maintain the solution process at a strategic level. Turkey's presence in Idlib, both directly and indirectly, seems vital to Russia's vision of a solution.

While we have nominated both scenarios in the short and medium term, the “functional thorns” scenario becomes the best scenario at a strategic level. The international equations might change and the Syrian state, whether in its present form or in a different form, may become more powerful and able pressure on Turkey to restore all Syrian territory to Syrian authority, regardless of the presence of “transnational areas” whose administration or sovereignty are shared by more than one authority. Hence, Turkey might insist on the implementation of this scenario, which carries a new form of governance in order to ensure its interests in the north of Syria as a whole.

Fourth: The Challenges of Implementing the Scenarios

The occurrence of the two scenarios mentioned maybe more realistic, but there are some challenges that Turkey may face while attempting to implement them:

1. Regional Challenges

• Russian rotation: Russia might fulfil the common international relations Western saying of “whoever allies with Russia is a loser” making Turkey a loser by turning away from the previously drafted agreements to pressure Turkey to hand over agricultural suitable areas. A shift in Russian action, if it occurs, might be manifested in supporting regime movements or by opening the way for ISIS cells to move towards Idlib from Aqrabat Mountains in the eastern countryside of Hama as it did in October 2017 .

• Iran's defiance of Turkish ambition and Turkey’s reliance on the economic card as a pressure tool, and supporting the regime through its militias.

A Russian-American consensus that ignores Turkish interests but still ensures that the US maintains its indirect influence through administrative councils in north-eastern Syria, and downsizes Iran's influence in Syria to avoid higher costs. Such a consensus may also serve as a revenge against Turkey because it refused to comply with the US sanctions on Iran. This challenge depends on Trump's ability to overcome US institutions that do not see a Russian-American cooperation acceptable.

2. Dealing with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham

The biggest challenge for Turkey in Idlib appears to be Tahrir al-Sham. In light of this, the scenarios that Turkey can follow to avoid the dilemma of al-Nusra Front are as follows:

A. Somalia Scenario

The Somalia scenario is centered on the rule of Islamic Courts that started in Somalia in 1991. The rule of the courts began with two entities; the first combines Sufism and the organization of Ahl al-Sunnah, al-Jama'a and the Muslim Brotherhood, and other “moderate” groups. These groups usually tend to seek peaceful settlement processes. The second is based on the “Salafist Jihadist” group that tends to “overcome” or resort to “zero military resolve”.

The Islamic Courts have contributed to the establishment of security at more than one point in Somalia. They were supported by Somali scholars, tribal leaders and businessmen, especially in the absence of any fanaticism in their internal and international orientations. This support continued until March 2004, when “Mujahideen Youth movement” with Salafist background emerged by separating from the “Islamic Courts” and accused the courts of “appeasing the enemies”.

Despite the Supreme Transitional Court calling for Ethiopian forces against the Islamic Courts in December 2006, the Islamic Courts maintained their moderation until the Somali parliament, with regional and international support, elected its leader Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed as President of Somalia. After taking office, Sheikh Ahmed dissolved the Islamic Courts. This move caused a major rift in Somalia which gave moderate groups the opportunity of political participation at the expense of excluding the radical Salafist movement that become an internal and external militant force.

If we are to project the Somali scenario on Idlib, the scenario would include Turkey’s propping up Tahrir al-Sham by pushing a large part of its leadership wings to participate moderately in administrative authority and excluding extremists and limiting their activity. Turkey can achieve this through the process of “soft disintegration”. Turkey will communicate with Tahrir al-Sham’s “non-grassroots” factions and its “legitimizers”, religious figures who may support the Turkish vision, and work to attract influential economic and social leaders within the group. Some of them may accept this in return for maintaining the group’s position and protection by Turkey.

But the main obstacle to this scenario will be the extremist wing within the group that rejects the political solution. If efforts to adapt this wing fail, the extremist wing will resort to the “Afghanistan scenario” of seeking refuge in the mountains like al-Qaeda did in Afghanistan. The wing would then resort to hit-and-run style operations from their hideouts in the Badiya or mountain areas.

B. The Gaza Scenario

This scenario is based on the theory that Tahrir al-Sham will reproduce the scenario of Hamas' control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, by continuing to gain popular legitimacy by targeting the regime forces and controlling the border crossings. But this scenario appears unrealistic for several reasons:

• Hamas is not Tahrir al-Sham: When Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, it was a political party that won about 70% of the votes in the legislative elections. Thus Hamas established its legitimate right to resist the elements that were trying to delegitimize it. Tahrir al-Sham lacks this both local and international legitimacy. Also, Hamas did not pose a strategic threat to Egypt's strategic national security. Egypt opened Rafah Crossing because it saw that Hamas has effective control with public electoral acceptance and to avoid the deterioration of the situation in the Gaza Strip. At the same time, Egypt is not directly involved in the internal Palestinian crisis. Also, Hamas is a national liberation movement that is relatively acceptable to the countries in the region, in contrast to Tahrir al-Sham that represents a jihadist ideology. These crucial differences push Turkey to reject this scenario because it could open Idlib to Russian and Iranian attacks in support of the regime regaining control of the area.

• The difficulty of achieving economic independence: If we assume that the Salafist “extremist” wing in Tahrir al-Sham took control and removed the current moderates and defied Turkey, it is impossible for this group to achieve political control followed by a sustainable economic cycle. The economy in crisis areas is based on financing the armed factions that have effective control and is not based on citizens' interests. These factions rely on smuggling, arms trade, and other methods outside the framework of organized economic activity. The economy under Tahrir al-Sham authority is unbalanced with the economy of Idlib’s residents.

In the end, for every action, there is a challenge that national states should be aware of to protect their national interests, which are already based on the awareness of politicians.

Conclusion

Today, Turkey is at a very delicate junction in the Syrian dossier and it has to choose the road with fewer dangers for its national interests. This road should be in the right direction and closer to its ambition and to the Syrian opposition, which is becoming more and more realistic.

In light of this, the course of Turkey's relations with influential countries in Syria plays a great role in formulating the solution Turkey seeks. By setting the course of its relations with Russia and Iran on the one hand, and the USA on the other, this report demonstrated that it holds tools to pressure these actors. This pressure and the various factors discussed will enable it to implement a scenario of full or partial direct control over Idlib with indirect administrative and security control.

Margins:

1- 2015 Countries from which we imported oil and natural gas in October 2015, Energy Atlas, 7/1/2016

2- 5 Graph Turkey – Russian economic relations, the BBC Turkish, 25/11/2015

3- Ministry of Commerce, Foreign Relations –Iran, 22/7/2018

4- US to hit NATO-ally Turkey over detained pastor, Trump says, Washington Post, 26/7/2018

5- Al-Assad: “Idlib is the priority of the Syrian Army and the fate of the White Helmet is either execution or reconciliation,” Russia Today, 26/07/2018

6- 25000 Soldiers to Idlib, YeniŞafak, 15/09/2017

7- Russia uses Aqrabat card against Turkey, Noon Post, 10/11/2017

8- Islamic Courts Union, Aljazeera Net, accessed 26/07/2018,