Initiatives to Return Syrian Refugees What have they achieved in nine months?

Introduction

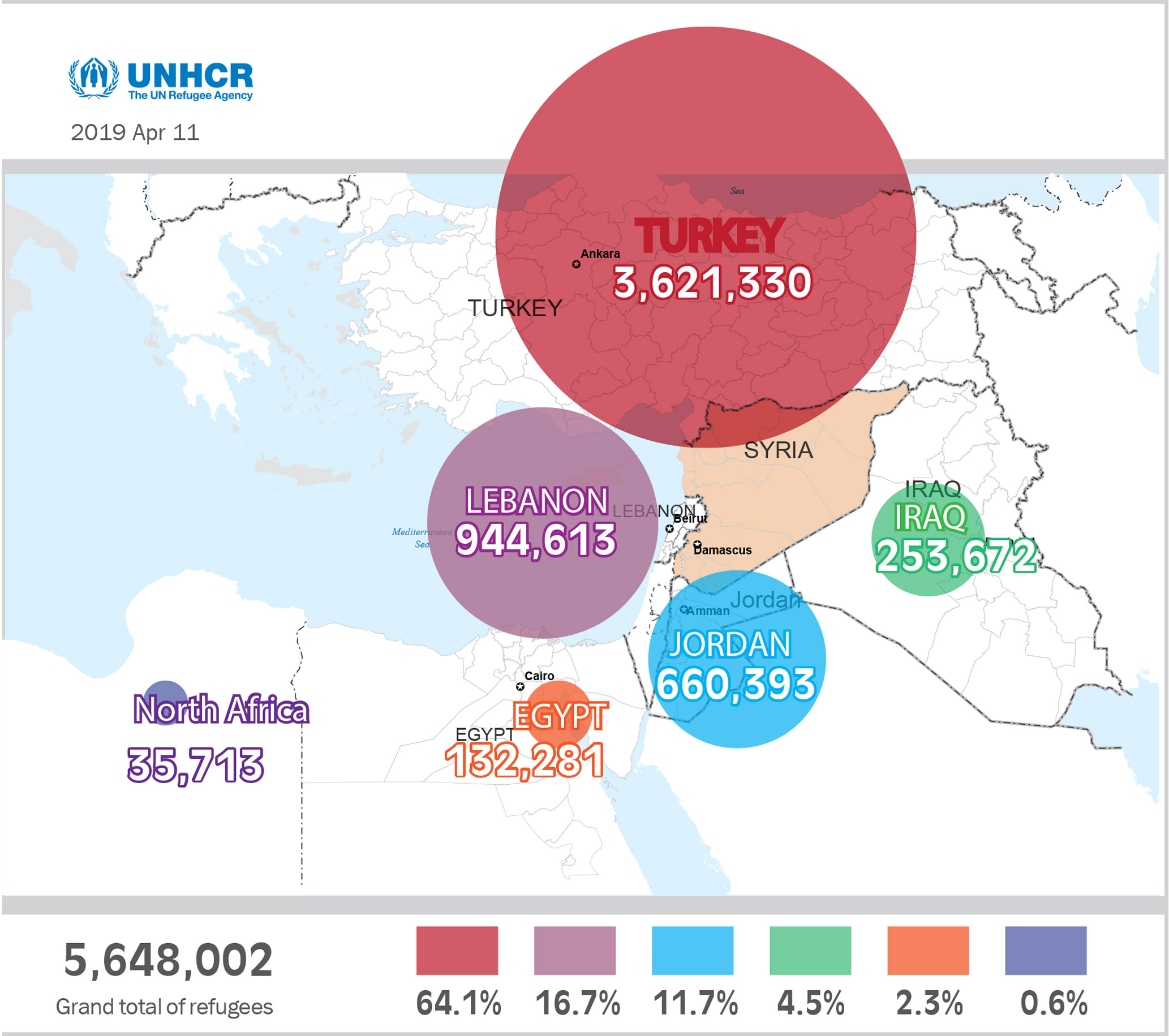

The violations witnessed in Syria since 2011, especially the army and security services’ use of severe violence, resulted in nearly half of Syria’s population, around 5.6 million refugees, fleeing the country. Of those, 65% of the refugees are in Turkey alone, and the remainder live in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt and other countries(1) .

