War Economy in Syria

Font Size

War Economy in Syria

Funding and inter-trade relations between the conflicting forces in syria

Funding and inter-trade relations between the conflicting forces in syria

Preface

The last seven years have caused transformations in all parts of Syria. The totalitarian state (ruling totalitarian regime) established for decades disintegrated and its influence shrank to only reach a third of the Syrian soil in 2012. Since then it has expanded again to reach around 60% in the last quarter of 2018. The state then turned into an actor among many, and different forces have emerged with each controlling an area outside state control. The forces continued to control areas to varying degrees as some forces controlled areas for 5 years until this point in time whereas other forces controlled for a few years only.

Tension characterizes the relationship among all the actors, and these forces entered into conflicts with each other. At the best of times during ceasefire periods, opposition-controlled areas experienced internal fighting within a single controlled area.

Economic life in the different regions, especially in areas outside the control of the state, did not received much focus. In these areas, there are no traditional organizational forms of state economic institutions to issue statistics and figures that indicate the economic performance. Subsequently, it is impossible to study the performance of the economy in a scientific manner.

The permanent military conflicts among all forces, and sometimes within the same area of control as was the case in some opposition-controlled areas, diverted attention from these warring parties’ economic ties. These economic relations acquired an “economic rationality” to sustain the flow of goods and services among them, but not a “political rationality” that can enable these powers to reach a settlement for their conflicts.

This research will discuss two main pillars of the Syrian war economy, namely, funding and inter-trade relations between the conflicting forces in the Syrian geography. The research aims to:

1. Review the historical foundations and rules of the economy of the Syrian war, established by the Assad regime several years before the war, and identify the developments of these foundations and rules.

2. Research the funding of the parties and conflicting groups in Syria and identify what of this funding is sustainable and its effect on the durability of the war.

3. Reveal the nature of trade relations among the conflicting parties and examine its theoretical basis, causes and the scope of its development or decline and consequently; the weaknesses and strengths of these relations.

Previous studies have addressed some of the themes examined in this research, but they were limited to specific aspects of these themes. One of the most important studies in this regard is a report published by Madad Center, a pro-regime center based in Damascus, entitled, “Features of the Economy of War in Syria” in 2010. The research focused on the idea that the war economy in its current form is incompatible with the principles of economic freedom and the capitalist system adopted by the regime. The research explained that capitalist countries must work to end this situation for the market economy to function naturally. The Carnegie Middle East Center published a paper in 2015, “War Economy in the Syrian Conflict: Solve Your own Issues”. The paper discussed the losses that the Syrian economy has suffered due to the war and reviewed the new economic situation in all Syrian regions without addressing the infrastructure for funding the conflict in Syria. The paper, prepared by Rim Turkmani and others, entitled, “Countering the logic of the war economy in Syria: evidence from three local area” published in 2015 is considered the most comprehensive study that addresses the war economy in Syria and its relation to the social structures in areas of conflict.

This research investigates the means of funding and the inter-trade relations among the conflicting forces in recent years by depending on field data.

First Chapter: Funding the War for Conflict Parties

First Theme: Funding the War for the al-Assad Regime

First: “Endorsing” State Resources in Favor of the War

Discussions about Syria's economic resources have always been restricted within Syria. At best, the “comrades” in the Baath Party talked about the high military and security spending aimed at creating a strategic balance with the “enemy”, an aim that required huge sums.

In the case of a totalitarian country such as Syria, it is difficult to know the real expenditure figures of the security and military sectors, or even the unofficial (shadow) sectors. The regime built its authority based on the resources and capabilities of the state, appointing loyal officers to the security sectors, excluding whoever was considered a threat and establishing a custom for appointments in the public sector based on “loyalty to the regime/family rather than the state.”

Syria's gross domestic product (GDP) exceeded 55 billion US Dollars (USD) in 2010, and revenues entering the state treasury increased by 20% between 2009 and 2010 to 13 billion USD, of which more than half is made through oil.

The growth in revenues entering the Treasury had been increasing annually at a good and noticeable rate in the pre-2011 period, and the foreign exchange reserve in the Syria Central Bank was more than 20 billion USD. The bulk of these resources was allocated for current expenditures and not investment. In 2011, 15 billion USD were allocated as expenditure in the budget , 60% of which were current expenditures that go to paying salaries, wages and administrative expenses that were already large due to the inflated state administration apparatus. A similar pattern is witnessed for years prior to 2011. Following the outbreak of popular demonstrations throughout Syria, al-Assad issued a decree raising salaries at a rate of 30 USD per person and at higher percentage for low salaries. The minimum wage was raised to more than 200 USD and income tax was reduced, which means higher spending and less resources in the state budget. These measures were part of an attempt to bribe state employees from the public treasury account in an effort to stop the protests that had begun days before the decree was issued.

It is not only the unofficial dealings between the security branches and the state institutions that confirm this clear “endorsement” in the service of war, but also official laws that were issued for this purpose. For example, Law No. (14) of 20/07/2016 states, “To cancel the end of service for an employee in the event the employee joins the mandatory or reserve military service.” The employee joining the military would continue to receive his salary from the state institution that he works in. Furthermore, a decision was issued to return a large number of officials to their posts and pay them salaries again, despite their exemption from military service. For example, and not exclusively, Decree No. 205 to appoint Duraid Dergham as the governor of the Central Bank of Syria. This decision was made following a decision issued by the Minister of Finance in 2011 to seize Dergham’s movable and immovable assets after his removal from his post as Director General of the Commercial Bank of Syria, and there are many other examples.

Second: Young Wolves and their Role in the Funding Process

With al-Assad’s, the son, accession to power, several changes took place in the pillars of the regime as well as in the form of the prevailing socio-economic system. Practically, socialism came to an end with the transformation towards the market economy. Several senior state officials (known as the men of the old guards) started to move away from the state either for reasons related to age or other considerations. On the other hand, the sons the old guards become closer to the state. These sons depend on the wealth, influence and social relations their fathers accumulated and established in the previous stage. Rather than enter state positions, they focused on the market and like hungry wolves ate the largest share . This group had a big role in funding the regime during the war as the following examples illustrate. Rami Makhlouf’s al-Bustan Charity funded the National Defense Militias (NDM) and cared for their families for years. The Fawz Holding Group, belonging to Samar Fawz, contributes to fully funding the military security shield forces and other groups. The Fawz Charitable Society group oversees the follow-up of the affairs of the war injured and the families of those killed in the war. Similarly, al-Muhaymin transport company contributed significantly by providing transportation and logistical support for regime soldiers.

In addition to these wolves who branched out from the authority, the old bourgeoisie - as the Baath Party called them – observed the movement opposing the regime and took a cautious and careful position from both sides in the conflict. Some of the old bourgeoisie funded both sides to maintain their gains such as well-known businessman Tarif al-Akhras, whose eldest son donated a huge sum to the rebels of Homs. This prompted al-Akhras to temporarily get his son out of Syria and pay large sums to the Military Security branch to fund its operations.

Bashar al-Assad, during a speech at Damascus University, called for involving businessmen in funding military operations. He said, “One day, we will ask each capable individual what is your role in the process of supporting the campaign ”. The speech prompted many businessmen to pay sums to support the regime and its army and to record these positions publicly in front of the security branches. In return, a number of these

investors benefited from the war as it led to many prominent business figures leaving Syria. For instance, Samer al-Fawz purchased a large number of Emad Griwati’s, a prominent business figure, assets for a cheap price while Nader al-Qali obtained government contracts benefiting from his ability to move freely outside the controlled economic landscape in 2011. Hossam Qatarji played the role of mediator in supplying the regime with oil and wheat from the Kurdish administration and ISIS-controlled areas for years. A large number of these new businessmen have contributed to regime operations with money or relations. For instance, some of them made wheat deals with foreign countries for the benefit of government agencies, and some supplied the regime with money and foreign currency.

Third: External Debt

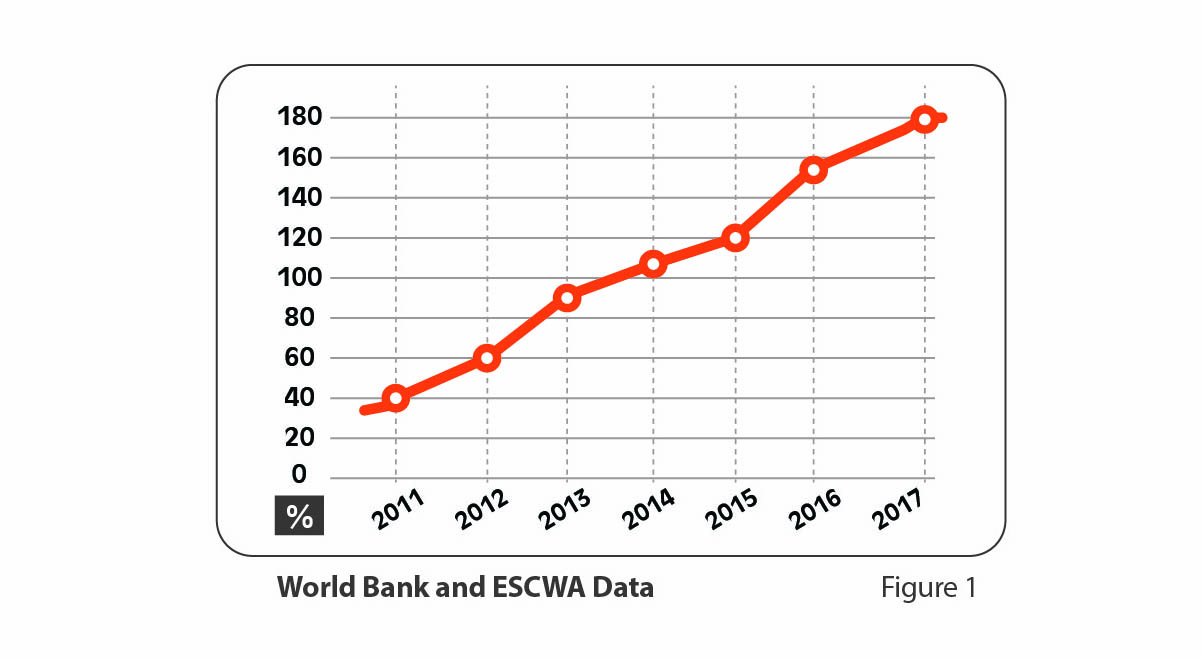

At the end of 2010, Syria's external debt was estimated at around 4 billion USD, and domestic revenues were around 10 billion USD, which constitutes 25% of the Syrian gross national product, acceptable when compared to historical events or other countries. For example, the foreign debt ratio reached more than 150% in Syria in the mid-90s. This level of debt did not remain long at these levels, as the weakening of the state's public treasury resources and the collapse of the foreign exchange reserves prompted the regime to enter into deals with Iran for multiple loans. The first loan, known as the Iranian credit line, was taken for 1 billion USD in 2013. The loan was contingent on purchasing Iranian merchandise. The number of loans increased for Syria's external public debt to reach 6.5 USD billion in 2013 , and in 2017, the regime received an additional 1 billion USD. There are also debts owed to Russia.

