The Economy of the Syrian Regime: Approaches and Policies 1970-2024

Introduction

In theory, the Syrian economy was has been organized along socialist lines ever since the Arab Socialist Baath Party took power. In the 1969 constitution issued in the early years of its rule, the party stipulated that the country would be run according to a “planned socialist” system. This characterization remained in place for decades, until 2012, when a new constitution removed the theoretical label of socialism—although the regime continued to implement some socialist economic policies in a selective manner. The 2012 constitution did not specify the nature of the economy, but defined it as a national system based on the development of both public and private economic activity, aimed at meeting the basic needs of society and individuals, and achieving social justice and sustainable development.

In practice, Hafez al-Assad’s policies were not of a hardline socialist character. The radical socialist measures that were carried out—nationalization, land reform, social security, provision of free health and education services, and expansion of the productive public sector—largely took place during the Baathist rule of his predecessor Salah Jadid, who was in office from 1963 until his overthrow in 1970. The new Assad regime followed some ostensibly socialist policies, such as job creation in the public sector to absorb and co-opt human resources, while gradually adopting certain quasi-liberal measures, notably to serve the interests of the bourgeoisie of major cities such as the capital Damascus. These policies culminated in the 1990 Investment Law, which fueled an accumulation of wealth by figures affiliated with the regime. [1]

In 2005, a few years into the rule of Assad’s son Bashar, the Baath Party’s national congress approved the transition to a “social market economy.” The stated goal of this was to engage the private sector in Syria’s economic development, but the real agenda was to accumulate more wealth in the hands of regime loyalists, through foreign investment. This exacerbated social and economic problems and chipped away at the middle classes. Meanwhile, sustainable development plans were never completed, and social justice was markedly absent.

This demonstrates the broader point that Syria lacks a clearly defined socio-economic system. That is to say, it operates neither on a model that can truly be called socialism, nor one that is clearly capitalist. Contrary to his claims of following a system of absolute, planned socialism, Hafez al-Assad focused on socialism as a slogan rather than a practice. His son’s regime shifted to the “social market” model to give more powers to pro-regime businessmen and more space to his key backers to operate freely and accumulate wealth.

After 2011, the regime took a series of measures that mixed socialist and capitalist principles, despite the Baath Party having defined the country’s economy as a social market system. It began applying these measures without regard to the constitution, which enshrined a form of planned socialism; instead, the government tended towards a social market economy. Moreover, since 2020, Bashar al-Assad has nudged the country towards an economic model similar to the Chinese system of so-called “state capitalism.” [2]

1. The Syrian Regime’s Approach to the Economy

When Hafez al-Assad came to power, he did not adopt a specific economic approach. Rather, he adhered to the theories of the Arab Socialist Baath Party, which believed that socialism was the anathema of capitalism and that implementing on the ground it was the ultimate goal of the socialist society. Indeed, this was incorporated into the new constitution, which stipulated that Syria’s economic system was a socialist one. [3]

The late 1980s and early 1990s were one of the worst periods in Syria’s contemporary economic history. Public debt soared and large amounts of capital left Syria, against the backdrop of civil strife and escalating state repression. [4] Concurrently, the salaries of state employees declined in real terms, due to rising inflation, and the Syrian pound plummeted in value, from four to the U.S. dollar in 1980 to 50 just six years later, a collapse that was starkly reflected in prices. [5]

The Regime’s Approach to Socialism

Socialism, in its purist form, has been defined as “the abolition of individual ownership, meaning that an individual may not own land, a factory, a mine, or a wealth that requires a worker or workers to exploit it.” [6] Ownership of the means of production is collective, so the socialist nature of the system can be inferred from the question of ownership.

When Hafez al-Assad came to power in 1973, Syria’s economic system was, at least in theory, based on socialist principles. The constitution stipulated that society was to be built on “national socialist culture” and that the economy would be planned and socialist, with the aim of eliminating all forms of exploitation. In Article 14, it divided ownership into three categories: ownership of wealth by the people through nationalized institutions managed by the state; collective ownership including that of property belonging to cooperative associations and popular organizations, and whose welfare was guaranteed by law; and individual ownership—private property belonging to individuals, whose social function is determined by law in the context of serving the national economy, and the use of which may not conflict with the interests of the people.

The constitution referred to property in the context of individual, rather than private, ownership. Although individual property was required to serve the national economy and could not come into conflict with the property of the people, the Syrian regime left a margin for the private sector to ensure that the latter did not ally itself with the regime’s opposition—especially the Muslim Brotherhood, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In his 1978 Baath Party message, Hafez al-Assad called for “the revitalization of the private sector and efforts to remove the obstacles that have until now prevented the private sector from playing the full role that was expected of it in various economic sectors, while finding various ways to ensure that this sector carries out the responsibilities assigned to it and guarantees the investment of private funds into building the national economy, protecting them from all risks and ensuring it an acceptable level of profitability.” [7] In other words, Hafez al-Assad sought to make an alliance with the private sector, leaving it room for maneuver rather than imposing socialist policies on it, thus positioning himself as the protector of private property rights.

In practice, under Al-Assad senior, property in Syria was distributed along the following lines:

· Public ownership: This covered all of the state’s productive institutions, including those producing sugar, textiles, food industries, fertilizers, cement, and so on. The management of these institutions was handed to state employees seen as highly loyal to the regime, which turned a blind eye to their exploitation to accumulate private wealth, provided they functioned and met their minimum desired targets. One example was the Military Housing Corporation, which built military housing and facilities for the state; it was managed by the Shalish family, maternal cousins of the president, who managed to accumulate a huge fortune in this way, while Dhu al-Himma Shalish protected the president in return.

· Property of the ruling family: Natural and semi-natural resources, such as oil, tobacco, and other sources of wealth, were completely funneled to the benefit of the Assads and their cronies. Mohammed Makhlouf, Hafez’s brother-in-law and Bashar al-Assad’s uncle, is believed to have been the de facto manager of much of this wealth.

· Ownership by the people: State-run institutions were owned by the Syrian people, and provided services at discounted prices for the benefit of all Syrians. This category included bakeries; consumer associations that providing sugar, rice, and oil, electricity, water; the telecommunications sector; and public hospitals, which at the time provided a decent service to the Syrian public. These provided their services as social subsidies, i.e. at reduced prices.

· Private ownership: This was the status of shops and institutions for small or medium-scale industrial activities operating under tight security surveillance. Their owners were exploited or pressured by the government through taxes, security agencies or censorship, and were expected to allocate money to pay off officials who would protect their activities, in amounts varying according to the size of the establishment.

The form of private property in Syria under Hafez al-Assad, and its evolution under his son, can be understood as follows:

· Ownership in the livestock sector: During the reign of Assad the father, this was limited to Bedouin tribes who owned most of Syria’s herds of sheep and calves, and farmers who owned the remainer, mainly cows and poultry. However, there were also government institutions that owned livestock, most of which belonged to the Ministry of Agriculture or the Ministry of Defense. There was little private ownership of fisheries; the government owned the majority, exploiting the fish of Syria’s rivers and lakes, without making significant use of maritime stocks. When Bashar al-Assad came to power, there were minor changes. Some enterprises began to acquire their own animals to serve meat and chicken factories. However, in general, the form of ownership of most livestock did not change significantly, as the regime saw the Bedouins as an important group to keep on side, and it tried to avoid competing with them economically, in order to ensure their loyalty. The Investment Commission and large investors refrained from proposing large livestock projects, in order avoid any form of change in the distribution of ownership.

· Ownership in the agricultural sector: From early on in his reign, Hafez al-Assad’s regime relied on smallholdings, which were fragmented in line with the Baath Party’s socialist slogan of “land for those who work it.” An Agrarian Reform Law was passed to implement this notion, and much land was distributed to people from the coast and rural areas, which were particularly important to the regime. In contrast, the farmers of northern and eastern Syria continued to dominate the agricultural sector, with little competition, except from state bodies, which was the monopoly buyer of major agricultural commodities including cotton, wheat, and beet. As no other buyer was allowed to purchase these goods, farmers became indirect employees of the state. Under Bashar al-Assad, there were few significant changes in the nature of ownership in this sector.

· Commercial ownership: Under Hafez al-Assad, commerce was largely conducted by small and medium-sized traders. Larger operations were directly or indirectly linked to the regime, such as those run by Mehran Khonda, who supplied products for the army, and Saeb Nahhas, who had close links to Iran. A number of other smaller and medium-scale traders operated without privileges or support from the government, which did not try to boost the country’s international trade, for example.

With Bashar al-Assad’s arrival in power, a new class of merchants emerged, mainly from within the regime; the children and relatives of officials formed a new economic elite, dominating the commercial and service industries with the support of legislation, the security agencies and other institutions of the state.

The status of property within the commercial sector did not significantly change as a result, except in that officials who had managed public institutions under Hafez al-Assad were replaced with their children, relatives, or others in their stead, who continued operating under the new private sector. However, the regime retained the system of ownership within the president’s extended family. It is believed that instead of going abroad or remaining in banks, part of the family’s money was now invested in the Syrian market, through figures such as Rami Makhlouf, a maternal cousin of Bashar al-Assad. Private ownership also remained in place, but faced greater extortion by new economic actors in the private sector, and by state security officials.

Meanwhile, public ownership did not undergo any noteworthy change or modification, in contrast with other economic policies such as subsidies—for example, the disappearance of sugar ration coupons and their reappearance as diesel coupons, the introduction of electronic subsidies cards, and so on.

· Industrial ownership: The industrial sector in Syria barely grew during the Assad era. Most large factories were dedicated to assembly operations, while manufacturing was limited to small and medium-sized factories, due to the need for extensive financing, which was limited by international sanctions. Under Bashar al-Assad, a shift did take place in this sector, with the establishment of “industrial cities” and industrial investment, mainly by merchants from Aleppo, who invested billions in textile and clothing factories, and were able to export to the world. This class of young businesspeople appears to have wanted primarily to launder money and stay in fast-moving, light commercial operations, to ensure that they could make money quickly, rather than building a future for themselves and their children.