The majority of refugees want to return to Syria at some point in time even if they refrain from doing so at present because they perceive the situation in Syria to still be too unsuitable for them to return. Many continue to live in countries of refuge in situations that are below the poverty line as this is safer than returning to Syria from which they fled or from which they were forced to flee(2).

Following the regime allies gaining complete control over the southern region of Syria in the summer of 2018, including neighborhoods within the capital and its suburbs, and the provinces of Daraa and Quneitra, Russia and the other regime allies launched initiatives in Lebanon to return the Syrian refugees there to Syria. The Russian government conducted a series of meetings and visits to various capitals to promote its initiative, and agree with the concerned governments on the mechanisms for implementing this initiative.

The Lebanese government responded positively to the proposed initiatives, especially since one of the initiatives represents one of its components and another initiative represents its security apparatus. The positive response to the initiative in Lebanon was not limited to the regime’s allies in Lebanon but extended to almost all the parties in the country, albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm and acceptance.

The Jordanian government also responded positively to the initiative and approved coordination mechanisms with the Russian side. However, Jordan emphasized that voluntary return must be guaranteed and that it is necessary to provide the objective conditions for refugees to return to their country.

Nine months have passed since the launch of these initiatives, and their effects on the ground are still modest based on the figures released by those in charge of the initiatives, even though the Russian figures are still are several times higher than the UN’s estimates.

This report discusses the process of refugee return to Syria, particularly from Jordan and Lebanon, as the returnees from these countries will move to areas under regime control. Most of the refugees in Turkey who will return, will go to the areas controlled by the opposition in the Syrian north, and therefore the objective conditions for their return are completely different.

It is necessary to mention that in recent months, some refugees from European countries have returned to regime controlled areas, but their numbers are very small and the Russian sources do not mention to them.

Figure Number (1)

