Why has Syria Added Graduate Retiree Officers to its Reserves?

On December 11, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad issued a law requiring retired officers with a university degree- doctorate, master’s and bachelor’s - to report for service in the country’s reserves whenever necessary, depending on the needs of the armed forces and the advice of the Officers’ Committee. The requirement can be extended on an annual basis until the officers reach the age of 70, and the law does not specify the age at which someone can be delisted.

Known as law Number 28, it is part of a package of recent legislation reflecting further structural changes within regime forces. The drive for these changes likely comes from Russia, as it does not appear that the decisions and laws being announced are actually being implemented on the ground.

Moscow appears to want to benefit from the experience of retired, graduate officers in missions both inside and possibly outside Syria, in a way that supports a process currently underway to reorganize regime forces, including by dissolving and integrating certain divisions. While university graduates constitute a very small percentage of the total number of regime officers, they are important to Russia. The majority of them graduated from Russian military academies, with various specializations, and they are complimentary to younger regime military personnel who have also been trained by Russian military police or specialized Russian army trainers.

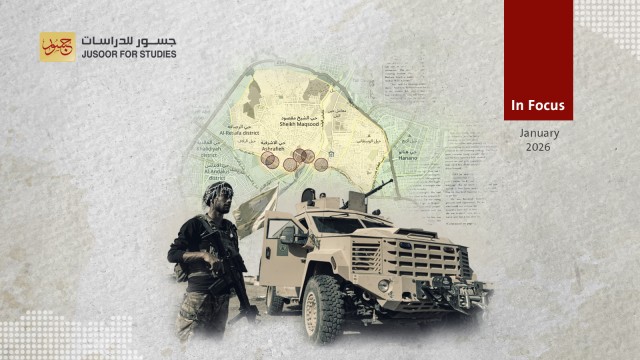

The regime has also made several moves to reconstitute forces depleted by years of conflict with armed opposition groups. It has dissolved the training branch of its Military Security agency, integrating its officers into the Palestine Branch. It has also merged other divisions affected by major casualties and material losses throughout the war, such as the Fifth and 15 th divisions in southern Syria. Through these changes, the regime is trying to show that it is responding to its “re-normalization” with the Arab world by making progress on the political, military and security levels, preparing the way for the return of Syrian refugees and the release of detainees.

The changes also reflect expanding Russian control over the military in Syria, which is now divided into three sections. The first is made up of security and military units that answer directly to the Syrian regime. Russia is making efforts to impose its control over these units by using its trainers to supervise their general activities, as well as their training and education programs.

These forces may be seen as auxiliary forces to a second section, which Russia has directly “adopted” through support with training and arms, as well as assigning tasks and granting monthly salaries. These units include the 25 th Special Mission Division led by Suhayl al-Hasan.

In the third category are Iranian militias, which are making efforts to recruit Syrian fighters, and which leverage their advanced relationship with certain units, especially the Fourth Division, as a cover for their deployment. Both Russia and Iran leverage the deployment of these military units across wide geographical areas by training their personnel.

These changes appear to represent a new restructuring of the regime’s military and security services. They follow a logic that is consistent with protecting Russia’s interests and promoting its influence in Syria. They are also taking place in the absence of any constitutional or legal reform that would define the powers of the military and security services or lift the legal immunity they currently enjoy. Military field courts have already been abolished, although their powers have remained, in the hands of other institutions.