Map of Foreign Forces in Syria, Mid-2024

Methodology

The intensity and diversity of military activities by foreign forces in Syria, the secrecy surrounding them, and with continuous changes in the scale and nature of foreign military deployments in response to the developments on the ground, regionally and internationally: all these factors make the process of tracking and classifying foreign military deployments in Syria highly complex. In order to be of value, the data gathered must be continuously updated and reviewed.

This study adopts a special methodology to count and document foreign military positions in Syria, drawing on databases that are continually updated based on monitoring by sources in the field. This data is periodically matched and re-verified with the same sources, or with information garnered from official, open-source material, for example when these deployments are disclosed as a result of their being bombed or otherwise targeted.

This process focuses solely on fixed and stable military positions, excluding the mobile or temporary outposts, barriers, and checkpoints that some of these forces use as part of their military activities—especially Iranian militias, which rely extensively on such facilities.

The military assets in this study were identified through an evaluation of the available information on the size and nature of their armaments and military assets, as well as the geographical location of each installation, without necessarily conforming strictly to military academic standards. These maps include two categories of military position: bases and outposts.

This classification defines a military base as an installation equipped with military and operational equipment and weaponry, both defensive and offensive, such as airstrips and surface-to-surface and surface-to-air missile systems, as well as special forces units for logistical support where necessary. By contrast, when a position is smaller in terms of the number of troops or types of weaponry present, it is referred to as an outpost. Due to the large amount of overlap, especially among non-state actors, this terminology has been applied to all security and military deployments excluding large-scale military bases.

These maps only denote military positions where foreign powers exercise full command. Accordingly, it does not include deployments of foreign experts, technicians, or other military personnel such as commanders and advisors at positions run by local forces, or within government institutions and the civil administration. It also excludes foreign forces whose presence amounts to less than a military outpost; thus, security checkpoints, patrols, and escort and protection details are not included.