Number of Syrian registered refugees according to country of asylum

First: The Size of the Phenomenon

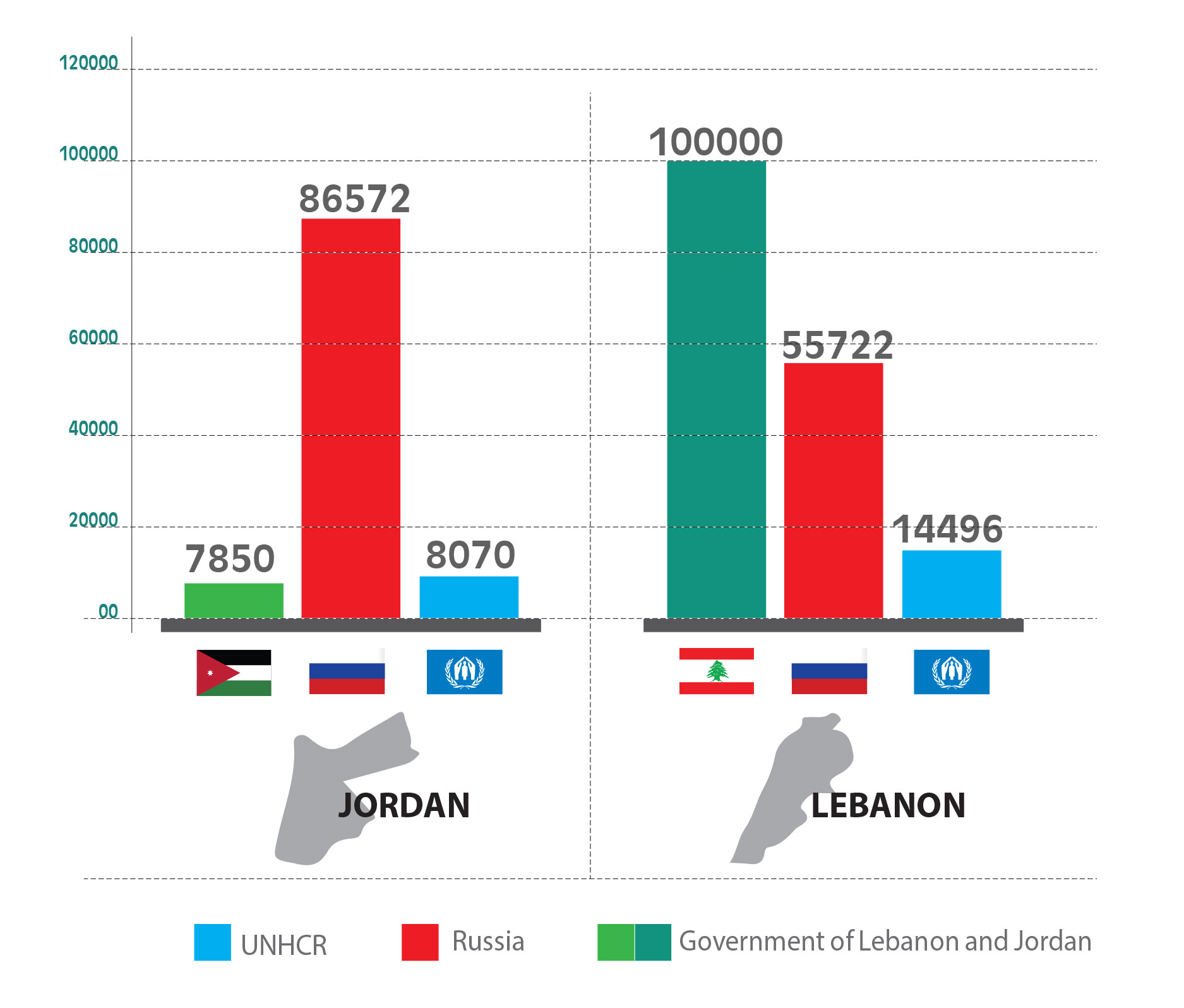

The number of Syrian refugees who have returned to Syria varies greatly depending on the source referred to. Russia and the regime’s allies in Lebanon present very high figures while the UN gives very modest figures (See Figure 2).

For the period July 2018 to March 2019, the UN estimates that 8,070 refugees returned to Syria from Jordan which is very close to the Jordanian government’s estimate. The Russian government estimated that the figure is around 87,000 refugees, more than tenfold the UN and Jordanian government’s figures. For the same time period, the UN estimated that 14,496 Syrian refugees returned from Lebanon to Syria. The Lebanese General Directorate of Security estimated that the number of returnees reached 100,000 while the Russian government estimated that figure at 55,000.

Figure 2

Number of Syrian Refugees Returning from Lebanon and Jordan

July 2018 to March 2019 (According to the source(3) )