The World Bank and The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UN-ESCWA) estimate that Syrian public debt is more than 150% of the Syrian GDP for 2017, a figure closer to that of the 1990s. Other researchers estimate that Syrian public debt is much more. This might be true if we look at the Iranian and Russian military expenditures, which are not counted as sums on the current government, but are born by the countries exporting these military forces. These countries will in one way or another consider transferring the burden of these expenses to Syria through oil, real estate or telecommunications investments. For instance, the case of an Iranian company that was given a contract for an oil refinery east of Homs and the contract given to the Iranian mobile phone operator.

Fourth: Funding State Security and Paramilitary Forces

With the beginning of the outbreak of popular protests in Syria, forced emerged supported by the regime and armed with sticks and light individual weapons. Known as Shabiha (thugs), they participated in the suppression of demonstrations and most of their elements were affiliated with the Baath Party. Funding these forces began modestly. In Homs, Saqr Rustam (an Alawite engineer working in the management of the industrial zone in Homs, and who was expelled from Homs in 2009 based on financial corruption cases) founded the National Defense Militias (originally call the Popular Committees). Rustam started training the militia's members in Tishreen Stadium south east of Homs in the al-Nozha, majority Alawite neighborhood. They were also trained along the old Palmyra road by retired officers and subsequently with support from Iranian officers. Rustam received support from young businessmen such as Abu Ali Khaddour (owner of Abu Ali supermarket) and Fares al-Hadba (a real estate agent who later became a member in the People’s Assembly). These militias soon received support from bigger businessmen such as Rami Makhlouf through the Al-Bustan Charity. This experience was later transferred to different Syrian cities and provinces.

The most important funding for these forces came from “Tashbih operations” as the Popular Committees initially relied on kidnappings and swaps , imposing royalties at the checkpoints on cars crossing from one area to another and theft, known as Taafish operations (the looting of furniture) which later had its own special undertakers. Taafish practice led to the emergence of markets known as the “Sunna Markets” in Damascus, Homs, Lattakia and other Syrian cities. Looting the property of a village or region has become the custom and right of the faction that storms that region since it made “the greatest sacrifice” to enter. Everything is looted from the foundation of the house to the electrical wires and water taps. In some cases, the roofs and walls of houses were demolished to extract iron bars from them and sell them as scrap, thus financing the battalion or the faction.

Taafish operations were not limited to paramilitary forces but extended to the army and security forces, which carried out these operations in a systematic manner in most of the areas they controlled, especially if there were no Russian troops in the area. In 2018, these practices were widely documented in al-Yarmouk Camp, al-Qadam, al-Hajer al-Aswad and Daraa.

The security forces also used detention as a weapon to fund their elements. Regime prisons include tens of thousands of detainees held on political charges, almost all of whom have not engaged in real opposition activities (they end up in security branches and are not transferred to state prisons). Arresting those persons is a major source of income for the security branches overseeing the prisons. The security branch personnel blackmail detainees’ relatives to obtain payments from them to improve the prisoners’ conditions and transfer them to dormitories with better living conditions. Security agents also sell telephone cards, internet and other goods to the prisoners in return for amounts that are several times higher than their market price.

The summon to complete compulsory military service is another source of income. The families of those who are required to complete their military service, pay large sums to transfer their sons to certain military divisions, to fake their son’s papers or even to be able to send their sons outside Syria despite being wanted for military service.

Second Theme: Funding the War for Hayat Tahrir al-Sham

First: Spoils

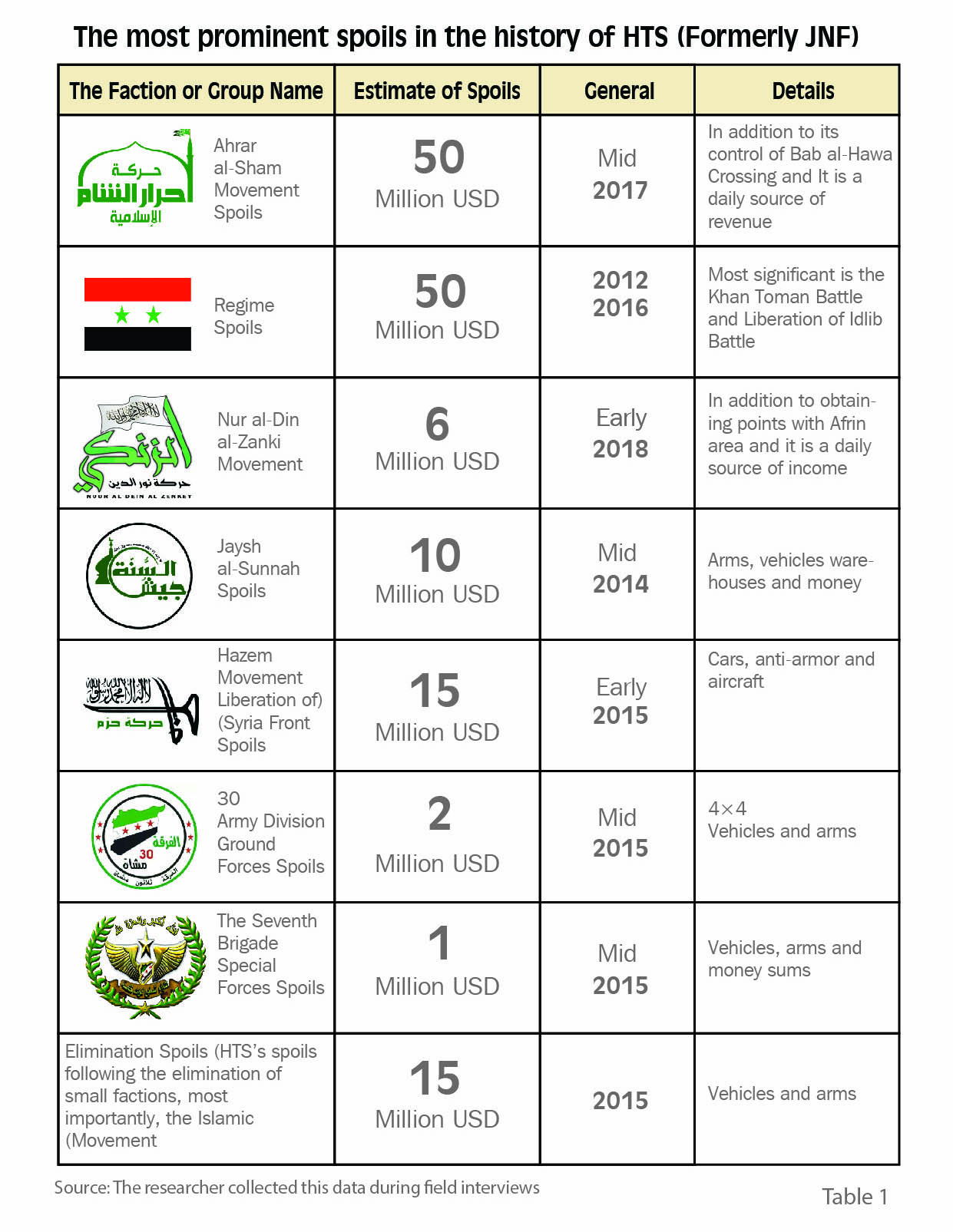

In his first appearance on Al-Jazeera Channel, Abu Muhammad al-Golani, commander-in-chief of the Hayat (formerly al-Nusra Front ), said they have not received any support from anyone and that most of their funding comes from “spoils” controlled by the Hayat (the Front at that time) and that they accept unconditional funding from businessmen and individuals.

This statement is partly true because Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s (HTS) funding primarily comes from “spoils” taken from battles with the “other” whether the regime, ISIS or opposition factions (see Table 1). In the battle at end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018 with Nur al-Din al-Zanki Movement, HTS adopted a tactic that required splitting the spoil with half going to the fighter and the other half goes to the faction . This approach earned HTS a good participation from of a large number of its fighters and other fighters who joined the HTS in anticipation of these gains. The HTS made advances in several areas.