Foreign Powers in Syria

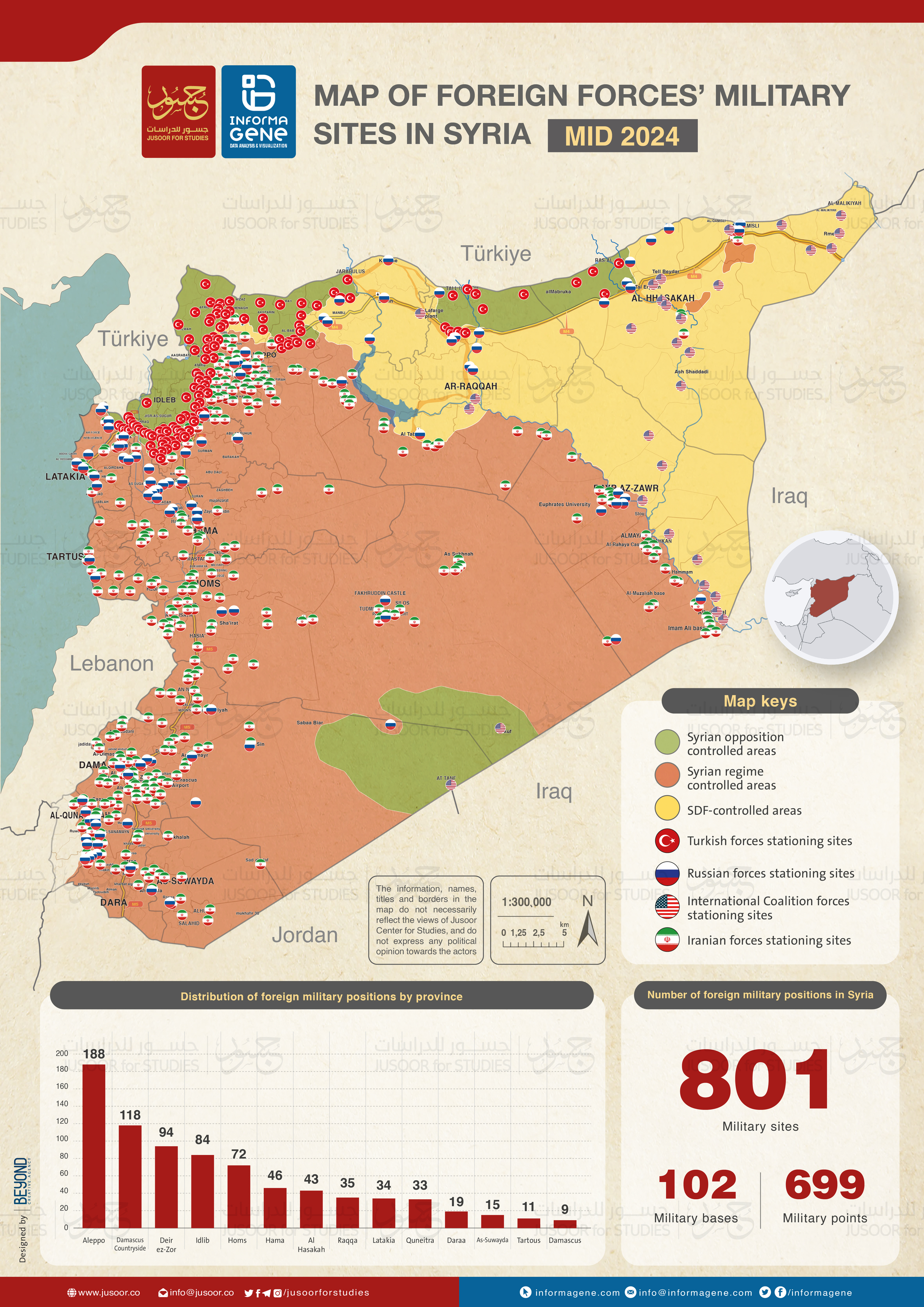

The military presence of foreign powers in Syria declined slightly over the 12 months to mid-2024, with foreign military bases and outposts decreasing numerically from 830 to 801 locations.

Foreign military positions in Syria vary greatly, both in terms of the troops and materiel present and in terms of their missions. The Global Coalition against Daesh (or simply the Global Coalition) is tasked with pursuing members of the Islamic State group and act as a deterrent force against other actors, namely Russia and Iran. Turkish forces aim protect their country’s national security against the threat stemming from the presence, activity and territorial control imposed by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) across large areas of northern and northeastern Syria. Russian forces aim to further the Kremlin’s interests at the geopolitical level, taking advantage of Syria’s geographical location, particularly its Mediterranean coastline. Finally, Iran seeks to extend and deepen its domination of the region between Tehran and Beirut, via Damascus.

Foreign powers with forces in Syria have consistently shown a desire to increase those deployments, or at least maintain their size, as an essential means to bolster their own influence in Syrian affairs and guarantee that their roles, interests, and policies are not threatened by their international rivals.

The ongoing foreign military presence in Syria and the ceasefire deal between Türkiye and Russia on March 5, 2020 have helped bring about the longest period of calm since the start of Syria’s civil war in 2011. This has essentially frozen the frontlines between local forces and their respective zones of control. However, these factors have also brought the conflict to a dead end, preventing any side from bringing about a decisive settlement of the conflict on the ground. That said, military activities are still ongoing, reflecting all sides’ determination not to abandon the quest for a military solution, but also maintaining the prospect of direct clashes between foreign forces in Syria.

Jusoor for Studies, in cooperation with data visualization platform Informagene, will continue to update and publish maps of the deployments of foreign forces in Syria as an important resources for researchers and experts.