The Regime’s Approach to Capitalism

As far as ownership is concerned, capitalism generally takes a diametrically opposed view to socialism—but not necessarily in all cases. Capitalism relies on private ownership of the means of production in order to generate a profit. It also enjoys the use of a much broader range of tools than socialism. While the latter relies on central planning and executive oversight, its ideological rival leans heavily on private ownership in various areas, including monetary, financial, investment and other policy tools.

The Syrian regime, under both Assads, has implemented elements of capitalism in which regime loyalists own vast assets. Rami Makhlouf, for example, was authorized to invest in the telecommunications sector, as well as obtaining extensive rights in real estate and banking. State-related ownership was restricted to around five or six key figures in Syria, in the context of a shift to what it labeled a social market system, a subtle move closer to the capitalist approach.

The regime’s approach to capitalism and the market has been based on changing the form of ownership by transferring state funds from management to ownership. In the socialist approach followed by Assad Sr., the regime’s policy was based on public ownership and state management of assets. His son then began to move towards a policy of management and ownership, more in line with a capitalist approach. Accordingly, a portion of the ruling family’s wealth was invested in the Syrian economy.

The regime’s approach to ownership by the people did not significantly change until 2011. The state continued to provide subsidies and provide basic services, government institutions continued to employ large numbers of people, and certain social institutions were introduced that formed a kind of civil society—albeit one managed by the president’s wife Asmaa al-Assad—in the form of social support for the poorer classes. This especially benefited rural Alawites affected by the transition to the new regime, which saw the demobilization or retirement of many ageing Hafez-era officers who consequently unable to obtain additional income beyond their pensions. The private sector was exposed to state-protected competition, and assets remained under the ownership of the children of senior officials.

When Bashar al-Assad came to power, many expected that he would open up the economy by liberalizing the market, at least to a greater degree than he would liberalize politics. However, he instead began promoting the notion of the “social market,” which was interpreted as a kind of socialism-infused capitalism: capitalist in terms of the regime’s desire to scrap government and public sector institutions and entrust them to the new business class, and socialist in terms of maintaining the Baath Party’s values and its presence through the distribution of aid and subsidies, in which it had played a prominent role.

The Regime’s Approach to the Social Market Economy

The social market economy has been defined [8] as an economic system that balances social justice with the free market economy. The social market economy combines the free-market principles of capitalism with the social aspects of socialism.

Hafez al-Assad made no attempt whatsoever to apply the principles of the social market economy. When his son came to power, it became clear that there was a need to transform the way in which property and ownership were organized. Bashar al-Assad kept in place the slogan of “social justice,” as a synonym for socialism. [9] He worked to develop the notion of ownership and maintain the existence of the Baath Party as an ideological organ and one of the main tools of governance, given its irreplaceable capacity for social and political organization. The dissolution or complete marginalization of the party would have created a vacuum that could have been filled by other, less disciplined parties and institutions, which the regime feared could subsequently obtain what it saw as an unacceptable margin of freedom.

The regime’s economic goals were now focused on keeping the Baath Party strong and able to influence the public over the long term, and encouraging officers and officials to pumping their money into the Syrian economy through private investments. This approach had several aims, most notably:

· Attracting foreign investment: The regime’s shift towards a social market economy sought to attract foreign investment, specifically Western ones, in line with the new regime’s slogans of development and modernization. The regime needed to harmonize the socialist and capitalist approaches, albeit theoretically, so it retained the socialist principles of the Baath Party and involved them in this shift, through the party’s Economic Committee, whose head, Mohammad al-Hussein, [10] played a key role in designing the new economic approach. He was joined in this by Abdullah al-Dardari, who was head of the Planning and International Cooperation Commission until 2005, when he became Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs, [11] and Adib Mayaleh, governor of the Central Bank of Syria (CBS).[12] The resulting approach was a combination of Mayaleh’s liberalism, al-Hussein’s conservatism, and al-Dardari’s ability to adapt decisions and formulate compromises. [13]

· Incentivizing local investment: The regime encouraged the children of officials who had accumulated wealth under Assad Snr. to play a prominent role in the economy, investing their money in local enterprises. This was a prelude to steps it began to take as it sought a transition to a social market economy. The sons of officers and officials now invested their fathers’ money in many sectors. Notable among them were Rami Makhlouf, who invested heavily in the telecommunications sector, Bahjat Sulayman’s sons, who began to emerge as prominent businessmen, and dozens of other young, well-connected men who suddenly appeared at the forefront of the Syrian economy. The regime also worked to revitalize the private sector during this period, to incentivize people to invest their money domestically. “Industrial Cities” were established in Hassia, Adra, and Sheikh Najjar, for example, and private companies began to emerge and expand.

At that stage, there were virtually no major changes to the main service institutions such as bakeries, electricity, water, and so on. The regime developed a long-term plan to reduce spending on them and to remove subsidies, but this was done in a gradual manner so as not to provoke a violent reaction from society. For example, graduate engineers no longer had a statutory right to positions at a state institution, and the price of a liter of diesel or gasoline was raised. Thus began the gradual process of the government abandoning public institutions, allowing them to decline while maintaining their overall form and some of their services intact.

2. The Regime’s Economic Policies After 2011

After 2011, the Syrian regime shifted to the financial and monetary policies of a war economy, in response to the deterioration of the economy and its own financial capacities, which it worked to bolster in order to support its military operations and remain in power.

Fiscal Policies: Subsidies and Taxes

In early 2011, the regime was able to exploit state institutions and public property to confront mass protests against its rule. It threw public sector employees into the street, deployed snipers on the roofs of public buildings, and put hospitals in the service of the army and security forces, while killing and humiliating protestors and flatly refusing to address their demands. It also began giving open vacations to employees who represented a threat, while recalling others. Its first move to mobilize resources was to ensure its total control over those of the state, then using what was held by the banks—particularly the Central Bank of Syria—to arm its forces and pay their dues.

The regime also tapped into the fortunes of loyalist businessmen, such as Rami Makhlouf and others, to create armed militias. It allowed contractors to exploit money from villages it still controlled to finance its military operations, and started calling on every possible institution, business figure, governmental and semi-governmental body to raise funds, particularly to access spare parts from overseas. It also passed laws such as a new military service law and new passport regulations. Its policies came to focus on primarily on raising money and secure what it needed for the war effort.

In 2019, the regime began introduced the “Takamol” smart card, through which the public could obtain fuels such as mazut, gasoline, and domestic gas. [14] About two years later, vital foodstuffs such as rice, sugar, tea, and others were sold at a reduced price to specific segments of the population, according to certain controls.

In light of its declining financial capabilities, the regime now set about scrapping its decades-old subsidies policy, through an undeclared shift from general to more targeted subsidies. To achieve this, it gradually excluded certain categories from being eligible for subsidized consumer items, part of a move to redistribute government subsidies and reduce the numbers of beneficiaries. For example, owners of cars with a engines above a certain size were now no longer eligible for subsidies, as they were seen as not needing them.

The regime has continued to try to move away from subsidized commodities to a system of cash handouts. On June 25, 2024, the Council of Ministers issued a decision requiring electronic subsidy card-holders to open bank accounts within three months. This was followed by a notification issued by the Ministry of Finance on June 30, 2024 ordering public banks to increase their branches’ opening hours and to open on Saturdays, to enable subsidy card holders to open bank accounts.

Tax policies have also changed in several ways. The Ministry of Finance has made radical amendments to introduce a Value-Added Tax (VAT) and a unified income tax—as applied the capitalist systems. To this end a specialized technical committee has completed the first draft of a VAT law, which is expected to be in effect by the beginning of 2025, a step that coincides with the tax administration’s receipt of software for electronic invoicing, [15] which will be the executive tool of the new tax policy.

The regime has also made efforts to reduce the public budget deficit, which declined from 30 percent in 2023 to 26 percent of the total state budget appropriations, a step towards its target deficit of 20 percent. To achieve this, the Ministry of Finance has borrowed from the Central Bank to secure the required funding, and relied on domestic borrowing from the Syrian financial sector by issuing treasury bonds. However, this has proved to be a futile measure: rather than providing financial instruments to generate funding, the move increases inflation and inflict losses on lenders.

In summary, the regime’s fiscal policies have historically followed a mixed approach, with elements of both socialism and capitalism, by controlling public spending and increasing government revenues, which have also been hit by declining oil production and the absence of revenues from that sector. Its policies in this regard have fallen into three categories: Improving revenues from taxes and fees, enhancing income from public sector economic bodies, and increasing revenues from the investment of state property by managing these assets to generate a profit for the public treasury.

Monetary Policies: The Central Bank as a Model

The publicly stated goal of the Central Bank of Syria [16] is to maintain monetary and financial stability in order to support macroeconomic policy objectives, by building an effective and efficient monetary policy able to maintain a stable exchange rate for the Syrian pound and a low, stable inflation rate. This is intended to help provide a favorable environment for investment and to support economic growth. The regime has also adopted electronic payment tools in order to achieve short-term and long-term goals.

However, in practice, the bank no longer has effective policies. For example, it uses a fixed exchange rate for the Syrian pound against foreign currencies, rather than a flexible rate that would adapt to supply and demand in the market. It has also adopted an interest rate policy like those used in capitalist economies to curb inflation, but this has proven ineffective in reining in the lira’s precipitous decline. The central bank also helps manage bond sales carried out by the Ministry of Finance, another ineffective policy that causes losses to the holders of these bonds and plays no effective role in financing the budget deficit or reducing inflation. The Central Bank also stopped issuing the certificates of deposit it had issued between 2019 and 2020, [17] through which it took receipt of funds for a fixed period and at a specific interest rate. It dropped this policy due to lack of demand. The move to electronic payments, meanwhile, is still facing many obstacles related to the general financial and technical system at the Ministry of Finance.