In the previous battle with Ahrar Sham Movement in mid-2017, HTS took control of Ahrar al-Sham’s entire capabilities estimated at millions of USD. For example, in the city of Salqin alone, north-west Idlib, HTS took control of Ahrar al-Sham’s Khalid bin Walid Camp capabilities. The camp’s vehicles and arms were estimated at 1 million USD . In the same area, HTS seized a media studio equipped with advanced technologies estimated at half a million USD , and seized Ahrar al-Sham car warehouses with an estimated 2000 mostly modern cars valued at more than 20 million USD. HTS took control of Jaysh al-Sunna headquarters, one of the four factions that were running Idlib at that time and a component of Jaysh al-Fatih. HTS also took control of many small factions such as the Islamic Movement whose commander Abu Bakr was killed in HTS prisons. HTS took control of Abu Ali Wishah’s headquarters (he was linked with sheikh figures who received great support), in addition to other operations it carried out in the north of Syria. HTS has acted based on the idea of overcoming that dictates that the winner governs the area and imposes the status quo with the remaining forces present submitting to his rule.

Third: External Debt

At the end of 2010, Syria's external debt was estimated at around 4 billion USD, and domestic revenues were around 10 billion USD, which constitutes 25% of the Syrian gross national product, acceptable when compared to historical events or other countries. For example, the foreign debt ratio reached more than 150% in Syria in the mid-90s. This level of debt did not remain long at these levels, as the weakening of the state's public treasury resources and the collapse of the foreign exchange reserves prompted the regime to enter into deals with Iran for multiple loans. The first loan, known as the Iranian credit line, was taken for 1 billion USD in 2013. The loan was contingent on purchasing Iranian merchandise. The number of loans increased for Syria's external public debt to reach 6.5 USD billion in 2013 , and in 2017, the regime received an additional 1 billion USD. There are also debts owed to Russia.

The World Bank and The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UN-ESCWA) estimate that Syrian public debt is more than 150% of the Syrian GDP for 2017, a figure closer to that of the 1990s. Other researchers estimate that Syrian public debt is much more. This might be true if we look at the Iranian and Russian military expenditures, which are not counted as sums on the current government, but are born by the countries exporting these military forces. These countries will in one way or another consider transferring the burden of these expenses to Syria through oil, real estate or telecommunications investments. For instance, the case of an Iranian company that was given a contract for an oil refinery east of Homs and the contract given to the Iranian mobile phone operator.

Fourth: Funding State Security and Paramilitary Forces

With the beginning of the outbreak of popular protests in Syria, forced emerged supported by the regime and armed with sticks and light individual weapons. Known as Shabiha (thugs), they participated in the suppression of demonstrations and most of their elements were affiliated with the Baath Party. Funding these forces began modestly. In Homs, Saqr Rustam (an Alawite engineer working in the management of the industrial zone in Homs, and who was expelled from Homs in 2009 based on financial corruption cases) founded the National Defense Militias (originally call the Popular Committees). Rustam started training the militia's members in Tishreen Stadium south east of Homs in the al-Nozha, majority Alawite neighborhood. They were also trained along the old Palmyra road by retired officers and subsequently with support from Iranian officers. Rustam received support from young businessmen such as Abu Ali Khaddour (owner of Abu Ali supermarket) and Fares al-Hadba (a real estate agent who later became a member in the People’s Assembly). These militias soon received support from bigger businessmen such as Rami Makhlouf through the Al-Bustan Charity. This experience was later transferred to different Syrian cities and provinces.

The most important funding for these forces came from “Tashbih operations” as the Popular Committees initially relied on kidnappings and swaps , imposing royalties at the checkpoints on cars crossing from one area to another and theft, known as Taafish operations (the looting of furniture) which later had its own special undertakers. Taafish practice led to the emergence of markets known as the “Sunna Markets” in Damascus, Homs, Lattakia and other Syrian cities. Looting the property of a village or region has become the custom and right of the faction that storms that region since it made “the greatest sacrifice” to enter. Everything is looted from the foundation of the house to the electrical wires and water taps. In some cases, the roofs and walls of houses were demolished to extract iron bars from them and sell them as scrap, thus financing the battalion or the faction.

Taafish operations were not limited to paramilitary forces but extended to the army and security forces, which carried out these operations in a systematic manner in most of the areas they controlled, especially if there were no Russian troops in the area. In 2018, these practices were widely documented in al-Yarmouk Camp, al-Qadam, al-Hajer al-Aswad and Daraa.

The security forces also used detention as a weapon to fund their elements. Regime prisons include tens of thousands of detainees held on political charges, almost all of whom have not engaged in real opposition activities (they end up in security branches and are not transferred to state prisons). Arresting those persons is a major source of income for the security branches overseeing the prisons. The security branch personnel blackmail detainees’ relatives to obtain payments from them to improve the prisoners’ conditions and transfer them to dormitories with better living conditions. Security agents also sell telephone cards, internet and other goods to the prisoners in return for amounts that are several times higher than their market price.

The summon to complete compulsory military service is another source of income. The families of those who are required to complete their military service, pay large sums to transfer their sons to certain military divisions, to fake their son’s papers or even to be able to send their sons outside Syria despite being wanted for military service.

Second Theme: Funding the War for Hayat Tahrir al-Sham

First: Spoils

In his first appearance on Al-Jazeera Channel, Abu Muhammad al-Golani, commander-in-chief of the Hayat (formerly al-Nusra Front ), said they have not received any support from anyone and that most of their funding comes from “spoils” controlled by the Hayat (the Front at that time) and that they accept unconditional funding from businessmen and individuals.

This statement is partly true because Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s (HTS) funding primarily comes from “spoils” taken from battles with the “other” whether the regime, ISIS or opposition factions (see Table 1). In the battle at end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018 with Nur al-Din al-Zanki Movement, HTS adopted a tactic that required splitting the spoil with half going to the fighter and the other half goes to the faction . This approach earned HTS a good participation from of a large number of its fighters and other fighters who joined the HTS in anticipation of these gains. The HTS made advances in several areas.

In the previous battle with Ahrar Sham Movement in mid-2017, HTS took control of Ahrar al-Sham’s entire capabilities estimated at millions of USD. For example, in the city of Salqin alone, north-west Idlib, HTS took control of Ahrar al-Sham’s Khalid bin Walid Camp capabilities. The camp’s vehicles and arms were estimated at 1 million USD . In the same area, HTS seized a media studio equipped with advanced technologies estimated at half a million USD , and seized Ahrar al-Sham car warehouses with an estimated 2000 mostly modern cars valued at more than 20 million USD. HTS took control of Jaysh al-Sunna headquarters, one of the four factions that were running Idlib at that time and a component of Jaysh al-Fatih. HTS also took control of many small factions such as the Islamic Movement whose commander Abu Bakr was killed in HTS prisons. HTS took control of Abu Ali Wishah’s headquarters (he was linked with sheikh figures who received great support), in addition to other operations it carried out in the north of Syria. HTS has acted based on the idea of overcoming that dictates that the winner governs the area and imposes the status quo with the remaining forces present submitting to his rule.

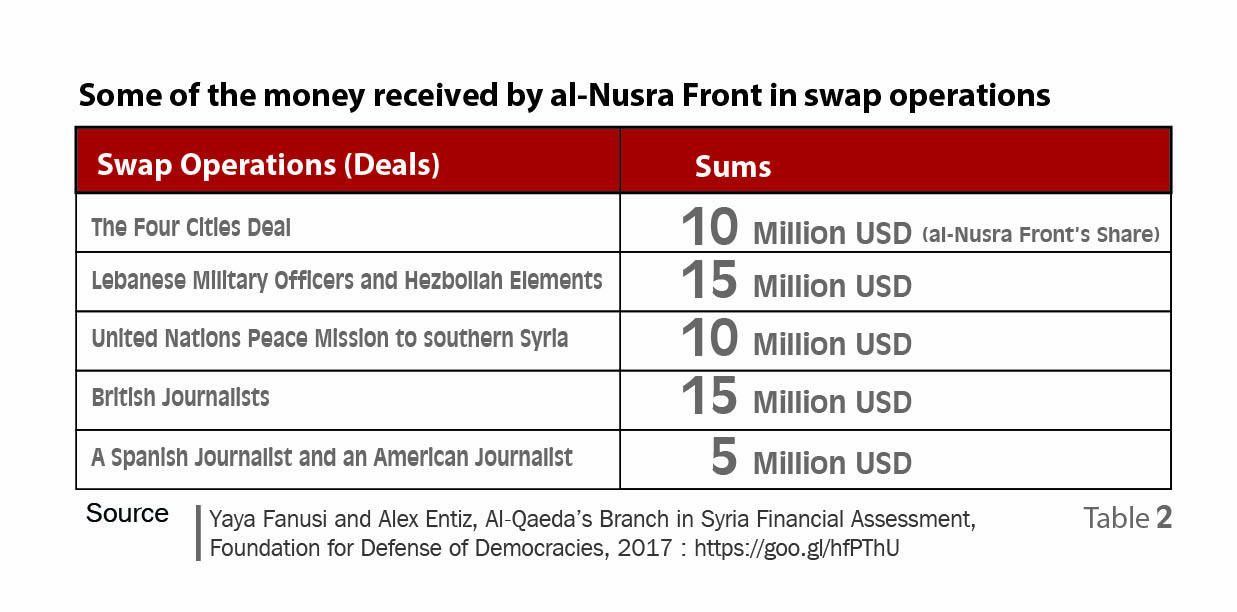

Second: Swap Operations

To secure part of its funding, HTS has relied on swapping captives and bodies (see Table 2). The four cities agreement is considered one of the biggest deals of this kind, and HTS was one of the parties involved. HTS released a Syrian pilot and other regime hostages for which it received large amounts of money estimated at millions of USD, but HTS did not reveal the figure. The Lebanese government paid a large sum, not less than 15 million USD, to HTS to release Lebanese military officers it held hostage. HTS received a similar amount from the Italian Government in the Italian hostage swap operation. In addition to other sums from other exchange operations involving foreign journalists, the bodies of Hezbollah and Iranian fighters, and others.