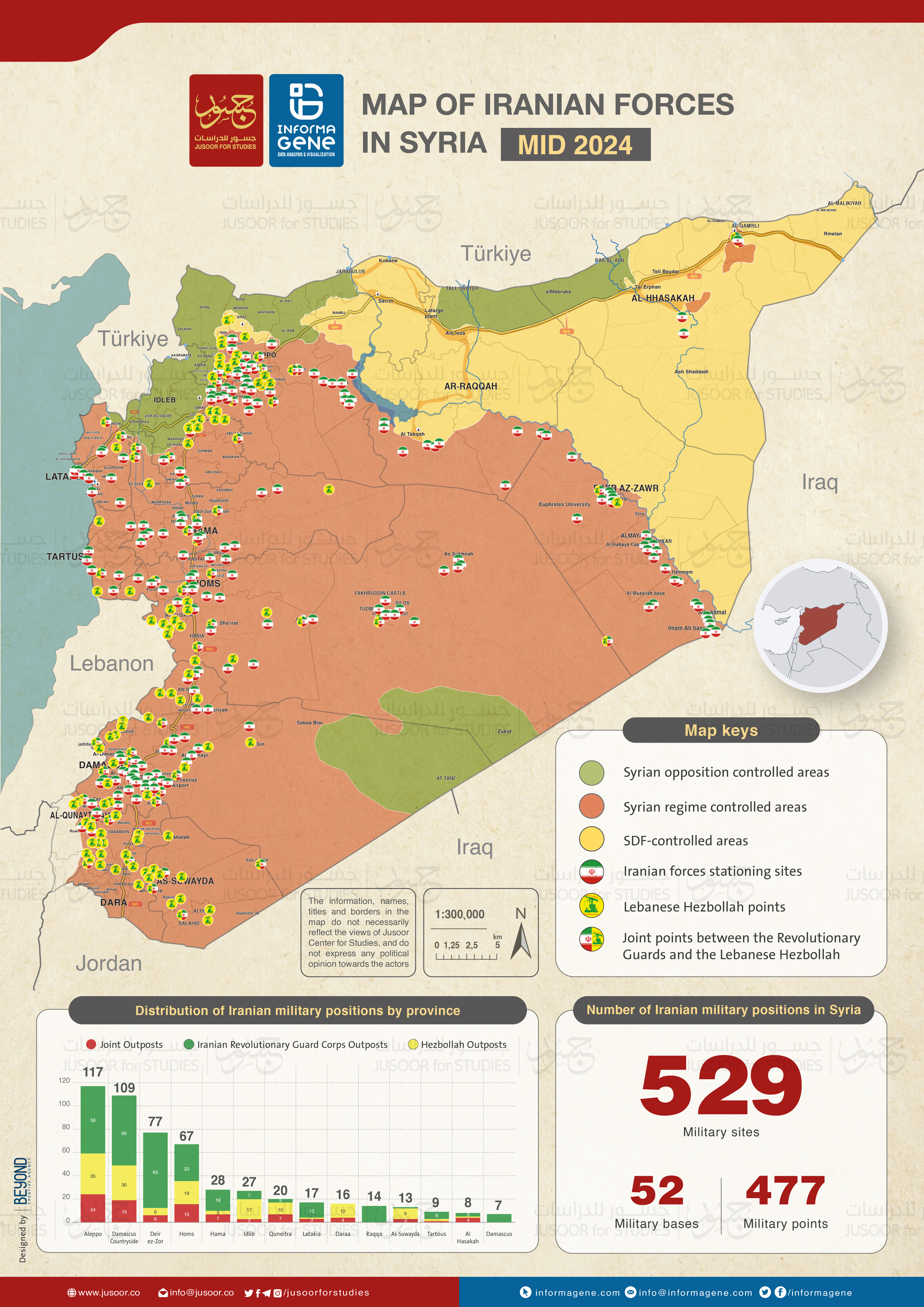

1.Iranian Deployments in Syria

Since mid-2023, the number of positions held by Iranian and Iran-backed armed groups in Syria has declined from 570 to 529, but Iran remains responsible for the largest foreign military deployment in Syria.

Iran’s military positions in Syria in mid-2024 included 52 military bases and 477 outposts, distributed as follows: 117 sites in Aleppo, 109 in the Damascus countryside, 77 in Deir ez-Zor, 67 in Homs, 28 in Hama, 27 in Idlib, 20 in Quneitra, and 17 in Latakia, 16 in Daraa, 14 in Raqqa, 13 in Suwayda, nine in Tartous, eight in Al-Hasakah and seven in municipal Damascus.

The decline in the number of Iranian positions is accounted for by redeployments away from certain less-important locations in response to escalating American and Israeli air strikes against them since the start of the war in Gaza, as well as the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)’s withdrawal from roughly 14 positions in the southwestern governorate of Quneitra, to be replaced by Russian and the Syrian regime forces. This withdrawal was likely in response to an Israeli request to Russia to ensure that these sites would not be used in any military action targeting the Israeli-occupied Golan heights, given Iran’s repeated threats to do so throughout the war on Gaza.

This redeployment did not affect the objectives and strategic value of the Islamic Republic’s military presence in Syria. Iran remains in control of the international highway cutting across Syria from the Albu Kamal border crossing with Iraq, through the Syrian desert, into the governorates of Homs and Damascus and up to the Lebanese border. Iran has also maintained a steady deployment along the frontlines with areas controlled by the armed opposition, as well as in southern Syria and along multiple drug-smuggling routes within Syria.

In general, Iranian positions fall into two main categories. The first includes the positions of Iran-backed militias that are directly commanded by the IRGC’s Quds Force and are made up of a diverse range of personnel including Syrian, Iranian, Iraqi, Afghan, and Pakistani fighters. The second category includes positions held by Lebanese movement Hezbollah and its local affiliates. These sites also operate with the support and under the supervision—directly or indirectly—of the IRGC.