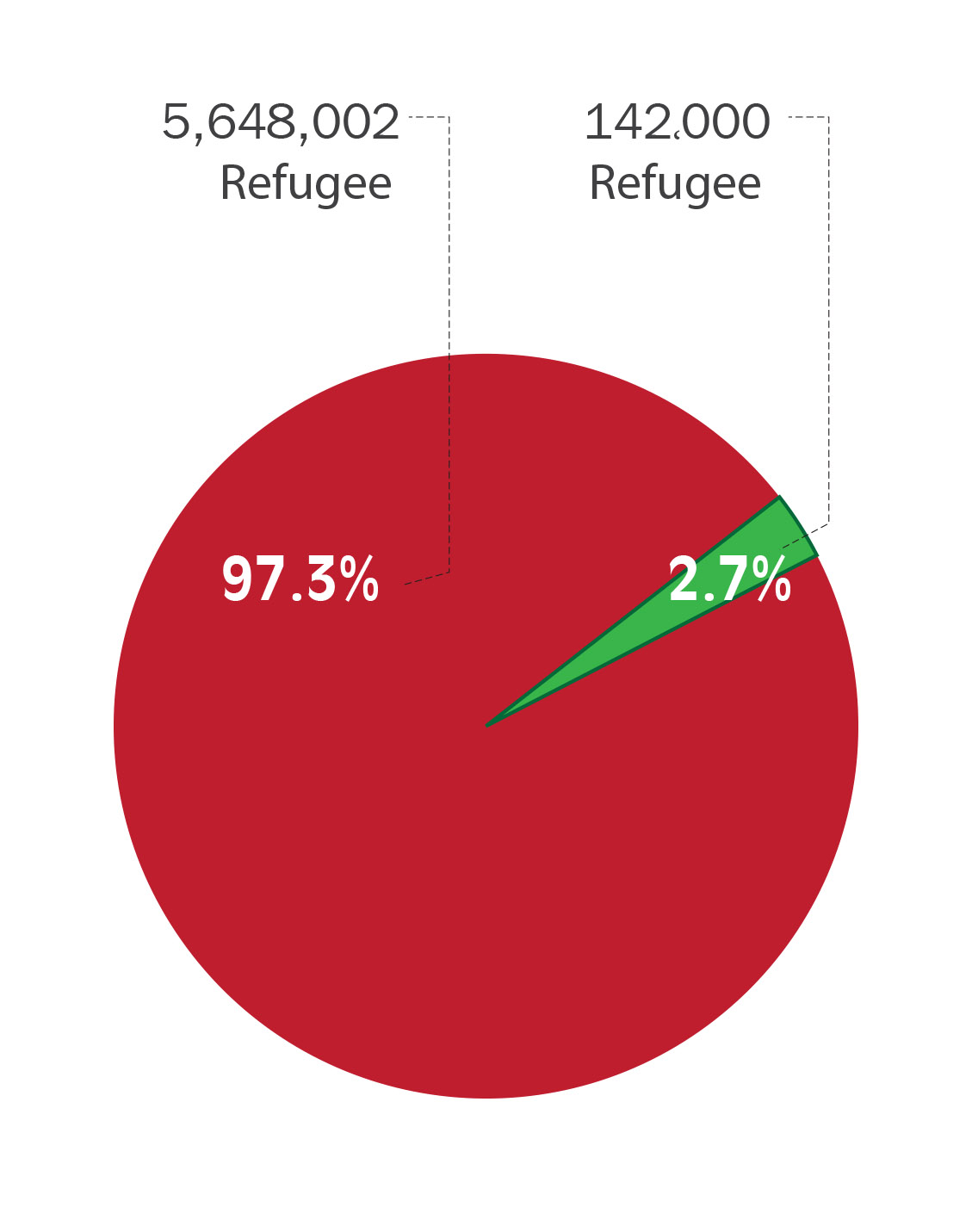

In the event the Russian data is adopted, the number of refugees returning to Syria in the past nine months is around 142,000, or around 2.7% of the total number of registered refugees as of July 18, 2018 – the day Russia launched this initiative(4) . As such, the number of returnees according to the Russian government - regardless of the accuracy of its figures- falls well below the level of the immediate expectations provided by Moscow when it launched the initiative(5) .

Figure Number (3)

The rate of refugees return since Russian announced initiative

(according to estimates by Russia)