It is clear that the regime’s monetary policies do not amount to the application of a social market economy. Nor do they mark a return to socialist policies. Rather, they are used as a sticking plaster to keep the economic situation under control, rather than serving a transition towards a more systematic or defined economic model.

Public Sector Management Policy: Company Mergers as a Model

In 2011, the regime issued Legislative Decree 29, [18] enabling it to sell any state-owned institution or facility, in whole or in part. The law created a new type of company, “wholly state-owned joint stock companies,” which allowed the state to sell public property by first transforming it into a joint stock company, subject to the approval of the Council of Ministers.

In late 2023, the regime issued a further series of laws that merged various companies and changed their legal status, as follows:

· Law No. 22 of 2024. [19] This established the “Public Company for Food Industries,” replacing the state-owned food industries and sugar firms and all their subsidiaries. The new law merged the two bodies and 25 production companies into one new company, with headquarters in Hama.

· Legislative Decree No. 98 of 2024. [20] This law established the General Company for Roads and Water Projects, replacing the General Company for Roads and Bridges and the General Company for Water Projects in all their rights and obligations, also with its headquarters in Hama. The General Company for Water Projects had been formed in 2003 by a decree merging what was then known as the Syrian Land Reclamation Company with the Syrian Irrigation and Drinking Water Company (Rima).

· Law No. 3 of 2024 [21] on the establishment, governance, and management of public joint stock companies, public joint stock holding companies, and standard joint stock companies. This new cluster of economic actors became the beating heart of the regime’s economy—but without incurring any obligation to publish accounts, feasibility studies, or analysis of market mechanisms and their repercussions.

· Law No. 11 of 2024, [22] which merged the General Organization for Cotton Ginning and Marketing group with the General Organization for Textile Industries—and all 40 of its subsidiaries—to create the General Company for Textile Industries.

· Law No. 26 of 2024, to invest, manage, and sell movable and immovable assets confiscated from citizens by court ruling, handing the investment process to the Ministry of Finance and the unregulated management of real estate to the Ministry of Agriculture.

· Law No. 43 of 2023, [23] establishing the General Authority for the Management, Protection, and Investment of State Property, which represents all state-owned real estate, whether built upon or not, and the state’s rights in kind, in its capacity as a public legal entity.

In general, the regime has adopted a strategy of categorizing and merging companies according to sector. That is to say, it takes all the companies related to a specific sector such as the food industry, and merges them. By doing so, it restructures companies affiliated with ministries such as the Ministry of Industry in order to create an organizational and legal environment that then enables it to transform these companies into joint stock, holding, or joint stock companies. It is then able to place a portion of their shares on sale or place it directly on sale through privatization. Thanks to the merger policy, one large company is offered instead of a group of companies. Moreover, these companies’ productive assets are gathered in one place geographically, consolidating their operations to prepare them to receive contracts from international donors in the event that of Syria receiving funding for early recovery and reconstruction projects, in order to meet donors’ conditions.

In other words, in its approach to managing the public sector, the regime is applying economic policies that reflect a general shift toward unplanned capitalism, in contrast to its previous use of socialist and social market policies.

Managing the Private Sector and the Shadow Economy

The regime’s Investment Law No. 18 of 2021 was issued on the pretext of “creating a competitive investment environment to attract capital, benefit from a range of expertise and specializations, expand the base of production, increase job opportunities and accelerate economic growth,” ostensibly to promote comprehensive and sustainable development. However, the number of projects granted under this law has not exceeded 89, in various sectors, at a total cost of 4.32 trillion Syrian liras, and created just 8,133 jobs since it passed into law. [24]

Thus, the regime’s drive to attract new capital to the private sector has not been effective. Such investment has remained depressed, and the private sector’s contribution to gross national income has declined. Despite the regime’s efforts to increase the private sector’s contribution to the economy, its contradictory policies, the absence of a clear economic model, and ongoing political instability have continued to prevent the emergence of a competitive and suitable investment environment. This has meant that its policies have been ineffective in paving the way for the implementation of the social market model, which requires a clear strategy to achieve stability and support investment opportunities.

On the other hand, the shadow economy has burgeoned, [25] contributing to widespread corruption in the formal economy, which, for its part, has weakened due to international sanctions and the emigration of labor and capital. This has pushed the regime to refraining from taking serious measures to control the shadow economy, despite repeatedly announcing its intention to review the legislative framework for conducting business in areas it controls, particularly with regard to taxes and legal procedures related to granting the necessary licenses and approvals. For example, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection has carried out several waves of campaigns on shops and factories with the aim of controlling the cost of goods and services, but due to bribery of its inspectors, it has largely turned a blind eye to violations.

Since early 2024, the regime has tried to demonstrate its determination to tackle the shadow economy through certain structural policies. The Tax Administration has announced the imminent launch of a billing system and a commodity coding system, [26] part of efforts to rein in tax evasion arising from the shadow economy, specifically targeting small and medium-sized business owners. However, these efforts have fallen short, as the drive to revitalize the formal economy is struggling in light of political and economic conditions that have led to an unprecedented decline. These efforts also appear futile, as the regime is unable to curb the shadow economy, which continues to expand, with both large and small business owners smuggling commercial goods and raw materials, as well as engaging in money laundering. The war has made the shadow economy has a force to be reckoned with—as well as a more attractive option than the real economy, from the regime’s own perspective.

3. The Business Elite in the Syrian Regime’s Economy

Throughout the various stages of its rule, the Syrian regime has relied on a clique of businessmen and economic figures. However, the composition of this group evolved between the eras of Hafez al-Assad and the first decade of his son Bashar’s rule, then again with the outbreak of civil conflict since 2011. Together, these figures have played a major role in perpetuating and preserving Syria’s financial resources, and thus the continued existence of the regime in power, alongside its deployment of different economic models and policies. The regime has worked hard to bring key business figures into its fold, ensuring their loyalty by dividing up and distributing key economic resources among them.

The Business Class Under Hafez al-Assad

Syria’s traditional economic elite saw its influence and wealth decline during the rule of Hafez al-Assad, but it continue to own substantial assets, enjoyed a prestigious social status, and stayed in legitimate businesses which generated huge profits—in exchange for their proprietors refraining from any kind of political activity. In many cases, a kind of rapprochement emerged between regime loyalists and the traditional wealthy class. Their lifestyles and behaviors became similar, and in some cases, their children married. [27] Hafez al-Assad relied on many figures to consolidate his rule, some of whom had security and military roles. They included Mohammad Dib Daaboul, [28] Mustafa Tlass, [29] Ali Haidar, [30] Asef Shawkat, [31] Ghazi Kanaan, [32] Bahjat Sulayman, [33] and Fawaz al-Assad. Some of these men also played administrative or economic roles.

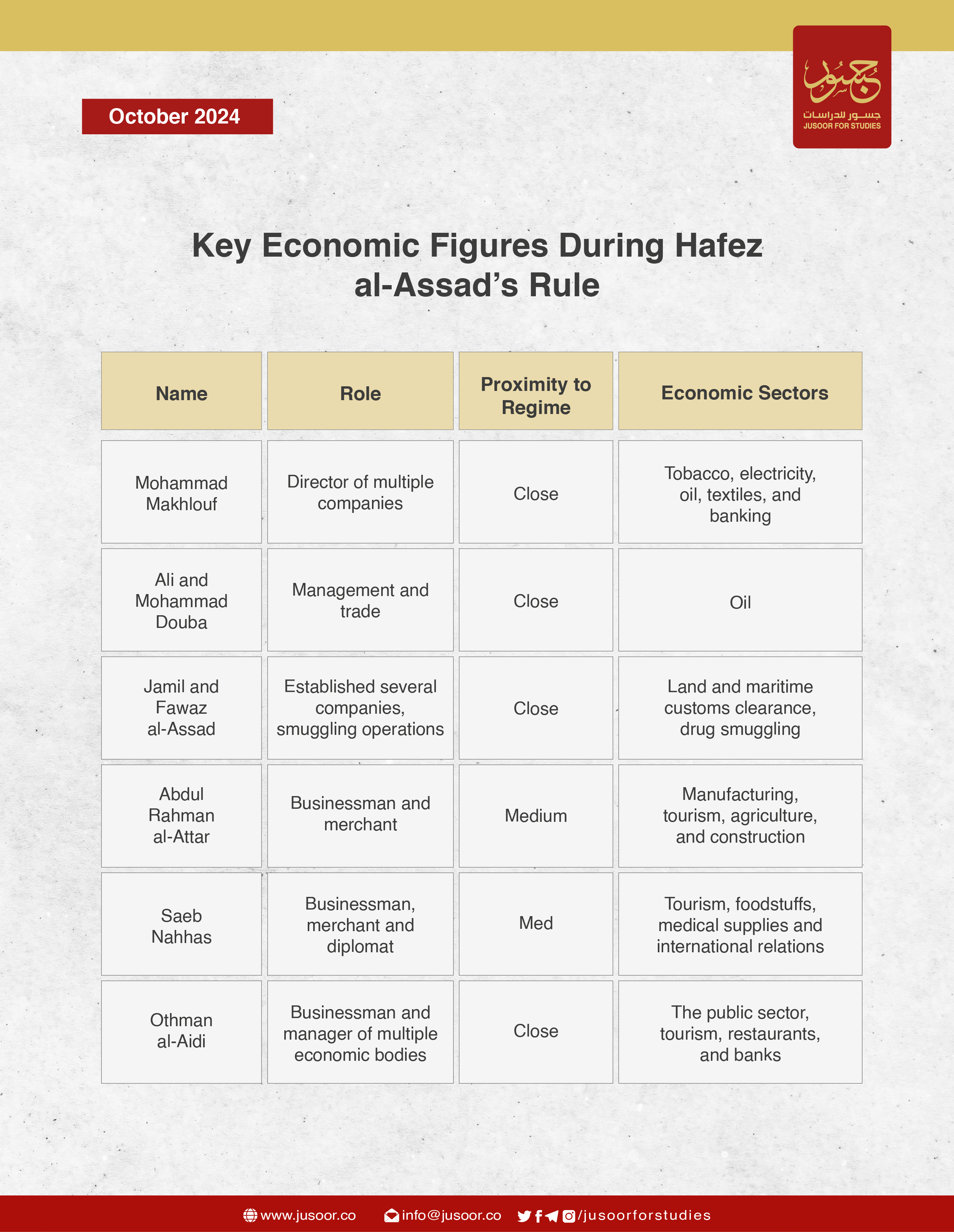

The following played particularly prominent roles in the Syrian economy during Hafez al-Assad’s rule:

· Mohammad Makhlouf: The brother of Assad’s wife, Anisa Makhlouf, he became the director of Syria’s General Tobacco Corporation in 1972, two years after Assad came to power. He then proceeded to build an economic empire, which came to include the oil sector, through the Euphrates Oil Company and the Lead Contracting & Trading Company, and projects in the fields of electricity, textiles, and banking. In 1985, he became the director of the Real Estate Bank of Syria (REB). He was the father of Rami Makhlouf, who inherited his father’s economic empire.