To secure part of its funding, HTS has relied on swapping captives and bodies (see Table 2). The four cities agreement is considered one of the biggest deals of this kind, and HTS was one of the parties involved. HTS released a Syrian pilot and other regime hostages for which it received large amounts of money estimated at millions of USD, but HTS did not reveal the figure. The Lebanese government paid a large sum, not less than 15 million USD, to HTS to release Lebanese military officers it held hostage. HTS received a similar amount from the Italian Government in the Italian hostage swap operation. In addition to other sums from other exchange operations involving foreign journalists, the bodies of Hezbollah and Iranian fighters, and others.

In all the swap operations, HTS listed the names of Syrian detainees held by the regime or paramilitary forces in return for the release of non-Syrian prisoners. On more than one occasion, the families of the Syrian detainees paid HTS for these operations .

At one point, it became customary for Iran and Hezbollah battalions to pay HTS for each commander’s body around 200,000 USD and for each soldier’s body around 50,000 USD . This was documented in the battles for Aleppo countryside and rural Idlib more than once. In specific cases there have been swaps without the transfer of money, such as swaps where fighters or the bodies of fighters working with HTS were exchanged. HTS is always keen to recover the bodies of those killed among its soldiers, and it seeks to release those soldiers taken hostage.

Third: Factions’ Shares

HTS has made alliances with forces that are not fully subordinate to it. However, it coordinates and participates with these forces in most of the operations such as the Turkestan Party, Jund al-Aqsa and other small factions. These factions are supported by individuals spread throughout the world and sometimes HTS receives part of that support in the framework of merge operations and unification efforts that occur among these various forces.

In addition to alliances, HTS has used the method of direct threats to blackmail factions and obtain financial and in-kind support. In the north, HTS has made agreements with all factions funded by the Joint Operations Room (MOM), whereby it sometimes receives up to 5% of these factions’ revenues in return for not attacking the factions. HTS has eliminated all factions that have not complied with this condition or have manipulated the real figure they receive. In a few instances, HTS obtained other funding sources by organizing campaigns to confiscate the money of gang that worked in northern or even southern Syria. At certain times, HTS confiscated antiquities that men were working to extract from various geographical areas near the Syrian-Turkish border in Sarmada, Kafardiran and Harim Road. In other cases, HTS confiscated quantities of smoke and weapons from persons engaged in smuggling. The confiscated materials are included in HTS general budget.

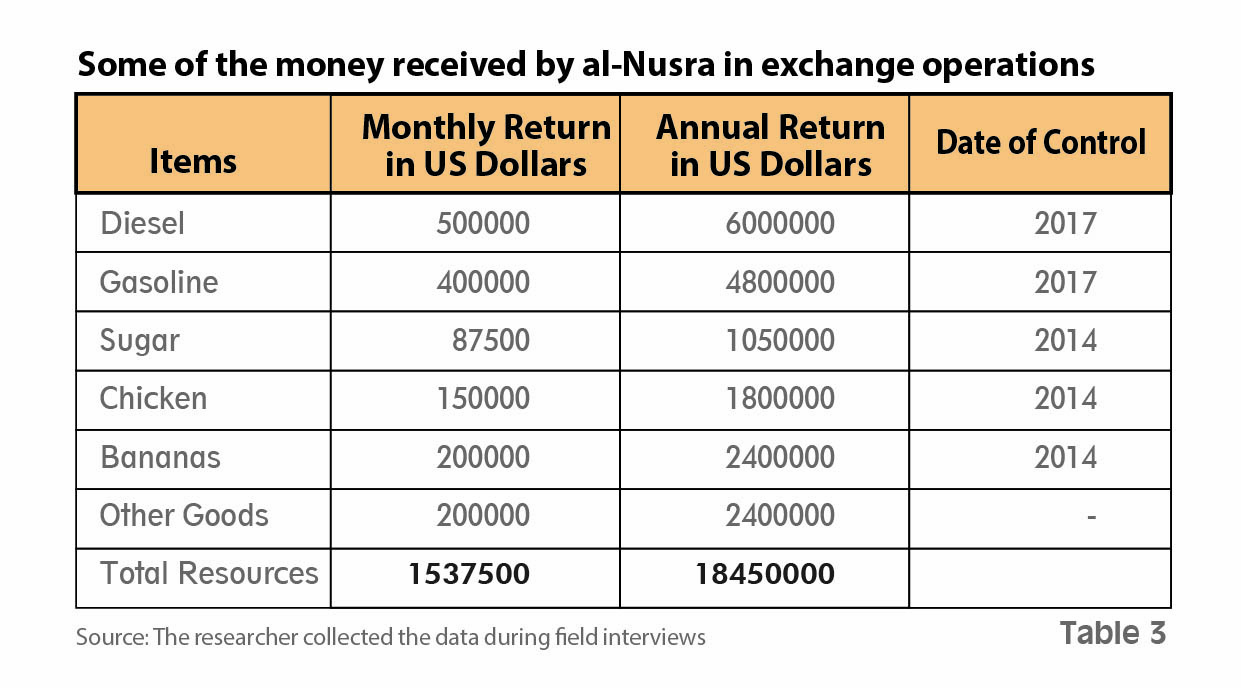

Fourth: Trade and Taxes

All international resolutions and policies have contributed to drying up the funding sources of terrorist-classified groups in Syria , and have drained the external resources that HTS has benefited from. With the near cessation of fighting and the end of most of the factions with which HTS had fought and from which they had received money, the latter turned towards investment operations and business activities in the north of Syria. With HTS taking control of the Bab al-Hawa border crossing, it prevented trading in large quantity of goods except through HTS approved traders . HTS monopolized control over goods such as sugar, chicken, bananas, gasoline and diesel, and a number of other commodities of daily consumption. The Chamber of Commerce was unable to dispute the issue with HTS as HTS often threatened to close down the chamber, and carried out “administrative coup” operations within the chamber more than once. HTS busied the chamber with its internal administrative and organizational issues, so they were unable to take action towards abolishing the HTS’s monopoly.

HTS has also recently moved towards exporting economic frontages in the north of Syria which sponsor small activities. For example, after taking control of Bab al-Hawa Square, HTS established a group of small restaurants as small projects for HTS employees with special cases.

Moreover, HTS operates gas stations and large power generators in exchange for subscription payments. It seized pieces of communal land near the Syrian-Turkish border and began selling it to people to build houses on it.

HTS has border crossings it shares with the regime and imposes fees on the commodities that enter via the crossing. Morek crossing is the most prominent crossing with the regime and HTS share a percentage of the revenues from this crossing with Huras al-Din faction, which previously controlled the crossing before handed it over to HTS for a share of the revenue. In addition, HTS controls Bab al-Hawa crossing .

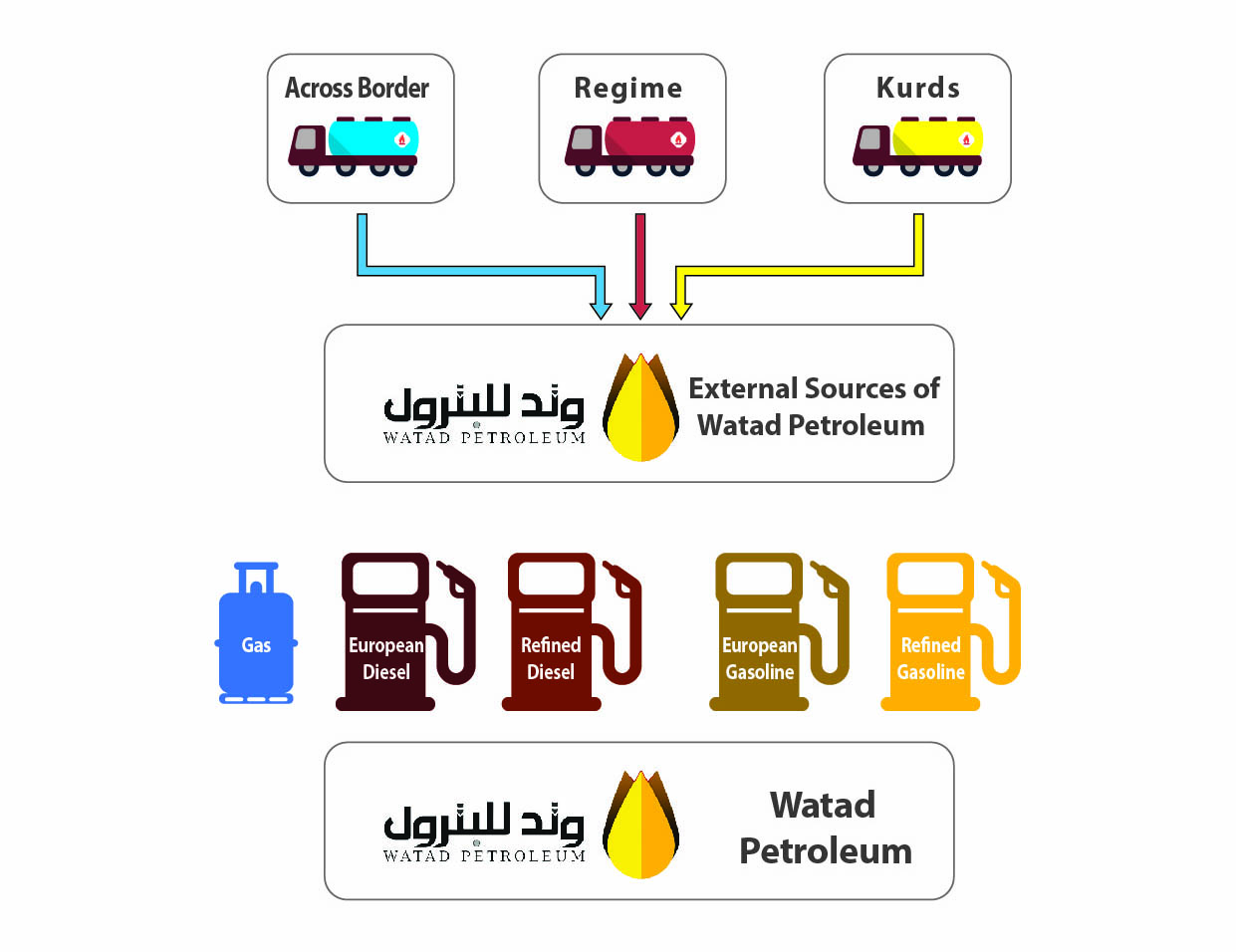

HTS founded Watad Company to manage the fuel in northern Syria. The company claims it is an independent company run by Abu Ragheb al-Nabhan, an old fuel contractor operating in the region.