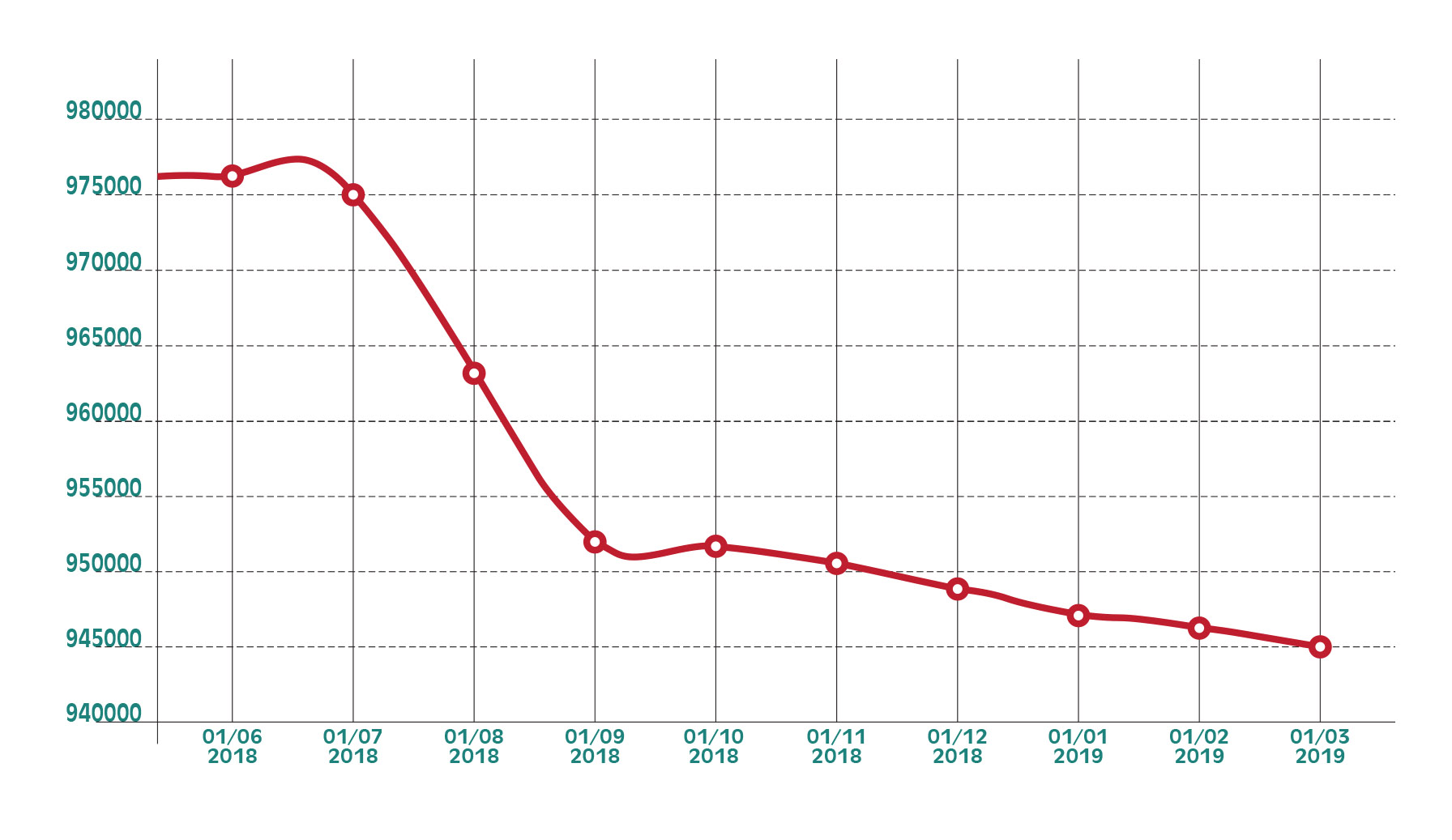

Lebanon

Lebanon hosts around 944,000 Syrian refugees, around a third of whom are living in the Bekaa region, while the remaining refugees are scattered among the province of North Lebanon, Beirut and the South. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees’ (UNHCR) records(6) since July 2018 and until now, the number of refugees in Lebanon has dropped by almost 31,000 (See Figure 4).

However, it necessary to bear in mind that this figure does not represent the number of refugees who are returning, although returnees are included in it, because the figure also includes the number of new refugees and the number of refugees who have left for third countries. In addition, UNHCR does not document the return of those who are not already registered as refugees.

Figure Number (4)(7)

The Number of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon 30/06/ 2018 – 31/03/2019

In recent years, Syrian refugees in Lebanon have had the worst asylum experiences compared to all other host countries whether neighboring or non-neighboring(8). The Lebanese government prevented them from establishing formal refugee camps, unlike other countries of refuge. This prohibition significantly limited international and local organizations’ ability to provide services to refugees. Government agencies placed pressure on and committed violations against refugees. The Lebanese government condoned speeches and practices that constituted acts of hatred and racism, especially as the most prominent of these speeches and practices came from personalities and entities that hold high positions of responsibility in the State.

The overall living conditions in Lebanon have prompted refugees to use all resources available to find alternatives, especially moving to Turkey or Europe. The situation revitalized smuggling gangs that work to exploit refugees’ suffering. According to information Jusoor Center for Studies obtained from well-informed sources in Lebanon, smuggling gangs operate in and around refugee reception offices subordinate to Hezbollah and the Lebanese General Directorate of Security. Gang members try to attract refugees to register their names to return to Syria.

Lebanese politicians constantly threaten Europeans with the arrival of Syrian refugees to Europe which is a reference to opening the door for illegal migration to Europe(9).

Jordan

Jordan hosts around 660,000 Syrian refugees. According to UNHCR records, since July 2018 until now, the number of refugees in Jordan has gone down by around 1,000 refugees only(10).

In mid-March 2019, the Jordanian Foreign Minister said that the number of Syrian refugees who have returned to Syria does not exceed 15,000 refugees(11).