· Ali and Mohammad Douba: Key figures in Syria’s oil industry. Mohammad managed the Syrian Oil Company until 1990, and the two passed on their business to their sons Samer, Aktham, and Amjad.

· Jamil al-Assad: Hafez al-Assad’s brother, Jamil began building an economic empire by establishing the Al-Sahel Customs Clearance Company, which operated branches at land and sea border crossings, and came to dominate the customs clearance process. Jamil was the father of Fawaz al-Assad, a notorious smuggler of cigarettes and narcotics during the first Assad presidency.

· Abdul Rahman al-Attar: A businessman and head of the Syrian Red Crescent under both Hafez and Bashar al-Assad, until 2016. His father, Mustafa al-Attar, was a food merchant and the Secretary of the Syrian Association of Islamic Scholars ( ulema ). Abdul Rahman founded the Attar Commercial Group, which is active in many fields such as the pharmaceutical industries, agricultural and tourism projects, cardboard manufacturing, and civil contracting. The group also held the franchises for several branches of Sony, Ericsson and IBM, and many hotels such as the Carlton Hotel, Al-Firdaws Tower in Damascus, and Zenobia Cham Palace Hotel in Palmyra.

· Saeb Nahhas: A prominent entrepreneur who started his business career in 1953, and came to own a large group of companies operating in various economic sectors, such as tourism, food, medical supplies, and others. He also held the position of Honorary Consul in Syria for both Mexico and Kazakhstan, and acquired many international outlets. The regime tasked him with strengthening trade relations with Iran and Hezbollah. During the era of Bashar al-Assad, he expanded the scope of his business in a number of Arab countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Jordan and Sudan, in addition to other countries such as Mexico and Kazakhstan.

· Othman al-Aidi: Al-Aidi served as Chair of the Board of Directors of the Syrian Company for Tourist Facilities, which was established in 1977, and Chairman of the French Hotel Group Le Royal Monceau. He was also head of the International Hotel & Restaurant Association between 1993 and 2021, and led the Euro-Mediterranean Tourism Organization (EMTO). He was a co-founder and board member of the bank Bankmed SAL in France and Lebanon, and contributed to many development projects such as auditing engineering studies for the construction of the Rastan and Muhradah Dams, and implementing irrigation networks in the Sahl al-Ghab Plain. Hafez al-Assad awarded him the Syrian Order of Merit.

Finally however, a dispute between Hafez and Rifaat al-Assad resulted in millions of dollars-worth of foreign currency reserves being taken out of Syria, to acquire luxury real estate in London, France, Spain and other European countries. This led to the formation of a new class of former officials who took part of their wealth outside the country, to start new lives in the financial and business sector. [34] The remaining elite was unable to keep its private property separate from public property or bring it into the open, for various reasons. [35]

Syria’s Business Elite in the Early Bashar al-Assad Era

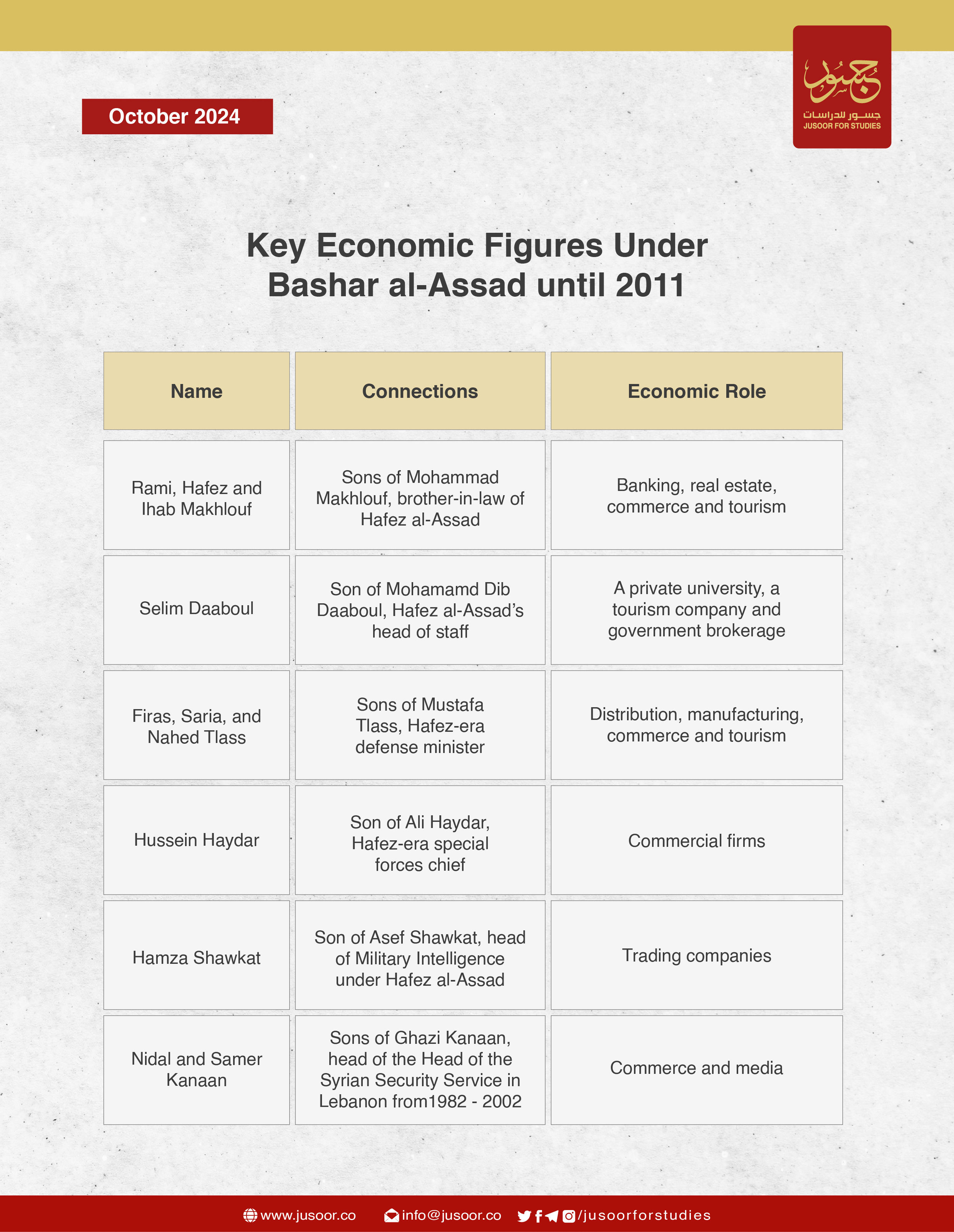

After Bashar al-Assad came to power in 2000, a new class of economic figures began to emerge, namely the children of security, economic and military officials from his father’s era who had benefited from the their own fathers’ influence and connections. The young president put this class and his mixed policies to the task of restructuring and developing the economy, managing domestic funds and forming partnerships with foreign countries in order to attract investment. The most prominent figures in the new class were the following: [36]

· Rami Makhlouf: The son of Mohammad Makhlouf and maternal cousin of Bashar al-Assad, Rami Makhlouf is a prominent businessman who has been one of the most important economic figures in Syria under his cousin’s rule. Makhlouf benefited from his father’s influence and invested in many sectors, including Syria’s mobile network provider Syriatel and in the telecommunications sector in Yemen. He owned shares in the Al-Mashreq Investment Fund and Corniche Tourism, and was active in the cement, gas and oil sectors. He held the BMW franchise in Syria and established a car testing company in cooperation with the son of a former Lebanese president. He was a key financier of the regime from 2011 onwards, through his Al-Bustan Association. However, this was forced to close down in 2019 and Makhlouf was completely shut out of the country’s economy from early 2020, following a dispute with the president.

· Ihab Makhlouf: Another son of Mohammad Makhlouf and cousin of Bashar al-Assad, Ihab has acted as a director and partner in a variety of companies, including the Islamic Company for Brokerage and Financial Services, Peshawar Investment, Syriatel, and others. He is seen as the right hand of his brother.

· Selim Daaboul: Son of Mohammad Dib Daaboul, Selim owns more than 25 companies in various economic sectors, such as Al-Nibras Company and the private University of Kalamoon. He was a founding partner in several other companies, and enjoyed a close relationship with Bashar al-Assad.

· Firas, Saria, and Nahed Tlass, sons of Mustafa Tlass. Firas founded a group of commercial and investment companies including the Palmyra real estate development company and the MAS group, active in the coffee trade, metal production, and canned foods. Tlass also owns multiple companies in the food and real estate sectors, in addition to having strategic partnerships with international companies, such as France’s Lafarge, which specializes in cement production. Firas, was known as the king of the sugar trade in Syria until 2011, while Nahed and Saria are partners and founders in many companies including MAS, the MAS Metal Coverings Company, and the Syrian Meat Manufacturing Company.