At one point, it became customary for Iran and Hezbollah battalions to pay HTS for each commander’s body around 200,000 USD and for each soldier’s body around 50,000 USD . This was documented in the battles for Aleppo countryside and rural Idlib more than once. In specific cases there have been swaps without the transfer of money, such as swaps where fighters or the bodies of fighters working with HTS were exchanged. HTS is always keen to recover the bodies of those killed among its soldiers, and it seeks to release those soldiers taken hostage.

Third: Factions’ Shares

HTS has made alliances with forces that are not fully subordinate to it. However, it coordinates and participates with these forces in most of the operations such as the Turkestan Party, Jund al-Aqsa and other small factions. These factions are supported by individuals spread throughout the world and sometimes HTS receives part of that support in the framework of merge operations and unification efforts that occur among these various forces.

In addition to alliances, HTS has used the method of direct threats to blackmail factions and obtain financial and in-kind support. In the north, HTS has made agreements with all factions funded by the Joint Operations Room (MOM), whereby it sometimes receives up to 5% of these factions’ revenues in return for not attacking the factions. HTS has eliminated all factions that have not complied with this condition or have manipulated the real figure they receive. In a few instances, HTS obtained other funding sources by organizing campaigns to confiscate the money of gang that worked in northern or even southern Syria. At certain times, HTS confiscated antiquities that men were working to extract from various geographical areas near the Syrian-Turkish border in Sarmada, Kafardiran and Harim Road. In other cases, HTS confiscated quantities of smoke and weapons from persons engaged in smuggling. The confiscated materials are included in HTS general budget.

Fourth: Trade and Taxes

All international resolutions and policies have contributed to drying up the funding sources of terrorist-classified groups in Syria , and have drained the external resources that HTS has benefited from. With the near cessation of fighting and the end of most of the factions with which HTS had fought and from which they had received money, the latter turned towards investment operations and business activities in the north of Syria. With HTS taking control of the Bab al-Hawa border crossing, it prevented trading in large quantity of goods except through HTS approved traders . HTS monopolized control over goods such as sugar, chicken, bananas, gasoline and diesel, and a number of other commodities of daily consumption. The Chamber of Commerce was unable to dispute the issue with HTS as HTS often threatened to close down the chamber, and carried out “administrative coup” operations within the chamber more than once. HTS busied the chamber with its internal administrative and organizational issues, so they were unable to take action towards abolishing the HTS’s monopoly.

HTS has also recently moved towards exporting economic frontages in the north of Syria which sponsor small activities. For example, after taking control of Bab al-Hawa Square, HTS established a group of small restaurants as small projects for HTS employees with special cases.

Moreover, HTS operates gas stations and large power generators in exchange for subscription payments. It seized pieces of communal land near the Syrian-Turkish border and began selling it to people to build houses on it.

HTS has border crossings it shares with the regime and imposes fees on the commodities that enter via the crossing. Morek crossing is the most prominent crossing with the regime and HTS share a percentage of the revenues from this crossing with Huras al-Din faction, which previously controlled the crossing before handed it over to HTS for a share of the revenue. In addition, HTS controls Bab al-Hawa crossing .

HTS founded Watad Company to manage the fuel in northern Syria. The company claims it is an independent company run by Abu Ragheb al-Nabhan, an old fuel contractor operating in the region.

Third Theme: Funding the War for Opposition Factions

First: Popular Support

During the first period, the popular movement depended on the money of Syrians themselves, Syrians inside or outside Syria. In 2011, the youth of the neighborhood joined together to buy the necessities for the demonstrations. At a later stage, when the killing and arresting of injured demonstrators spread in government hospitals, well-off families started donating to establish field hospitals in their neighborhood while others donated their savings and gold to buy arms.

Funding for the popular movement was not limited to Syrians at home; the diaspora played an active role in raising hundreds of millions of USD, whether to support humanitarian work or field and military operations. In this context, businessmen have made large-scale donations, and some have established special associations to manage this support. The most prominent of these is Dr. Abdul Qader al-Sankari, a UAE-based businessman who founded the Abdul Qader al-Sankari Foundation, which still offers relatively high educational, medical and humanitarian services with relatively large amounts. In addition to Aymen Al-Asfari, based in the United Kingdom and founder of the al-Asfari Chairty Foundation, and Ghassan Abboud, a UAE resident who founded the Orient Foundation for Charity. Other businessmen councils and foundations were also founded.

Public support from inside and outside Syria reached its highest level in 2011, and gradually declined over time. The resources available to individuals were depleted, in parallel with the militarization and division among factions, the expansion of needs and the Syrian scene losing its appeal even among Syrians themselves.

Second: Foreign Support for Opposition Factions

By the beginning of 2013, some countries began to move to secure their interests in Syria. One form these moves were reflected in was countries funding factions or opposition institutions. This form of intervention to support the opposition was through three trajectories:

1. The first trajectory was through supporting specific figures who are known in the public arena

Some countries have directed their support through certain figures, or “endorsing” popular support that is collected from Syrians and others into funds run by these figures. One of the most prominent examples in this trajectory is the cleric Adnan al-Ar'our, a Syrian Salafist living in Saudi Arabia. He had media appearances before 2011 to talk about topics related to the Sunni-Shiite conflict, but in 2011 he turned to the Syrian political issue. He appeared on a daily basis for long hours on a Salafi Channel broadcasted from Saudi Arabia. The regime worked to make al-Ar’our more visible and turned him into a symbol of opposition, and popular demonstrations responded to this as they saw in al-Ar’our a symbol that provokes the regime.

Saudi Arabia has imposed on bodies and associations that collect any funds for Syria inside Saudi Arabia to hand over these funds exclusively to al-Ar’our. Consequently, this turned him into a public figure and he sponsored the formation of “The Joint Command of the Revolutionary Military Councils” in September 2012.

Salafist figures appeared in Egypt and the Gulf states such as Shafi, Hajaj al-Ajami, Zain al-Abidin al-Buqai and others who funded the Salafist scholastic and Salafist jihadist factions with sums amounting to millions of USD on the basis that this money comes from donors. It is not known whether these donors are countries or individuals. Indeed, the size of the funds and the ease of transferring the funds at that time indicated that there was support at a state level or at least the transfers were approved by the state.

On the other hand, Syrian figures such as Amjad al-Bitar played a significant role in supporting opposition groups with money far exceeding his financial capabilities, as it was known of by the people of Homs. Following al-Bitar’s multiple visits to the Gulf countries, most notably his visits to Qatar, Liwa al-Haqq, which was founded in Homs and extended to Qalamoun in the countryside of Damascus and some areas of Idlib countryside, received substantial support from a Qatari businessman known as Abu Rayyan. Zahran Alloush benefited from his previous relations in Saudi Arabia (having studied at Imam Muhammad bin Saud University in Riyadh) and he received support from Saudi sheikhs. Jabhat al-Asala wal Tanmiya (Front of Authenticity and Development) founded by the Ahl al-Athar Brigades also received strong support from the Salafist Madkhali Movement in Saudi Arabia.

Certainly, it is not possible to prove the relationship of any state with providing direct financial support to those figures, but the state may have turned a blind eye or allowed some of its affiliates to pass on the necessary support to control the course of the war in Syria and to secure their interests. For instance, Ahmed Turkawi, a prominent figure in Homs Province, was residing in a Gulf state when he started supporting the first military formation in the city of Homs . With the inflated expenses he was no longer able to secure the necessary funds except through donation campaigns, but the government of the country he was residing in, stopped these campaigns. This in turn finished the faction that he has been supporting and allowed another faction, that it believed to be supported by the same state, to expand.

2. Second trajectory: Direct international funding

International support publicly appeared in the post-2014 phase by providing trainings for combatants, supporting medical and media work and providing some sums to set up food kitchens for fighters. Later, international funding developed to support the establishment of the joint operation rooms such as MOC in Jordan and MOM in Turkey by giving non-fixed salaries to nearly 50 military factions in the south and north of Syria. The most prominent of these factions were the military councils in Daraa, Sham Legion in the north, the Army of the Mujahideen, Fastaqim Group and others .

The majority of the factions in the north that received support from the MOM Room used to provide a percentage of the sums and weapons they received to HTS in exchange for HTS refraining from targeting them. HTS eliminated all the factions that refrained from providing this percentage or worked to circumvent the payment.

The funding for the joint operations rooms was stopped completely in July 2017. After that, the Euphrates Shields factions were sponsored directly by Turkey where the factions receive monthly allowances deducted from the revenues collected from border crossing movement in the Euphrates Shield area.

In addition to the operation rooms, some countries provided direct financial support to specific factions. The support was provided in cash and delivered by hand (in Turkey and Jordan) by direct representatives of the supporting countries. Some supporting countries continued to provide direct support even after the establishment of the joint operation rooms, leading to disputes within the rooms as this funding was considered a distraction from the objectives for which the rooms were created.

3. Third trajectory: Technical and logistical support

Opposition factions received logistical and military assistance from the International Alliance or Turkey in the framework of supporting the war against ISIS. In some cases, factions also received set financial sums during their military operations against ISIS. The most prominent cases of this assistance were in the battle of Kobani in late 2014, during the battle in areas that later became known as the “Euphrates Shield” areas in mid-2016 and within the framework of the Olive Branch Operation in early 2018.