Iran-backed militias have military assets across 14 Syrian governorates, making the country the most prominent foreign power in Syria. However, the majority of these sites are unable to launch military operations on their own, for several reasons, chiefly: the lack of an air force, air defense systems, or the military and logistical infrastructure necessary to carry out large-scale military operations; the continuous attrition of these forces’ combat readiness due to their repeated redeployment in order to avoid Israeli and Global Coalition air strikes; and their reliance on a mix of cross-border militias.

Iran is trying to compensate for its lack of military infrastructure by making use of the regime’s military facilities, such the 9th Division base in southern Syria, Qamishli Airport in northeastern Syria, and the 37th Brigade in Deir ez-Zor.

2.Turkish Deployments in Syria

Over the year to mid-2024, Türkiye maintained its military installations in Syria and added a single new position, bringing the number to a total of 126. These include 12 bases and 114 outposts, most of which are located in Aleppo governorate (58) and Idlib (51). Türkiye also has 10 military installations in Raqqa, four in Al-Hasakah, two in Latakia, and one in Hama.

Türkiye’s military positions are laid out in the form of lines of defense, to facilitate operations by its forces. These sites are interconnected, enabling the provision of logistical support to Turkish troops according to their different specializations: engineering, special forces, artillery, missiles, communications and signals, all supported by artillery, tanks, armored vehicles, anti-aircraft guns, and minesweepers, in addition to military communications systems.

These bases also carry out ground and aerial reconnaissance via drones, which enable them to collect information and to target regime and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) positions, as well as carrying out tasks stipulated in Türkiye’s understandings with Russia, such as joint Russian-Turkish patrols east of the Euphrates.

3. Russian Deployments in Syria

Russia stepped up its military presence in Syria between mid-2023 and mid-2024, adding nine positions to its 105 existing facilities. This marked a reversal following a drop in Russian deployments in Syria during the early months of the Ukraine war.

Russia’s military presence in Syria is comprised of 21 bases and 93 outposts: 17 in Hama, 15 in Latakia, 14 in Al-Hasakah, 13 in Quneitra, 12 in Aleppo, eight each in the Damascus countryside governorate (Rif Dimashq), Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor, six in Idlib, four in Homs, three in Daraa, and two sites each in metropolitan Damascus and in Suwayda and Tartous governorates.

The increase in the number of Russian positions over the first half of 2024 can largely be ascribed to the deployment of Russian forces at positions in Quneitra Governorate after the withdrawal of Iranian militias stationed there.

Russia had reduced its military footprint in Syria during the first year following its invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, transferring some of its Syria-based forces to Ukrainian battlefronts in order to benefit from their experience in combat operations and to redirect Russian resources towards the conflict in Ukraine. However, Russia still maintains its military superiority compared to Iranian forces in Syria, as evidenced by its deployments at new military positions in Syria since the start of 2024, and the fact that it continues to deprive Iranian forces of the opportunity to deploy in strategic locations.

Russian military sites are equipped with various types of weaponry as well as superior aerial and reconnaissance assets. Yet despite its strong weaponry and strategic deployments, Russia is seeking to integrate its ground operations with units from regime forces, Iranian militias, and Wagner mercenaries. Russia appears increasingly reluctant to risk casualties in its ranks, hence its growing reliance on mercenaries for certain operations, especially in the Syrian desert in pursuit of ISIS cells.

4. “Global Coalition Against Daesh” Deployments in Syria

The U.S.-led Global Coalition added two positions to its deployments in Syria between mid-2023 and mid-2024, bringing the total number to 32.

These positions comprise 17 bases and 15 outposts, distributed as follows: 17 in Al-Hasakah governorate, nine in Deir ez-Zor governorate, three in Raqqa Governorate, and one each in the Homs, Aleppo and Rif Dimashq governorates.

The increase is accounted for by the establishment of two new military outposts within and near Raqqa city, as part of the military and security infrastructure needed for its security and intelligence operations against IS cells in the city and its surroundings.

The Global Coalition’s troop presence is dominated by American, British, and French forces, while other members of the coalition have a symbolic presence. Denmark announced on April 22, 2023 that it was withdrawing its forces from Syria, without specifying their numbers or tasks. The coalition’s installations are equipped with a wide array of materiel, including electronic warfare systems.

The coalition forces deployed in Syria are part of the Combined Joint Task Force - Operation Inherent Resolve, a multinational military formation established by the coalition and based in Baghdad. Its current tasks are focused on advising, assisting and enabling allied forces on the ground to defeat IS. In Syria, these forces are charged with various tasks such as training and developing local allies—the SDF and the Free Syrian Army—under the supervision of military experts, as well as providing them with armored vehicles and the necessary weapons, ammunition, and logistical equipment to confront any threat from IS or Iranian militias. The coalition also supports them in combat and security missions, such as through airdrops to assist SDF in its operations against IS fighters and cells.