· Hamza Shawkat: Son of Asef Shawkat, active in many economic sectors such as aviation, trade, and others. A partner and founder of many companies such as the Shawkat and Al-Husseini Company and Vision Plus.

· Nidal and Samer Kanaan: Sons of Ghazi Kanaan, active in many economic sectors and partners and founders in multiple companies, including the Middle East Company for Modern Technologies and the Middle East Company for Quality Products.

· Aktham and Samer Douba: Sons of Ali and Mohammed Douba, worked in many economic sectors such as sports and media, among others. They were founding partners in several companies, including the Syria Trust for Development, Kawalis, and the Zuhal publicity agency. Samer was an oil smuggler, and took over the management of the family’s funds after Mohammed Douba disappeared in May 2012.

· Mohammed Hamsho: A friend of Maher al-Assad, Hamsho is a prominent businessman in the areas of communications, advertising, marketing, and artistic production. He founded Syria International for Artistic Production and the Sham Press news website. He was also a partner in Al-Dunya TV, and founded the Hamsho International Group, a contractor for residential and government facilities, which has several affiliated companies.

· Majd Sulayman: Son of Bahjat Sulayman, Majd has worked in many sectors including media, communications, banking, tourism and real estate. He is the founder of the advertising and publishing firm United Group, which specializes in publishing newspapers and artistic and advertising magazines in Syria and in Arab countries such as Al-Wasit, Layalina and Baladna. He is also the executive director of the International Al-Wasit Group.

· Sulaiman Mahmoud Maarouf: A son of Mahmoud Maarouf and friend of Bashar Al-Assad, Sulaiman founded a number of companies and managed some, in various sectors such as banking, tourism, media, cars and others. He was also an agent for Honda in Syria and a founding shareholder in the Sham Holding Company as well as General Manager of Al-Shahba Media Company, and a founding partner in the International Islamic Bank of Syria, among other companies.

· Ayman Jaber: A friend of Fawaz al-Assad, Hafez’s brother, Ayman Jaber is a prominent businessman who founded the Iron and Steel Council in Syria and entered into investments and contracting. He helped establish the Sham Holding Company and the Al-Dunya satellite channel, and owns the Arab Iron Rolling Company. He owned several companies in Lebanon such as the United Jazeera Company for public transport, as well as in other areas such as oil derivatives trading and services, and other companies. He is also known for having an active smuggling business.

In general, after Bashar al-Assad took power, he turned his back on socialism, enabling hundreds of businessmen who had been extremely loyal to his father to preserve their gains by managing factories and institutions owned by the state. He worked to introduce the social market system, to remove the exclusive monopoly over resources from the hands of government factory managers and senior officials.

However, on the other hand, he gave their sons the opportunity to obtain investments in various sectors, as provided for by new laws. Thus, Syria became a playground for a new economic elite with extensive wealth and influence, but without the regime doing away with the traditional bourgeois class allied with Assad the elder, which indeed began to expand during Bashar al-Assad’s reign.

Syria’s Business Elite since 2011

As Syria descended into civil war in 2011, a new economic elite emerged. Some exploited and profited from the vacuum created by the exodus of more established traders from the market, while some exploited the remains of looted homes whose owners had been forced to flee. Some of the new business class also amassed vast fortunes by facilitating trade between various enclaves of the war-torn country. Rivalries also emerged between certain figures who had emerged after Bashar al-Assad came to power and made huge gains. These new actors did not belong to the traditional business class, nor were they the sons of officials who had used the connections of their fathers to build their own fortunes.