Ahmad al-Abdu faction in south-east Syria received extensive support to fight ISIS as the USA backed the faction in several battles on more than one occasion. Also, British forces coordinated with the Authenticity and Development Front forces to carry out small operations against ISIS near Deir Ez Zor including parachuting operations to arrest persons wanted by Brittan.

Third: Spoils and Ransoms

As of the second half of 2011, opposition factions were able to take spoils from regime checkpoints, centers and other institutions. Defected army members also began bringing whatever light and heavy weapons they could bring.

Since 2012, the armed opposition started to obtain financial resources in exchange for releasing foreign detainees. At the beginning of 2012, the Farouq Brigades detained some Iranian officers and received a sum of 5 million USD to release them . In October 2013, according to some sources, The Northern Storm Brigade received an estimated sum of tens of millions USD in exchange for releasing some Iranian nationals they had detained in Aleppo countryside. Other cases where opposition factions were able to obtain large sums in exchange for releasing detainees and captives have been documented.

Fourth: Trade and Investments

With the expansion of the battles and due to the conditionality that accompanied most of the funds received by the opposition factions in recent years, some voices have called for the independence of the opposition support. They suggested ideas such as investment, trade and reactivating popular support that has been exhausted as a result of the long years of war. This pushed the majority of factions to search for high income investment and trade processes. Major formations began to develop what is known as an economic unit, known in abbreviation as “economic”. The economic unit is responsible for two main tasks:

1. First: Developing the formation or movement’s resources and trying to “evade” conditional support.

2. Second: Carry out projects to improve the faction or formation’s image in the area they are based in.

The most prominent economic units among the opposition factions was the Ahrar al-Sham Movement’s “economic” which managed a series of restaurants and kitchens, car import stores, spare parts stores, agricultural projects and small workshops. In addition, Ahrar al-Sham’s economic unit invested in real estate. It built commercial properties near Bab al-Hawa and leased them to organizations wishing to work in the region for relatively good sums. An office area estimated at around 100 m2 can be bought for 40,000 USD and renting an office cost in excess of 250 USD per month. The economic unit also imported hundreds of Kia Certo model cars, which are in demand in the north of Syria. The prince of one of these cars reaches around 15,000 USD.

HTS confiscated most of these cars in their recent battles with Ahrar al-Sham Movement and then sold the cars through offices that they deal with or which HTS open just for this matter.

Likewise, in Eastern Ghouta, Jaysh al-Islam opened a large arms shop and ran small projects. However, the size of arms trade in the Jaysh remained limited and did not take off as was the case in the north of Syria due to the siege and the escalating confrontation with the regime.

The Rahman Corps founded the “Rahma Trading Establishment” which specialized in selling the main commodities needed by the people of rural Damascus, but the institution’s revenues were not large.

For a long time, the Levant Front maintained its funding by controlling the Bab al-Salama border crossing with Turkey and imposing taxes on imports. In western Aleppo countryside, the Nur al-Din al-Zanki Movement imposed taxes on shipments moving through areas under its control. The Movement was able to collect good sums that enabled it to withstand for a long time the scarcity of financial support.

Some of the opposition factions seized properties in Aleppo, the villages of Hama and Idlib from many people, either on the pretext of that these people were dealing with the regime or that they were members of ISIS. Part of the factories in the industrial zones in Aleppo were dismantled and sold in Iraq or Turkey or in the north of Syria itself. On the Syrian-Turkish border, border crossers can see the remains of machines and spare parts which were transported from Aleppo. Some businessmen were forced to pay sums to other factions to protect their property which was considered an acceptable source of income during the period of protection.

All the factions, together with all the other actors in Syria, have been involved in the transport and smuggling trade, including the transportation of goods, people and funds from one area of control to another. These activities will be discussed in detail in the second chapter of this study.

Fifth: Current Situation of the funding for Opposition Factions

We can divide the support for the factions into three main stages:

• The first phase depended on widespread popular donations from inside and outside Syria, and accessing weapons through dissident individuals or from army checkpoints and military blocks that the factions took control of. These factors ensured these factions strengthened their stature and spread to most areas in Syria. This stage began with the formation of the brigades in late 2011 until the beginning of 2013, so for over a year.

• The second phase during which the majority of factions depended on donors, who are predominantly linked to countries in the region. The donors supported factions directly or support via coordination rooms. This phase secured factions almost stable monthly support, enabling them to expand the number of fighters and to launch major battles. On the other hand, it influenced the nature of factions’ decisions.

• The third phase, during which some factions moved towards relying on self-funding by establishing projects, but these were insufficient to cover the inflated expenses that had developed during the external support stage. After Russia and the regime took control of most of the opposition-controlled areas in Syria, the majority of opposition factions are limited to northern Syria.

The last stage is considered the most difficult for the factions in terms of the availability of resources. Most of the individual donors stopped providing support either because these factions lost the area they were controlling or due to legal restrictions on the money transfer which makes these individuals accountable in their countries of residence. All countries have suspended their supported for the military opposition, including Turkey. In the last six months, Turkey only paid a small amount of money to the brigades that participated in the Euphrates Shield and the Olive Branch operations. For example, the Sham Legion is considered the faction most capable of mobilizing to secure support; however, its fighters received salaries on average once every two months and in amounts not exceeding 25 USD over the past six months. The remaining Ahrar al-Sham fighters receive less than 10,000 Syrian Pounds (SP), around 20 USD per month. Most of the currently operating factions are still able to secure the minimum necessary to sustain themselves through their relations with Syrian donors and traders who support them.

Fourth Theme: Funding the War for ISIS and Kurdish Autonomous Administration

First: ISIS Funding Resources

ISIS’s resources reached its peak between 2014 and 2015, where its annual revenue reached an estimated 2.2 billion USD making it the richest terrorist organization in world history .

1. Oil: Oil is one of ISIS’s most important financial sources. At its peak, ISIS’s daily production was estimated at around 50,000 barrels whereby ISIS’s monthly revenue from oil reached around 50 million USD . In all cases, oil revenues accounted for the bulk of the organization’s budget.

The coordination related to the extraction and sale of gas and oil represented an important form of cooperation between the regime and ISIS, and a fundamental source of funding for ISIS. One of the most prominent agreements occurred after ISIS took control of the Conoco gas extraction plant east of Deir Ez Zor on May 09, 2014. An agreement was reached between the regime and ISIS for the plant to be operated by engineers subordinate to the regime and in return, ISIS received a share of the regime factory’s outputs, as well as providing gas for the Sana station in the Ghouta area and the Jandar station in Homs.

After ISIS took control of the Twayin oil field south of al-Tabqa in April 2014, the regime and ISIS reached an agreement whereby the regime sent its engineers and staff to operate and maintain the plant and in return, ISIS would protect the factory and ensure the safety of the engineers. The resources were divided between the two parties whereby the regime receives 60% of these revenues and ISIS the remaining percentage.

2. Spoils of war: Spoils represented a major part of ISIS’s resources as is the case with HTS and other opposition factions. However, ISIS expanded significantly in this domain as it expanded the concept of ‘Takfir’ for it to include practically all those opposing ISIS. When ISIS took control of a town, area or city, its forces would immediate begin “gathering spoils” which included everything from sheep and cows to precious household items, money, merchandise, cars and homes.

In Iraq, ISIS obtained a unique set of spoils represented in its forces seizing the content of (121) branches of state and commercial banks including the branch of the Central Bank in Mosul. According to the estimations of the Iraqi Central Bank, ISIS seized a total of more than 100 million USD and over 850 billion Iraqi Dinars .

3. The Zakat Bureau: The Zakat Bureau is considered one of the most important non-oil sources of revenue for ISIS. ISIS used force to make all those residing within its territory, from traders and ordinary individuals, to pay 2.5% of their money as zakat. The receipt from the Zakat Bureau demonstrating the payment was made became a highly effective document to pass ISIS check points.

4. The Sale of Antiquities: ISIS used the antiquities in Iraq and Syria in a double manner. They issued recordings showing ISIS forces destroying the large antiquities that could not be sold to gain an audience among those who hate civilization in general. They then sold small pieces that could be smuggled. ISIS exploited the images and videos showing the complete destruction of archeological sites to conceal the organized thefts. It is estimated that the Iraqi and Syrian antiquities that ISIS sold are valued at over 200 million USD .

5. Agriculture and Trade: ISIS invested heavily in agricultural land and water resources. The organization has worked to sell agricultural products to a number of actors, the most important of which is the Syrian regime. Hossam Qatarji (a current member of the Syrian People's Assembly) played a major role in buying wheat for the Syrian regime .

6. Transit fees: ISIS, like all the other actors, imposed taxes on the passage of vehicles and persons from its areas to all other areas.

Second: Funding Resources for Kurdish Autonomous Administration

1. Agricultural and natural resources: The Democratic Union Party (PYD) control the territory that is considered one of the richest regions in Syria as it includes several oil and gas fields as well as large agricultural resources.

The PYD worked to export oil on the black market in similar manner to ISIS. During the period 2014-2016, PYD and ISIS controlled most of the oil and gas fields in Syria. The regime is the PYD’s number one customer for its oil products, but the regime exploits the situation to obtain prices well below the market value.

2. External Support: The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) of the Kurdish administration receive direct military support from the USA and its allies. Washington says the support it provides is limited to equipment necessary for the war against ISIS and that it closely monitors this support .

The International Coalition provides tens of millions of USD to the SDF which is only sufficient to cover the salaries of its members according to the Coalition.

The US was allocating 200 million USD for what it describes as stabilization projects in areas east of the Euphrates. This money was spent on water, sanitation, education, health, road networks and rubble removal projects. President Trump decided to discontinue this funding on April 31, 2018 . Saudi Arabia has allocated 100 million USD to these projects and delivered the amount to the USA on November17, 2018 .