At the beginning of 2019, the Syrian Embassy’s charge d’affaires in the Jordanian capital Amman said that there is an agreement among the Syrian Red Crescent, the Jordanian government and the Russian side to “secure points or centers” to facilitate the return of refugees to Syria, and that “return via the border crossings is possible for anyone who holds a valid Syrian passport, and expired passports are being extended exclusively for the purpose of return for 20 days.” The charge d’affaires noted that the embassy is receiving over 100 extension requests daily for this purpose. He added that pass documents are being issued for those who have any Syrian document for them to return within a specified period with the embassy receiving between 300-500 applications per day for this purpose. He said that for those wishing to return, including Palestinians normally resident in Syria, it is not necessary for them to renew their passports(12).

Second: Why are Refugees Not Returning?

Despite refugees’ difficult living conditions, especially in Lebanon and in the camps in the remaining countries of asylum, the quantitative data, even that provided by the Russian side and pro-regime Lebanese parties, shows a limited and timid response to calls for refugees to return to Syria. This response raises serious questions about why almost all refugees prefer to continue living in miserable conditions in countries of asylum, especially in Lebanon, rather than return to the areas under regime control in Syria.

To answer this question, it is necessary to emphasize that issues of a humanitarian nature, such as asylum, have complex dimensions, and, therefore, the issue cannot be attributed to a particular motive or motivations that justify a whole group’s mode of behavior. The issue differs from person to person or from one family to another, based on each’s circumstances in Syria and in the country of refuge.

By reviewing UN reports concerning this issue and based on interviews conducted by Jusour Center for Studies with senior UN officials in Jordan and Lebanon, the following reasons were identified as the most important reasons preventing refugees from returning:

1) Security Concerns

Many refugees have concerns about what the Syrian security services may do to them after they return, especially in the absence of guarantees from regime allies. This is a major reason preventing refugees from returning. The Syrian security services have arrested several refugees returning to Syria, some of whom have disappeared in regimes prisons, while others were killed while in detention. Although it is assumed that there will be no security claims against voluntary returnees, the regime deals with all those who left Syrian territory on the basis that their leaving the country is a charge that justifies holding them accountable (13).

For the period January 2017 until March 2019, the Syrian Human Rights Network documented at least 1,846 cases of returnees who were detained by the Syrian regime forces. Among those who returned and were detained during this time period, the Network documented 13 cases of detained returnees dying under torture.

2) Pre-Security Review

The Syrian regime adopted a policy of issuing “pre-entry visas” for Syrians wishing to return to Syria. Those wishing to return from Lebanon must register their names with Hezbollah centers or Directorate General of Security centers (controlled by the regime's allies in Lebanon). The names of those who registered are then sent to Damascus for security review. Based on the security review, applicants are granted or refused permission to enter Syria.

According to the Minister of Social Affairs in Lebanon, until March 2019, the Syrian regime has approved only 20% of the lists of Syrians wishing to return(14).

3) Economic and living conditions

Syria’s current economic situation is a major obstacle to the return of refugees to Syria(15). The war conditions have led to the collapse of most labor sectors in Syria, unemployment rate increased significantly and the class gap widened dramatically(16). In addition to other factors that would led youth in any country - even if they have not experienced a war - to seek ways to migrate from the country rather than return to it.

4) Mandatory Military Service

Historically, the mandatory military service in the Syrian army for males has been a burden on the youth, and they tried - even before 2011 - to evade serving by any means possible. The military operations in Syria since 2011 have increased youth’s desire to avoid the mandatory military service. This desire is almost equal among supporters and opponents of the regime.

In recent years, escaping the mandatory military service originally constituted a major motivation for many Syrians to flee Syria with the aim of preserving their children’s lives and preventing them from participating in the killings carried out by the Syrian army. This motivation contributed to gangs forming within the regime’s establishment to transfer young men called up for mandatory service to neighboring countries in exchange for large bribes.

With the continuation of the mandatory military and reserve service, and the existence of legal claims against those who abscond from service, all families with a male member of mandatory military service age or with youths who are about to enter this age, will refrain from returning until further notice.

5) Absence of incentives

The Russian initiative and other initiatives lack any incentives for returnees, whether those incentives are security guarantees that returnees will not be prosecuted or even postponing the mandatory military service for those who are wanted for service. In addition to the lack of material incentives that would enable impoverished refugees to secure their livelihoods after returning, especially as many of the refugees did not own any property before they migrated or lost their property during the war(17) .