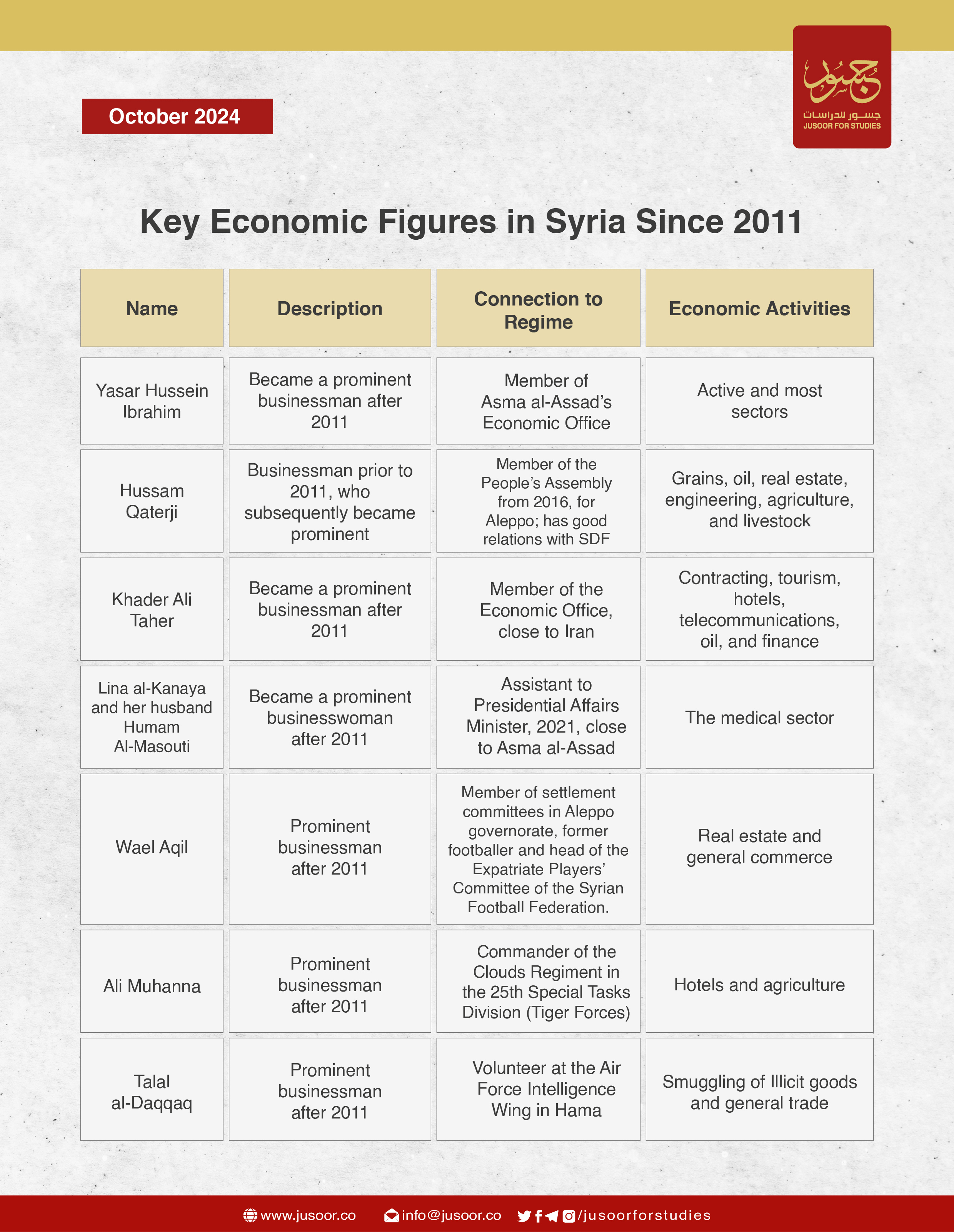

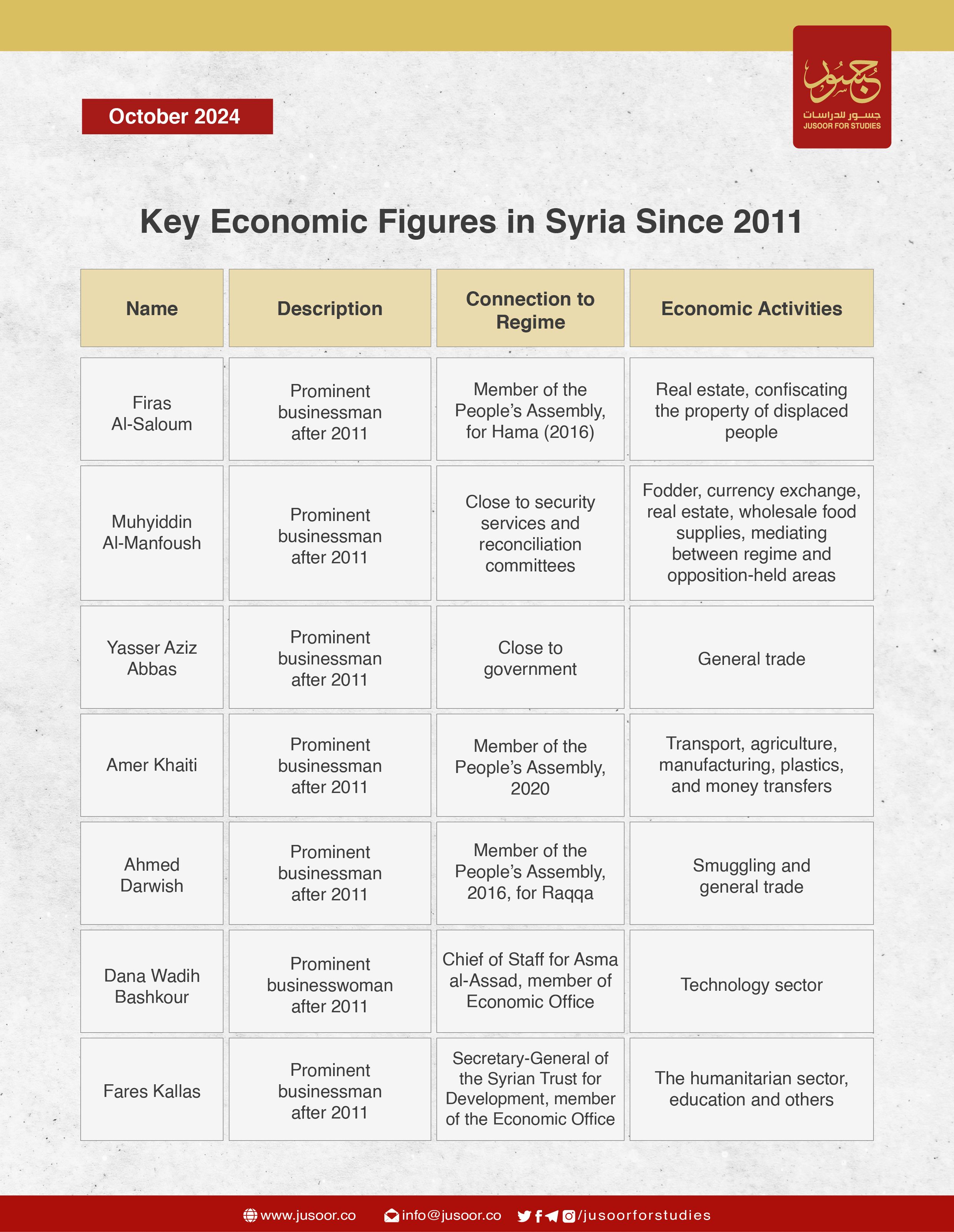

The dynamics of the war contributed to the rapid rise of new economic figures, who exploited the situation to make huge fortunes. Many of them carried out risky work and built their own networks of relationships from scratch. Some benefited from the their cities or villages being located on the front lines, or from their clan or family connections. Some examples include: [37]

· Yasar Hussein Ibrahim: Ibrahim was an unknown quantity before 2011, but thanks to his father, who was the head of the Remote Sensing Authority, he had ties with the presidency. He worked as an official in the “Office of Martyrs’ Affairs” linked to Asma al-Assad, and in 2018 he took on an executive position in the Economic Office, a secretive operation run by the first lady, where he was tasked with collecting royalties from traders and industrialists under threat of having their property seized or facing arrest. Among the figures he pressured in this way were Rami Makhlouf. Ibrahim seized shares in the country’s third-largest mobile phone operator, Wafa, and worked in the secret office with his older sister Nisreen Ibrahim, who has closer ties to the presidential palace than her brother, and held the position of Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors of MTN between 2020 and 2021. He also worked with his younger sister Rana. Their close ties to the president gave them opportunities to manage companies in most economic sectors, including the Al-Burj Investment Company, tourism firm Ziyara, the Central Cement Manufacturing Company, the Castle Investment holding company, the Bazaar Foundation, the Wafa telecommunications company and Al-Ahd for Trade and Investment. In early 2024, he exited the business world, saying he had been poisoned.

· Hussam Qaterji: Qaterji was a minor real estate actor before 2011, but following the revolution, he founded or co-founded multiple companies, including Qaterji Mechanical Engineering Industries, Arfada Petroleum, the Qaterji Trading Company, Qaterji Holding Group, Ara for Studies and Consulting, and the Juzur Group for Agriculture and Animal Husbandry. He made a fortune from trading oil and grains with both the Islamic State group and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and became better known that than his relatives and brothers, who include Mohammad Bara Qaterji, Mohammad Agha Qaterji, Ahmad Bashir Qaterji, Mohammad Fadi Qaterji, and Mohammad Bashir Qaterji. In 2016 he was elected to the People’s Assembly, representing Aleppo Governorate.

· Khader Ali Taher: Prior to the 2011, Taher was a little-known figure in the poultry industry, but during the revolution he became a member of the Economic Office and one of the regime’s key businessmen. He benefited in this from his close ties to Brigadier General Ghassan Bilal, head of staff for the president’s younger brother and head of the 4 th Armored Division, Maher al-Assad’s, as well as his own close ties with Iran. He was involved in collecting taxes at checkpoints and internal crossings between regime and opposition-controlled areas, and external crossings, especially with Lebanon, in addition to trading in oil. He managed and owned companies in various sectors such as contracting, tourism, hotels, communications, and security, and amassed enormous wealth through companies he managed, which became active after 2017, and which served to launder money from crossings and illegal smuggling operations. On February 20, 2019, Interior Minister Mohammad Rahmoun issued a circular prohibiting the ministry and police units from dealing with him, but this circular was only in force for a few days, until another was issued on March 10, stipulating the cancellation of the first, due to an intervention by Maher al-Assad.

· Lina al-Kanaya: She had no known commercial activity before 2011, but since the start of the revolution she has owned multiple companies, benefitting from her position as Assistant to the Minister of Presidential Affairs in 2021, and her relationship with Asma al-Assad. She has built a fortune along with her husband Humam Al-Masouti, who after their marriage rose from being an employee at a public hospital to a businessman working in securing medical tenders for public entities. He also established relationships with prominent economic figures such as Mohammad Hamsho and Samer Al-Debs, and founded several companies including Roshana.

· Wael Aqil: A small-scale trader and real estate investor before 2011, Aqil is the son of a relatively wealthy family as well as being a former player in the Al-Ittihad Football Club (Al-Ahly Aleppo) and the former president of the Police Club. He mediated the release of many detainees as well negotiating local reconciliation agreements, which allowed him to establish businesses and buy real estate in besieged areas, where he had more information than his competitors. Obtaining a share of the ransoms for his mediation efforts provided him with additional income, enabling him to own commercial markets in the heart of the capital, and partnerships areas other than Aleppo.

· Ali Muhanna: Muhanna was a laborer with no known business activity before 2011. Following the revolution, he led a small group of his villagers in carrying out organized kidnappings and robberies. He soon entered the regime’s 25th Division for Special Tasks (the Tiger Forces) and assumed command of the “Clouds Regiment”. He took control of vast pistachio orchards and drew profits from harvesting them, as well as exploiting the presence of regime forces near crossings to smuggle fuel between opposition areas and regime areas. He became deeply involved in the shadow economy through restaurants, hotels, agricultural lands, and transportation companies, in addition to owning a fleet of luxury cars. Muhanna has relied on other figures to expand the scope of his business, including Talal Al-Daqqaq, who has helped him invest in the real estate sector in Hama city, and to buy several gas stations on major highways roads, along with restaurants and clothing stores.

· Firas Al-Saloum: a little known real estate contractor in Homs Governorate before 2011, he built his wealth by getting close to the regime’s military and security apparatus and by seizing money and property from the displaced. Since 2016 he has been a member of the People’s Assembly for Homs Governorate.

· Muhyiddin Al-Manfoush: A well-known businessman in the cheese and dairy industry sector before 2011, he is the owner of dairy firm Almarai Aldemshkieh. Since the start of the revolution, his wealth has grown through commercial operations between opposition and regime-held areas, and his work in various sectors such as fodder, currency exchange, real estate and food trade.

· Yasser Aziz Abbas: A little-known businessman prior to the revolution, he has since amassed a fortune by selling general supplies to the regime. He has founded and managed various companies, such as Al-Malik al-Shab, Tafawuq Tourism Projects, Qimmat Al-Aamal, Qudra Trading, Al-Bajaa Commercial Services, and Al-Khutawat Al-Saba’a Consulting.

· Amer Khaiti: Unknown prior to the revolution, since 2011 he has participated in the founding and management of several companies, including the Bidaya Group, Al-Amer Real Estate Development and Investment, Ard Al-Khairat, Al-Laith Al-Dhahabi for Transport and Shipping Services, the Al-Amer Company for the Manufacture of Cement, Blocks and Tiles, the Al-Amer Company for Plastic Manufacturing, and Al-Saqr for Money Transfers. He is a member of the People’s Assembly for the Rif Dimashq Governorate elected in 2020.

· Ahmed Darwish: Darwish is not known to have been involved in any business activity prior to 2011, but since this date he has been able to make millions of dollars through the trade of goods and transfer of people across front lines. He is a member of the People’s Assembly for Raqqa Governorate elected in 2020.

· Fares Kallas: A businessman with a relationship with the presidency prior to 2011, he later became the Secretary-General of the Syrian Trust for Development and a member of the Secret Economic Office. He is believed to have played a major role in bridging the humanitarian and for-profit sectors, founding and managing companies in various sectors, including the Ugarit Educational Company, the National Microfinance Foundation, and Al-Manara Private University.

· Dana Wadih Bashkour: Little is known about her activities before before 2011, but after this date she became the director of Asma al-Assad’s office, and a member of the Secret Economic Office. She owns a stake in software firm Alpha Incorporated.

These a few examples of members of the new economic elite who have built their fortunes since 2011. Using their close ties to the regime, each of them established a foothold in the business sector in Syria, and built their own networks of relationships, not in the same way as the sons of officials who had made their own fortunes since Bashar al-Assad took power by benefiting from the authority of their fathers, but rather by exploiting the circumstances created by the war. They have not neglected the importance of force in maintaining the economic gain they achieved; they have built close ties with military and security personnel such as officers from the Tiger Forces or the Fourth Division. Some of them, such as Rafed Jarous, also established relationships and partnerships with Hezbollah, or with Russian officers and officials, such as in the case of Wael Aqil. [38]

Although some of these figures owned well-known businesses prior to the revolution, after 2011 they were able to build far bigger fortunes based on their relationships with the regime and their ability to navigate the war economy. This also gave them a place in the political scene, in the cases of Amer Khaiti and Hossam Qaterji as members of the People’s Assembly, or Yasar Ibrahim and Lina al-Kanaya, who worked as members of the Secret Economic Office affiliated with the presidency. [39]

4. The Syrian Regime’s Economic Decision-Making Mechanism

The economic decision-making mechanism is an important factor in understanding the economy of the Syrian regime, which has followed various economic approaches throughout its rule, as explained in the following sections.