3. Fees and Taxes: The Autonomous Administration collects taxes and administers based on a quasi-governmental system in all the areas under its control. The system includes collecting fees and taxes on services rendered, such as the registration of cars and real estate, transit tax on cars, people and merchandise. For example, the Autonomous Administration charges an annual fee of 300 USD for each car registered and 5 USD for each person transiting through its territory. It charges cars carrying goods or fuel fees based on the goods whereby the average fee is an estimated 10 USD per ton. The Autonomous Administration also levy taxes on shops and real estate.

Second Chapter: Inter-trade Relations between the Conflicting Forces in Syria

First Theme: The Roots of Economic Inter-relations between the Conflicting Forces

Trade between warring parties is not unique to the Syrian case. During the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990), trade relations emerged between the warring factions. The Lebanese village of Deir al-Qamar (located between Beirut and Sidon) was besieged in the 1980s, and various companies and individuals loyal to different factions brought fuel and food products into the village for large sums of money. Also, from 1985 to 1987, thousands of Palestinian fighters were brought into Lebanon through Jounieh airport which was controlled by the Lebanese Forces. Although the Lebanese Forces, already already opposed the Palestinians, the fighters entered in exchange for large amounts of money and for them to fight the Amal Movement militia which was considered the Lebanese Forces’ enemy at that time . The events of the Lebanese civil war offer many examples of trade relations that paved the way for Lebanon’s current economy in which former war powers or powers that emerged as a result of the war control the state public facilities and codified the war economy built along the civil war lines of conflict.

In the case of Yemen, commercial exchanges between the conflicting parties are considered an issue of activity and effectiveness throughout Yemen. Control of the Hodeidah port and its management has played and continues to play a major role in the conflict. The port is the main entry point for Yemen’s imports. The conflicting parties set up military checkpoints that charge fees to allow trucks to pass . The Houthis have established private oil and gas companies, through close traders, which sell oil and gas in different areas to fund the Houthi war activities. In the capital, which is controlled, so far, by the Yemeni forces, Saudi products are visible in shop shelves, including Saudi milk, which means it arrives fresh almost daily.

First: Intertwined Needs and Greed

The Syrian regime structure is focused politically and economically on the premise of “loyalty in exchange for authority”. Based on this rule, thousands of officers and officials in the al-Assad regime have managed to accumulate massive fortunes in return for their loyalty. With the start of popular protests against the regime, the regime expanded this rule to include confiscation of property and blackmail of those accused of opposing the regime. This served as a tool to punish people and areas on the one hand, and finance the security personnel and auxiliary forces on the other.

On the other side, opponents of the regime relied on the so-called “internal agent” whereby persons in regime areas collaborated with the opposition for intellectual or economic reasons. These people paid for the purchase or transit of ammunition, personnel or medical supplies required by the opposition.

The Kurdish administration was the most “pragmatic” among all actors in terms of building political relations alongside economic relations. It maintained the regime presence at a minimum, ensuring that it obtained the necessary official documents and international legitimacy as well as the economic resources provided by trading with the regime.

The inter-relations among the various actors resulted in the emergence of “war merchants”, who acted as cross-border mediators between the conflicting parties. They formed networks of relationships that enabled them to protect their businesses during a fierce war and enabled them to build large and sometimes excessive fortunes.

Second: Sharing Land and Resources

The nature of the distribution of land control in Syria played a role in the economic relations. The regime sought to preserve what was known as the “useful Syria” which in one way or another enabled the regime to control the state centers and the civil dimension in Syria; however, the regime’s areas were not “useful” in terms of natural resources such as oil, gas, water and agricultural land, which are located in the eastern region starting from Homs’ eastern countryside (Palmyra and al-Farqalis) to the north-eastern corner of Syria. Over the past five years, these areas have been divided between ISIS and the Kurdish Autonomous Administration.

Although the regime, after being an exclusive owner, became a customer seeking these resources from the actors who controlled them, it searched in a limited manner for external sources. This was also observed for other actors in the conflict due to two basic considerations:

• Low prices: The regime obtained oil products sometimes at prices less than a quarter of the oil products’ value in the global market. ISIS was selling the regime one oil barrel for around 20 USD while the average international price of a barrel in 2013 was around 91 USD, and in 2014 it was around 85 USD.

• Low cost of transport: which gives the goods and products coming from other areas in the conflict in Syria a competitive advantage in local markets. This allowed for the political, and even security and military, risks of dealing with the other parties to be overcome.

In recent years, all the areas of influence have enjoyed certain competitive advantages that allowed them to not collapse economically at least, even if their natural resources are somewhat limited.

Third: Trade as an Entry to Subsequent Understandings

The various parties used their economic relations in certain cases to build transient economic understandings. For example, in the case of the Abu Dali crossing in the north-eastern countryside of Hama which separates the regime and HTS, there was a “free zone” between the two side (the area of Abu Dali itself). For years, the Abu Dali area has been the most prominent commercial and transportation area in Syria. The Ahmed Darwish Group, a group independent from the regime, HTS and the opposition, governed the area. Although the group had a pro-opposition regionalist stance and strict practices similar to those of HTS, they also had privileged relations with the regime through Ahmed Darwish who became a member of the Syrian People’s Assembly in the 2012 term.

HTS used to obtain all its economic resources through this region, including some types of weapons, and the regime obtained food and cheap clothing from Turkey. In return, it ensured that HTS would not attack the Khanser of Aleppo road which is considered an essential road for the regime due to the closure of other roads. The village of Abu Dali is located directly on the road, and the regime does not enter it. The village has all the main services such as electricity, water and communication lines (unlike the opposition areas). HTS can get everything it asks for via the village, including electricity for some opposition villages close to Abu Dali. This created a type of understanding where political military and economic factors merged; however, at a certain point when this balance was broken, HTS stormed the village of Abu Dali. The move came after HTS had benefited from the village for three whole years. HTS expelled the Ahmed Darwish forces and in return, the regime closed down the crossing point. The regime had by that point, secured other roads that it could use to reach Aleppo after it expelled the ISIS forces from the eastern area .

In another case, regime forces in the al-Waer neighborhood in Homs were stationed in the “Al-Bar Hospital for Social Services” which is located on the outskirts of the opposition-controlled neighborhood. The opposition forces could have targeted the regime fighters during the change in watch shifts or even arrested them at any time. This did not happen until the opposition forces exited the neighborhood as the regime elements would supply the opposition forces with car batteries and fuel needed for the electrical generators and sometimes communication devices in exchange for protection from opposition factions.

The Kurds present in the Afrin region had good trade relations with the opposition forces. They allowed everything to enter the western and eastern countryside of Aleppo, including gasoline, olive oil, vegetables and other products coming from nearby areas. They knew that not allowing these products to pass would result in their military isolation in between two opposition areas. At the time of the Olive Branch Operation, the end of this agreement resulted in the increase in the price of fuel across Idlib. The siege by all sides resulted in the area of Afrin falling in the hands of the Free Syrian Army and the Turkish forces supporting them. Trade was then an entry into understanding and a chess piece that the different sides benefited from at the right time.

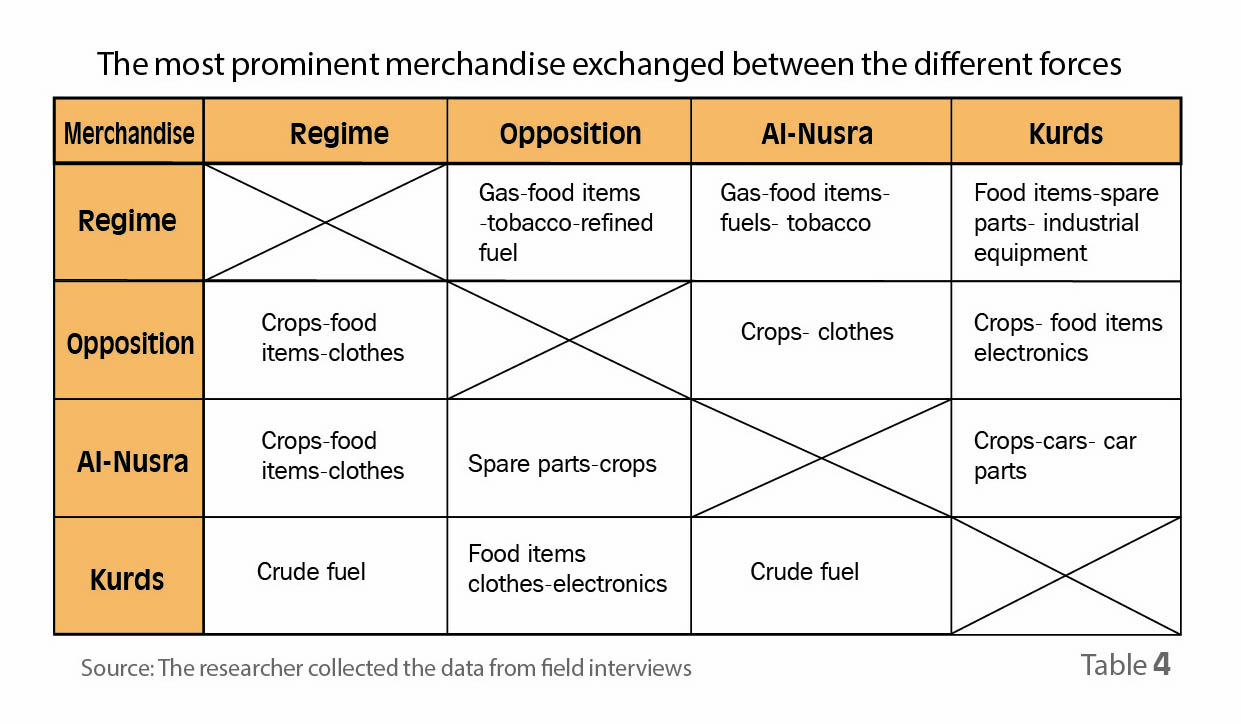

Second Theme: Merchandise Trade and Services

First: Flow of Commodities and Services

As the conflict in Syria approached its 8th year, the flow of goods and services played a vital role in the Syrian war. Sometimes the flow of goods formed an area of understanding and at other times it was the determining factor. The regime cut off the supply of goods and services to various areas, most notably Old Homs, al-Muadamiye, Daraya, Eastern Ghouta, al-Yarmouk Camp and other areas. In the case of Old Homs, the regime managed to maintain cutting off supply for about 700 consecutive days, which resulted in cases of malnutrition in the besieged area, and finally pushed the opposition factions to reach an agreement with the regime to exit the area towards another area.