Some European countries have adopted incentives to motivate refugees to return to their countries voluntarily. In 2018, Germany adopted an incentive system whereby the state pays each asylum seeker up to 1,000 Euros to return to their country and up to 3,000 Euros for returning families(18).

Third: Does the Regime and its Allies want Refugees to Return?

The issue of refugee return is absent in the regime’s political literature, and it is only mentioned in passing in certain contexts. In this regard, the regime’s position appears to result from pressures from its allies rather than being a self-motivated policy. The regime is closer to its Iranian ally in this matter as Iran, also, does not discuss the issue of refugees returning and it does not participate in any initiative focused on this issue.

On the other hand, the regime’s allies in Lebanon, Hezbollah and the Free Patriotic Movement, are calling for the return of Syrian refugees. This issue appears in the political literature of both parties, especially the Free Patriotic Movement’s, which adopts a discourse that often borders on hatred and racism.

Since the summer of 2018, Hezbollah adopted its own initiative to return refugees. On July 4, 2018, Hezbollah announced the launch of a program for the repatriation of refugees wishing to return to Syria. The party opened its own centers to receive refugee requests in Baalbek, Hermel, Laboueh, Bednayel, Dahieh (southern suburb of Beirut), Nabatieh, Tyre, Bint Jbeil and al-Adaisa(19).

In this regard, Hezbollah’s position is more consistent with the Lebanese political reality than with its Iranian supporters’ position or the position of its ally in Damascus. The presence of Syrian refugees is a vital issue in the conflicting party scene in Lebanon. Hezbollah cannot ignore this issue, especially as it is directly responsible, in many cases, for the displacement of tens of thousands of refugees who are now in Lebanon. The party continues to control some of the areas in Syria from which is home to some of the refugees in Lebanon such as al-Qusayr(20).

Russia has shown a strong desire to return refugees to Syria and this issue appears regularly in its political discourse. Russia launched its own repatriation initiative in July 2018. In the same month, it announced the establishment of special centers in Syria to receive, allocate and shelter internally displaced persons and Syrian refugees. Russia said that these centers can host around 336,000 refugees, and they are distributed in several provinces including Damascus Suburb, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, Deir Ez Zor and Eastern Qalamoun(21).

However, the Syrian regime’s continued violations against returnees, including arbitrary arrests and killings them under torture, its policy of “issuing visa-entries” for those wishing to return from Lebanon, among its other policies, raise questions about the seriousness of the Russian position. Since its intervention in Syria at the end of 2015, Russia has shown its absolute power to impose decisions of war and peace, even on its Iranian allies. More importantly, Russia is able to impose suitable conditions for the return of refugees and force the regime to abide by them such as preventing the Syrian security apparatuses from entering the areas it oversees, just as it forced the head of the regime not to approach President Putin’s platform.

However, Russia, Iran, the regime and their remaining allies, have no direct interest in the return of refugees. On the contrary, the survival of these refugees outside Syria helps the Iranians and the regime to stabilize their plans for demographic change in the country. It also decreases the security pressure that returnees from destroyed areas would pose, especially as those returning will not in the best of circumstance be regime supporters.

With regards to the refugee file, the dilemma Moscow, in particular, faces is that the file has become a Western pressure card, and one of the main obstacles to reaching a final political solution, and consequently, initiating the reconstruction process which Moscow and its allies do not have the capacity to finance. Through its refugee repatriation initiative, Moscow is trying to achieve a breakthrough in this file whereby a proportion of the refugees who are not considered a security problem are absorbed and the refugee crisis is resolved in neighboring countries, at least. Russia seeks to appear as the side taking responsibility for returning refugees while Western countries are perceived as blocking this endeavor.

Conclusion

Many of the refugees who left Syria did not participate in any opposition or pro-regime activities, and they fled as a result of their fear for their lives, especially as the regime randomly used tools of death against civilians without discriminating based on political position. Many of these refugees have a desire to return to Syria, especially those living difficult lives in the countries of refuge (especially in Lebanon) and those who have no hope of resettling to another country.