The Era of Hafez al-Assad (1973-2001):

Hafez al-Assad did not have a comprehensive vision for the Syrian economy, but his accession to power via the Baath Party meant he largely adopted the party’s vision, mechanisms and economic policies by default. These were approved at national and regional conferences, where the party’s central committee and the government adopted them and transformed them into concrete policies through five-year, ten-year and sometimes three-year plans. However, this process meant that any national vision for the economy was subordinated to party agendas. In other words, decision-making was in the hands of the Baath Party rather than the government, which became merely a tool for executing the party’s plans. Thus, they were subject not to the state’s supervision and control, but rather to that of Baath party committees. This was backed up by Article 8 of the 1973 Constitution, which enshrined the Baath Party as the leader of the state and society.

This mechanism concentrated the power to make economic decisions in the hands of Hafez al-Assad, in his capacity as Secretary-General of the party and President of the Republic. As all party and government leaders were subordinate to him, he was able to change economic policy on the recommendation of his Special Economic Office at the presidential palace, which consisted of a small number of highly loyal advisors.

Bashar al-Assad’s Early Years (2000-2011)

When Bashar al-Assad came to power, he needed to unveil new economic policies and better decision-making mechanisms and governance. In 2005, he convened the Baath Party’s 10 th national conference, where it was decided to transition from a socialist approach to a social market economy. One of the requirements of this was to create a new legal and administrative environment, as well as creating advisory or governmental bodies and new positions in the Council of Ministers. One such position was that of Economic Assistant to the President of the Council, which was assumed by Abdullah al-Dardari, to manage the economic transformation.

In the meantime, Bashar al-Assad beefed up the Economic Office, exploiting the legal and administrative environment to build an economic empire within the regime for the benefit of the his extended family, concentrating wealth in the hands of his clan in a way that his father had never done. Thus, the Economic Office transformed from a mere advisory office to a supervisory and executive body, binding all party and governmental bodies and economic actors to its decisions. Thus, decision-making became centralized in the presidential palace, at the expense of the declining role of the Baath Party, which in 2005 lost the authority it had enjoyed though its five-year and ten-year plans.

Economic Decision-Making Since 2011

The mechanisms for taking economic decisions remained concentrated at the presidential palace, but this approach shifted according to the needs of the moment. In 2016, Bashar al-Assad entrusted his wife with managing the Economic Office. She restructured it, excluding technical and advisory figures in exchange for employees loyal to the palace, most of whom belonged to the Syrian Trust for Development. They included Lina al-Kanaya, Khader Ali Taher, Yasar Hassan Ibrahim, Nisreen Hassan Ibrahim, Dana Wadih Bashkour, and Fares Kallas.

The office’s mission at that stage was to develop policies to gather money from warlords who had accumulated fortunes after 2011, as well as finding ways to evade Western sanctions by creating new shell companies. Since 2020, the office has focused on creating an environment for attracting money from international donors through humanitarian and early recovery aid.

The presidential palace kept a tight hold on the decision-making process until 2023. Under this system, the government and the Baath Party were merely tools for implementing economic decisions. However, since this date, the president has changed course in response to international and Arab pressures regarding the re-normalization of relations. Namely, the Economic Office and Asma al-Assad were sidelined, while the central leadership of the Baath Party and its Central Economic Office were activated, in an effort to restore the party to a primary role in economic planning and decision-making. This was despite the 2012 constitution’s abolition of the party’s role in “leading the state and society,” and had the aim of keeping powers concentrated in the presidential palace or the party, rather than the structural and organizational tools of the state, especially the government.

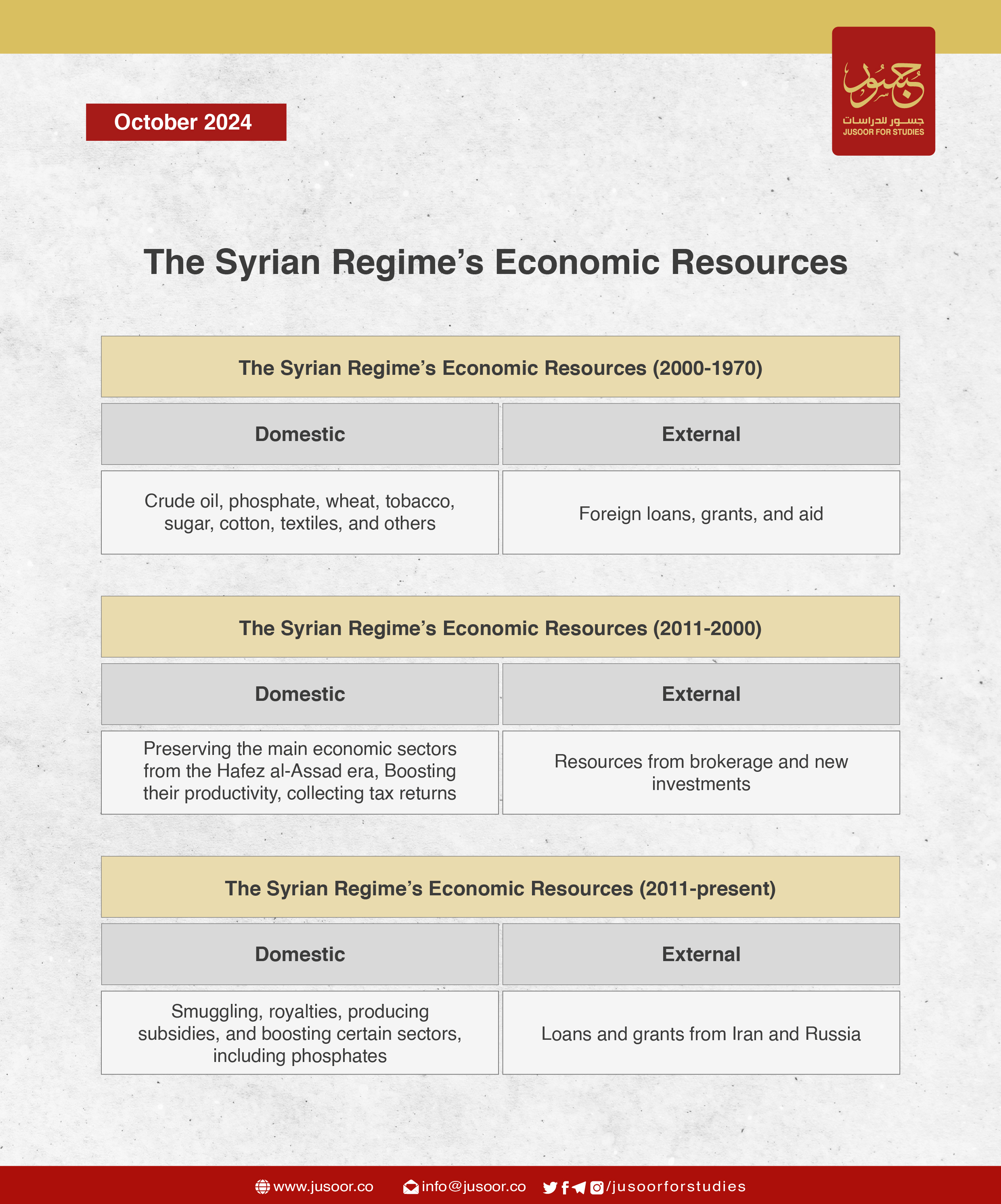

5. The Syrian Regime’s Economic Resources

Minerals and Oil

Hafez al-Assad made great efforts to exploit Syria’s natural resources, especially phosphate and crude oil, which were the country’s main resources from when he took power right up until 2011. Assad Snr. monopolized this sector to finance the presidential palace, benefiting from a policy whereby oil revenues did not appear in the state budget, while the accounts of the Ministry of Oil were submitted directly to the palace, on the pretext of needing these revenues to cover military expenditures.

Hafez al-Assad’s regime worked to increase production from these resources and to maximize its returns. For example, the annual production of phosphate increased from 857,000 tons in 1975 to 2.16 million in 2000, and the production of crude oil increased from 9.57 million cubic meters in 1975 to 31.68 million in 2000. After Bashar al-Assad took power, he continued with this approach, increasing phosphate production to 3.16 million tons in 2010, and maintaining good production of crude oil, which by 2010 had reached approximately 21.74 million cubic meters.

After 2011, most of Syria’s natural resources fell out of the regime’s control and into the hands of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). There was also significant damage to the sector, and production decreased to record lows. For example, phosphate production fell to 597,000 tons and crude oil to 1.56 million cubic meters in 2015. Later, the regime returned to focusing on increasing phosphate production, benefiting from investments by Russian and Iranian companies, pushing output back up to 2 million tons in 2022. However, the regime was unable to restore the level of crude oil production due to the fact that the main wells remained beyond its control, so it resorted to operating a few small wells that did not produce more than 4.71 million cubic meters in 2022.

This situation has obliged the regime since 2012 to rely on oil supplies from areas run by the Kurdish-dominated Autonomous Administration and Iran, as the regime itself produces just 20,000 barrels per day, or 10 percent of its daily needs, from the wells it controls. It secures a further 30,000-50,000 barrels per day, at best, from SDF-dominated areas—providing these supplies are not affected by military attacks or sabotage, logistical problems, or disputes over sales agreements. In summary, the regime secures at best some 70,000 barrels, or between 25 and 35 percent of its daily needs, domestically.

In order to cover the shortfall, it imports an estimated 3 million barrels per month, or 100,000 barrels per day, from Iran. However, these quantities change according to supply-side variables, obstacles to delivery, and contract disputes. At best, Iran supplies 50 percent of the regime’s daily oil needs. However, in reality this rarely happens: sometimes the Islamic Republic can barely provide more than 50,000 barrels per day, or 25 percent of the regime’s needs.

Therefore, since 2011, Syria’s natural resources have no longer constituted a major resource for the regime. Rather, the burden of securing oil needs has become a major concern as it seeks to cover its military and security needs and provide public services such as electricity, transportation, and communications.