Al-Waer neighborhood in Homs Province and Barzeh district in the heart of Damascus were two unique areas in terms of the trade relations between the opposition and the regime. The regime allowed the flow of goods and services during the negotiation period when sessions were held between the two parties. The regime allowed entry of small amounts of perishable goods (such as vegetables, milk and meat) that would suffice for a few days, so that residents or opposition forces could not store them especially in the absence of electrical power. In return, the opposition forces allowed the regime to operate its vital facilities in the vicinity of this area. In Barzeh, employees of the Scientific Researches Center and nearby facilities used to enter and exit the area under the watchful eyes of the opposition forces, and nearby vital roads functioned as usual. In al-Waer, the Homs refinery (on the edge of the western al-Waer neighborhood) and the vital Damascus-Tartous road functioned well. Sometimes these facilities were disrupted for a few days due to disputes between the two parties, and then return to work following a new agreement.

In Eastern Ghouta, trade relations between the regime and the opposition were carried out by Muhi al-Din al-Nafosh (Abu Ayman), a businessman who runs a factory producing animal derived products (cheeses, milk, meat, etc.) which are indispensable products for Damascus. Despite the regime besieging the Ghouta area, these materials entered Damascus from Eastern Ghouta. In return, the opposition areas received small quantities of food items that were usually sold for twenty times higher than their real price.

The tunnels, which the opposition factions dug, connected opposition-controlled areas with the outside. The tunnels were large enough to accommodate cars. These tunnels were used to export agricultural products to the opposition areas and to import almost all goods from regime-controlled areas, thereby providing the factions in power and especially Jaysh al-Islam with huge financial resources.

Hundreds of goods continue to flow into Idlib and Aleppo countryside which are controlled by the opposition forces and HTS via regime-controlled land. The goods are transported through the Morek and al-Madiq crossings as the formerly used Abu Dali crossing was closed after the HTS attack, and as an alternative the Morek Crossing was directly opened. The most significant goods entering Idlib and Aleppo countryside are Syrian food products, gas cylinders, imported car parts and vegetables and fruits.

On the other hand, the roads between opposition areas and Kurdish autonomous region have never been cut off (except during the Olive Branch battle in which the roads with Afrin, only, were cut off for three months). Merchandise and people continue to move from and into Manbij towards the opposition-controlled Euphrates Shield area. The most prominent item that enters the area is fuel and the items that exit are clothing, food and electronics. The size of Turkish products and Syrian goods manufactured in regime areas can easily be noticed in the markets in the Kurdish regions. These are products that mostly come from the crossings with the opposition and the regime, whereas Iraqi Kurdistan handles the entry of the remaining Turkish products.

Second: Oil and Gas

The flow of energy sources formed a pivotal point in the search for economic relations among the various parties. The party controlling the oil in Syria controls the most important part of the wealth. ISIS controlled the oil and gas for years and during those years it imposed trade relations with all parties in the form it desired. Today, the Kurdish Autonomous Administration controls most of these resources and imposes its own equations on all parties.

Today, oil in its raw form is the most important commodity exported from Kurdish Autonomous Administration regions to regime, opposition and HTS-controlled areas. The regime can exploit the oil more than the remaining actors because it has two main refineries, namely, Homs and Baniyas refinery in addition to packaged gas.

HTS, the opposition and the Kurdish Autonomous Administration have private refineries that are primitive in manufacturing. However, these refineries enable them to exploit crude oil and convert it into three main products: diesel, gasoline and kerosene. These refineries have developed significantly over the years to produce economic and cleaner types of these products. In the north eastern countryside of Aleppo, (the Euphrates Shield region) controlled by the opposition, these refineries are widespread and operate in a highly efficient manner and their oil products are sold at relatively good prices to the remaining areas.

Third: Crossings and Re-supplying

The re-supply of import goods is a vital and important issue for all parties. All parties have crossings with the surrounding countries. The Kurdish Autonomous Administration has a border crossing with Iraq, the opposition and HTS currently have border crossings with Turkey (previously they had with Jordan) and the regime has crossings with Lebanon as well as air and sea crossings with the rest of the world.

For years, HTS and the opposition have been supplying the Kurdish Autonomous Administration region with automobiles (small cars, minibuses, small and large trucks), and until this point, the Kurdish Autonomous Administration region continue to receive a large part of their automobile needs and vehicle parts from these areas. These cars are imported for these areas through the opposition and HTS border crossings with Turkey. The Kurdish Autonomous Administration areas are also supplied with different electronic items such as laptops, clocks and other objects. In turn, the opposition and HTS obtain mobile phones and accessories which are often obtained through the Kurdish Autonomous Administration’s relations with Iraq or the regime.

Regime-controlled areas receive various materials coming from Turkey or China such as food items, clothing and textiles. In some cases, the exporter to regime areas is forced to change the phrase “Made in Turkey” because the phrase might cause the exporter problems with regime apparatuses . Turkish food products and clothes are considered competitive goods in Syria in terms of quality and price. In addition, a large number of Syrian factories have moved to work in Turkey after 2011 and these factories still have customers in various parts of Syrian and supply them with products.

In the same way, Russian goods also sometimes enter to opposition areas. In a remarkable development - the first of its kind – in mid-2018, three trucks carrying Russian goods entered through the Bab al-Hawa crossing. It should be noted that Ukrainian goods also entered opposition and regime areas and it seems that the issue of re-supply will develop in the future to form part of the understandings of the countries that control the current Syrian scene.

Third Theme: Financial and Monetary Relations

First: Transferring Funds and Clearing Operations

Commercial transactions cannot be carried out without transfer of funds and hence we find that all parties used third parties to carry out the clearing and transfer of money processes. The regime relied on businessmen close to it such as Nader al-Qalai who works freely through Lebanon's markets and banks. The Kurdish Autonomous Administration, ISIS and HTS worked to transfer their money to outside of Syria through figures close to them.

The different parties need to transfer funds when dealing with parties outside Syria. Inside Syria, the transaction is carried out through direct cash payments or through exchanges. In HTS and ISIS deals, oil tanks used to exit HTS-controlled areas loaded with pure gasoline and return with crude oil. In both cases, the payment processes take place directly at the checkpoint and even before unloading the cargo; therefore, all parties did not face liquidity problems and they are often paid in advance as a factor of confidence.

In many cases, financial issues were processed t through clearing operations, i.e., after a series of input and output operations; calculating what has entered and exited and identifying the debtor and the creditor. Consequently, the payment process is ultimately done on the chain of transactions. These cases often take place among a group of traders and on the basis of prior knowledge, which facilitates the transfer and carrying of funds.

For this purpose (and for other purposes, of course), ISIS established what is known as a public relations officer position, an idea that some of the opposition factions and HTS replicated. ISIS appointed a person with a good reputation as a public relations officer in the trade zone. This person secures all trade process through his reputation, which often comes either because of his position in his tribe or family or because of his trade experience.

In besieged areas, the need for money was minimal and hence money was handled through an external network of relationships. The besieged people needed goods and not the money itself, and these goods came from outside the besieged area. Every besieged area has established its own external clearing networks to run its business.

The clearing networks of besieged areas used to receive external donations sent to these areas, whereby the network receives and distributes donations according to the terms of payment determined by the person who runs the network from inside the besieged areas.

Second: Money and Exchange Rate

With the development of the conflict in Syria, the warring forces became different in terms of the currencies each uses; for instance, ISIS minted its own money from gold and silver. This step was more for media purposes than practicality as no one outside ISIS-controlled areas accepts this money. There was no acceptance of this currency in HTS, opposition, regime or in Kurdish autonomous controlled areas despite the fact the money is made of gold. However, after the battle of Raqqa, the gold coin was widely put up for sale in Kurdish autonomous areas, HTS and the opposition areas. The coins were melted for re-manufacturing as gold, but in ISIS-controlled areas, the coins were used for all monetary transactions.

In opposition-controlled areas (Olive Branch and Euphrates Shield), most of the daily dealings are carried out in Turkish Lira and Syrian Pounds. In HTS-controlled areas, US Dollars dominate the scene. However, after Turkey enforced the transfer law through the postal office, the Turkish Lira started to control a wider range of transactions. The regime imposes dealing with the Syrian Pound, but the pricing is set in US Dollars, meaning that the value of goods changes on a daily basis with the appreciation or devaluation of the Pound against the Dollar.

The Central Bank of Syria has tried for many years to dominate and control the market and it has failed many times. HTS has established what resembles a central bank to control its monetary assets and ensure that their value does not fall. Despite HTS’s use of experts in this regard, it has failed more than once to secure its interests. At the end of 2017, HTS tried to maintain a low price for the Syrian Pound (after it became 1 USD to 400 SP), where the price dropped from 500 to 400 Syrian Pounds. As a result, HTS raided money exchange houses and arrested money exchangers in the north of Syria, accusing them of dealing with the regime, and HTS “monetary policy experts” could not deal with this matter. On the other hand, Duraid Durgam (the governor of the regime Central Bank) emerged smiling over this victory achieved by holding commercial transfers of Syrian traders for long periods of more than three months. As a result, accusations were circulated that the Central Bank of Syria had stolen these funds.