The shy figures of returnees since Russia launched its initiative, and its Lebanese counter-parts launched theirs, point to the failure of Russian policy to achieve its goals, even its media objectives. Moscow needs to think of a new methodology that addresses the challenges that prevented refugees from responding to the return initiatives and which offers solutions and guarantees rather than just accusing the West of impeding the return of refugees.

The international community should continue to provide support to refugees, enabling UNHCR and other international organizations to deliver humanitarian assistance to them, and to ensure minimum living requirements that enable refugees to decide whether to return to Syria or not. “Voluntary return” should not be a mandatory choice without a viable alternative.

The international community should pressure the regime and its allies to provide security guarantors for returnees, and enable the UN to monitor their situation and ensure their safety. However, the main responsibility before the international community is to push for a comprehensive political solution that guarantees the rights of all Syrians and allows them to live in dignity within their own state. This is the solution that will promote most return refugees to return, even without initiatives or incentives.

The initiatives to return refugees to Syria without a comprehensive political solution that includes actual changes in the structure of the security system and without international and local guarantees, represent a push for the Syrians to return to the regime prison, and consecrates the crimes and violations that have taken place from the beginning and future violations.

Initiatives that avoid dealing with refugees’ legitimate rights to return to their places of origin, compensate them for damages to their property, and discriminate among refugees based on sect (e.g. preventing people from Qalamoun from returning to their homes despite the security calm in their areas) represents an escape from the immediate crisis towards a future explosion.

Footnotes:

1- Operational Portal Refugees Situation, UNHCR

2- Based on a survey conducted by the UNHCR in 2018, 76% of Syrian refugees hope to return to Syria at some point in time in the future, but 85% of those who participated in the survey said they do not want to return in the following year: Regional RPIS in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon (Round IV), UNHCR, July 2018

3- ‘The Displacement Dilemma: Should Europe help Syrian Refugees Return Home?’ The European Council on Foreign Relations, March 2019, p.4

4- Operational Portal Refugee Situation, UNHCR

5- Russian Defense: Around 200,000 refugees may return to Syria in the near future, Sputnik, 24/07/2018

6- Operational Portal Refugee Situation, UNHCR

7- Operational Portal Refugee Situation, UNHCR

8- Hundreds of UN and national reports documented the violations and the difficult circumstances Syrian refugees in Lebanon experienced since 2011 until the present. For example, see ‘Unpacking Return: Syrian Refugees’ Conditions and Concerns,’ Sawa for Development and Aid, February 2019

9- For example, see the statements of Lebanese President Michel Aoun during his visit to Moscow in March 2019: ‘Lebanon warns Europe could face another ‘wave’ of Syrian refugees’, The Independent, 27/03/2019

10- Operational Portal Refugees Situation, UNHCR

11- The Jordanian Foreign Minister: ‘The Return of Syrian Refugees Requires Providing Peace and Stability,’ The New Arab, 14/03/2019

12- ‘Fate of Syrian Refugees in Jordan… Between Return or Remaining,’ CNN Arabic, 05/01/2019

13- ‘Syria’s Returning Refugees,’ Foreign Policy, 06/02/2019

14- Kouyoumjian: The Al-Assad Regime Hinders the Return of Refugees and No Money to Rebuild Syria before a Political Solution, Independent Arabia, 22/03/2019

15- ‘The Displacement Dilemma: Should Europe help Syrian Refugees return home?,’ The European Council on Foreign Relations, March 2019, p4

16- Syria’s War Economy Exacerbates Divide Between Rich and Poor, Middle East Institute, 06/11/2018

17- A UNHCR survey conducted in 2018 among Syrian refugees showed that 65% of the refugees who do not want to return to Syria are among those whose houses were destroyed. In contract, 47% of those who want to return in the following year, have property in Syria. See ‘Regional RPIS in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon (Round IV)’, UNHCR, July 2018

18- Germany offers year of rent to asylum seekers who return home, Euronews, 27/11/2018

19- ‘Sputnik’ reveals Hezbollah’s mechanism to return Syrian refugees to their country, Sputnik, 04/07/2018

20- ‘No One can Guarantee our Safety’: Syrians Stuck in Squalid Exile, The Independent, 22/01/2019

21- Russia Establishes in Syria Centers to Receive, Distribute and Shelter Refugees, Russia Today, 18/07/2018