The Agricultural Sector

Syria’s agricultural sector has traditionally been among the greatest contributors to the country’s GDP. Hafez al-Assad relied on it for Syria’s food security, and benefited from the fact that it does not require high operational costs or technology compared to the industrial sector, while delivering satisfactory returns. The regime has continued to support the sector, and increased the production of the most important crops, such as wheat (from 2.23 million tons in 1980 to 3.10 million in 2000), tobacco (from 14,000 tons in 1980 to 20,000 in 2000), and cotton (from 325,000 to 1.08 million in 2000).

Bashar al-Assad continued with the policy of supporting the agricultural sector out of the public budget, to meet Syria’s food security needs, as well as to empower the sector and enable it to deliver production inputs to the industrial sector—part of his plan to raise the latter’s productivity too. The agricultural sector represented more than 19 percent of Syria’s total output until 2011, and the production of major crops increased to reach 3.86 million tons of wheat, despite the country being forced to import the grain for the first time in 2008; cotton production increased to 671,000 tons, and tobacco production remained steady at 17,000 tons.

Between 2011 and 2013, the agricultural sector and its agricultural and industrial crops were greatly damaged by the escalating military conflict. After 2014, farmers began to flee the country, leading to a collapse in production. For example, by 2022, wheat production had fallen to approximately 1.55 million tons, cotton production reached 6,700 tons, and tobacco production had receded to 9,800 tons.

In summary, the agricultural sector ceased to be a key economic resource for the Syrian regime, covering the bulk of the needs of other sectors. It is acutely needs to be rehabilitated and restructured, which does not seem possible in light of the absence of a comprehensive strategy and the state budget’s inability to bear the associated costs.

The Industrial Sector

Industry is Syria’s second-biggest economic sector. However, under Hafez al-Assad, the regime did not provide a legal and economic environment to promote this sector, citing the pretext of high costs and the need for technology and technical expertise. Moreover, the regime was seeking to win over impoverished farmers, especially in coastal areas, to serve in the military and security establishment, and took little interest in promoting industrial development which would have restored the influence that the urban economic elite in Syria’s major cities had enjoyed before 1970.

Hafez al-Assad did however focus on developing the food industry to meet local needs. For example, sugar production increased from 117,000 tons in 1975 to 158,000 in 1995. The investment law he issued in 1991 was focused on the services sector, and had little impact on the industrial and agricultural sectors.

After the year 2000, the economic situation shifted in favor of groups that supported the regime through the army, security forces, and the presidential palace. These figures had amassed great wealth and influence, and when Bashar al-Assad took power, he was forced to respond to their demands for a regulatory and legal environment that would allow them to invest in the manufacturing sector. Partnerships began to emerge between officers and businessmen in major cities such as Damascus, Aleppo and Homs after the regime adopted the principle of the social market economy in 2005, providing facilities for manufacturers, establishing industrial cities and serving them with the necessary infrastructure. The sector now gradually began to grow, regime also attempted to cover the costs of the infrastructure it needed, by attracting foreign investment.

After 2011, the industrial sector was severely damaged by fighting, and came to the brink of collapse. Most industrial investors left the country due to the lack of security and other basic necessities for investment, and industrial production ground to an almost complete halt between 2014 and 2017. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, it declined from 355 billion to 61 billion compared to 2010 according to 2014 market prices, meaning the sector’s productivity was close to zero once inflation is taken into account. In terms of GDP, the industrial sector’s contribution declined from around a quarter to less than eight percent between 2010 and 2014—noting the fact that total GDP itself declined steeply. [40]

Overall, the benefits the regime had previously drawn from the industrial sector declined to nearly zero. It has not proposed any investment policies or plans for the sector since 2018; its industrial cities remain unsafe, and it has not sought to create suitable conditions for investment in them, on the pretext that it needs more financing in order to rehabilitate industrial infrastructure—something it is unlikely to achieve in the absence of the basic security that would enable or attracts investors.

The Commercial Sector

Syria’s geographical location has made trade a vital sectors for the regime, which has relied heavily on the sector’s financial returns since before 2000, especially by encouraging domestic trade at the expense of foreign trade and refraining from creating a legal and investment environment to develop the latter. Hafez al-Assad limited import and export activity to his key loyalists, ensuring that Syria remained isolated from its surroundings, in contrast with the needs of international trade for openness, stability and cooperation.

After 2000, Bashar al-Assad broke with his father’s policies and moved to greater openness towards the outside world, in response to the needs of the social market approach that he had adopted and to international pressure. He created a new legal framework to facilitate international trade and transport, and benefited from foreign investments to improve the road and transportation network, as well as rehabilitating border crossings. This, and an increase in the number of merchants, helped to increase the volume of exports and imports.

After 2011, with the imposition of economic sanctions on the Syrian regime and figures close to it, and as Lebanon tumbled into a financial crisis, exports and imports decreased significantly and remained limited to a few countries in the region. The resources of the commercial sector receded at a record rate, and the sector was mainly limited to domestic trade, with the bulk of revenues coming primarily from illegal activities such as smuggling across external and internal crossings, and through drug trafficking, the revenues of which grew and reached $5.7 billion in 2021 alone. [41]

The Financial Sector

The financial sector, which generates fees, taxes, and customs duties from various economic activities in addition to profits from government bonds, has constituted an important source of revenue for the Syrian regime since the era of Hafez al-Assad, as have domestic and foreign external loans and grants, especially those provided by the Gulf Arab states.

However, the financial sector remained within the public sector; the elder Assad did not allow for the creation of a suitable environment for private banking financing institutions to operate. When Bashar took power, he sought to expand revenues from the sector in order to meet the requirements of the social market approach that he had adopted, and in response to international pressures. The regime needed to find the necessary financial means to expand the industrial and commercial sectors, especially after Syrian forces withdrew from Lebanon in 2005, ending its influence over the Lebanese banking system which had hitherto enabled it to secure financing facilities. The regime now proceeded to create a legal and regulatory environment that would allow the establishment of a banking system affiliated with the private sector and private financing institutions.

Starting from 2005, the regime sought to develop the work of the Ministry of Finance to achieve greater returns in terms of taxes and fees, and to improve its financial accounting. This was evident in its move to introduce a value-added tax, which aimed to skim off revenues at the source, and to amend its income tax policy by expanding it to include new categories. It also presented new models of treasury bonds, including Islamic bonds, and established bodies to encourage international cooperation and obtain international loans and grants, especially European ones. It also granted local investment privileges in exchange for fixed financial deductions from profits, such as the revenues from licensing mobile phone operators in Syria.

After 2011, revenues from tax policy declined due to the war, emigration, and the loss of tax revenues from territories beyond the regime’s control. Customs duties also witnessed an unprecedented decline as the regime lost control of external border crossings, as did non-customs duties due to the decline of the service sector. There was also a decline in bond yields due to collapsing confidence in the lira and its plunging exchange rate, as well as the regime’s inability to borrow on international market due to sanctions. This forced it to rely on loans and grants, especially from Iran, which provided it with three large loans worth $1 billion, $3.6 billion (in 2013), and $1 billion (in 2015), respectively. The regime also relied less on the returns from investment concessions granted to Russia and Iran in various economic sectors, such as ports and phosphates.

After 2022, the regime began efforts to boost domestic bond yields by issuing Islamic bonds and providing credit facilities. However, these have yet to demonstrate their value. The regime has sought to build on the process of normalization with other Arab and regional countries, but this process has largely been limited to security and political issues rather than economic affairs.

6. The Syrian Economy in 2024

The Syrian economy in 2024 cannot be described as being based on a socialist approach—nor is it by any means fully capitalist. Rather, it follows a mixed economic approach, due to the lack of a clear economic strategy on the part of the regime, in addition to the war which has created a parallel shadow economy. Thus, the economy today is arranged along the following lines:

· Ownership: Patterns of ownership have shifted, with public ownership declining and state assets coming under the management of influential loyalists protected by the regime. They provide services to the benefit of the regime, by strengthening the loyalty of their own patronage networks or by providing the regime with the necessary financial support, at the expense of private ownership, which in any case is monopolized by the regime and its allies. The Assads and their extended family have continued to control vast assets, investing their fortunes through an extensive network both inside and outside the country. Public ownership of institutions with a social service nature has meanwhile declined significantly as has state support for it, in favor of other forms of ownership. As for private property, businessmen affiliated with the regime have broadened and deepened their monopolies, while a small, dispersed group is exploited for tax revenues, bearing the burdens of the country’s economic failure. Thus, the new patterns of ownership mean that the Syrian economy is essentially based on state capitalism.

· Market Patterns: The regime still relies on its oligopoly of loyalists, but this has become even more monopolistic at the expense of other competitors. Indeed, competition has become almost non-existent in Syria due to the security situation and economic sanctions. No new actor can compete freely in the market, and the regime intervenes to control certain prices—as is the case with the exchange rate of the lira, which the regime determines in advance.

· Forms of Production: There is however a little competition in the Syrian economy. The public sector has declined, with the exception of certain projects such as renewable energy, which nevertheless does not cover the bare minimum needed by its industrial cities. The private sector is suffering from enormous problems. On the other hand, the regime has moved to transform public sector companies into joint-stock companies, but has failed to meet private sector’s needs due to its own lack of capacity. Therefore, it has left the private sector with some minor scope to produce or trade, on the condition that it provides a return to the regime. Production has remained limited to a few consumer goods for local consumers. This situation has allowed a small group—regime loyalists, the ruling family, and the merchants of the Assads’ inner circle—to accumulate large fortunes, as patterns of production have moved closer to a mixed economic model.

· The form of the financial system: There has not been a major shift in this sector. The tax system remains primitive, depending on rough estimates. There is no automation to monitor profits or invoices; the banking, transfer, and electronic payment systems remain very weak. Therefore, tax returns are not a reliable source of state income, whether rates increase or decrease. The poverty that plagues Syrians living in regime-controlled areas means they are unable to pay even the most minimal taxes, with the exception of major businessmen, who pay levies under the name of taxes. Therefore, estimation and extortion dominate the tax system in Syria, meaning that taxes are used as a tool for control and security rather than financial goals.