Officially, Global Coalition forces are present in Syria to ensure the defeat of IS and prevent it from staging a resurgence. In practice however, these forces also work directly and indirectly to prevent the Syrian regime and its allies, especially Iran, from taking control of SDF-dominated areas, where most of the coalition’s forces are stationed. The coalition sees military operations by the regime and its allies as undermining the relative stability that had been achieved by the war against IS, as well as a potential opportunity for pro-regime forces to seize control of Syria’s oil and gas resources, most of which are also concentrated close to coalition installations.

In terms of number of positions, the Global Coalition has the smallest military footprint out of any of the foreign forces present in Syria. However, it has the greatest impact, given the disparities between their respective armaments and capabilities. During the first half of 2023, the U.S. provided its forces in Syria with HIMARS multiple rocket launcher systems, citing a significant increase in Russian violations of a deconfliction mechanism and deliberate “hostile maneuvers” in areas of American operations.

Conclusion

More than four years have passed since the freezing of hostilities between various local forces in Syria brought about a state of relative calm. However, the four foreign powers deployed on Syrian soil continue to maintain and strengthen their positions, increasing their numbers according to their needs and capacities.

Each of these powers believes that the reasons for its intervention and military presence in Syria are still valid, especially as organizations and militias classified as “terrorist groups” by some or all of these forces—primarily IS, the PKK, and pro-Iranian militias—continue to be active. This situation has resulted in a state of enforced calm among local forces, largely stripping them of their ability to alter the status quo or carry out military activities outside areas they already control.

Russia has held on to all its positions in Syria, and in early 2024 occupied new positions, deploying for the first time in the Quneitra governorate adjacent to the occupied Golan Heights. This has given Russia a significant bargaining chip in any negotiations with Israel. It also continues to maintain a significant and strategically valuable military presence elsewhere, particularly on Syria’s Mediterranean coast and close to the regime’s main strategic assets and urban centers, as well as in the northeast of the country, where the bulk of Syria’s oil and gas resources are concentrated—as are the forces of the Global Coalition, meaning Russia’s presence in this area gives it a key source of leverage against the U.S. as well.

Iran, for its part, clearly seeks to maintain a heavy military presence. This is already the case across regime-held parts of Syria, but Tehran is also keen to expand its footprint whenever the opportunity arises. This stems from several motivations: ensuring the necessary cover for Iran’s security, social and ideological activities within Syrian society; accumulating as many sources of leverage as possible vis-à-vis the various other international powers present in the country; and guaranteeing continued Iranian control over the vital highway stretching from Iran to Lebanon, which allows it to coordinate the activities of its affiliated militias and support them where necessary in all the countries through which this road passes.

Türkiye continues to focus its military presence on the strip along the border between Idlib to Hasakah, passing through rural Aleppo and Raqqa provinces. This area is highly securitized, reflecting Türkiye’s goals in Syria: defending its national security and preventing the emergence of a Kurdish separatist entity on its southern border; securing that border against attacks and infiltrations by the PKK; and guarding against potential large waves of Syrian refugees by preventing further armed clashes between pro-regime and opposition forces.

U.S.-led coalition forces, in turn, are also keen to maintain their presence in Syria. While they have markedly fewer positions than other international actors in the country, these positions are mainly full-scale bases, meaning they have significant military value, enabling them to achieve its own strategic goals: monitoring the activities of IS and of Iranian militias both in Iraq and Syria, and helping implement an economic blockade against the Syrian regime by depriving it of the ability to extract and sell oil, while allowing it access to minimal quantities to meet the basic needs of the population in regime-held areas.

It is notable that the Global Coalition has deployed forces at two new positions in Raqqa Governorate, from which it had withdrawn in October 2019. This move to restore its presence in this region reflects a desire both to balance against the Russian presence there and strengthen to the military and security infrastructure the coalition needs to step up surveillance and pursuit of IS cells.

In conclusion, over the past 12 months, foreign powers have not fundamentally altered the tasks, strategic value, size, or objectives of their military deployments in Syria. Indeed, there is little indication of any such change in the near future, suggesting that the uneasy state of calm and the frozen lines of control dividing local forces are likely to remain. As things stand, any fundamental change to this situation is dependent on the decisions and military deployments of these international powers.