Power in the Shadows: Syria’s Fourth Division

Introduction

In the wake of Syria’s 2011 uprising, many of the regime’s military forces declined in strength. One major exception was the Fourth Division, which has remained battle-ready and able to field some 18,000 personnel, including officers, non-commissioned officers (NCOs), and enlisted soldiers.

The Fourth Division was established in the 1980s from the remains of the Defense Companies, led by then-president Hafez al-Assad’s brother Rifaat, who had lunched a failed coup attempt in 1984. The Defense Companies’ main units—the 40 th and 41 st battalions—had their names changed, officers loyal to Rifaat were dismissed, new brigades and regiments were established, and the president appointed his son Maher to the force, tasked with beefing up its ranks. Maher al-Assad commanded the division’s 42 nd battalion until 2018, when he became overall commander of the Fourth Division under a decree by his brother, current President Bashar al-Assad. This has given the division access to exceptional material, military and security capabilities and far-reaching decision-making powers.

1. The Fourth Division’s Structure

The Fourth Division operates separately from the First, Second and Third divisions. However, along with the First Division (deployed in Al-Kiswah, south of Damascus), and the 3 rd Division (based in al-Qatifa, northeast of the capital), it forms what is known as the General Command Reserve Corps.

The Fourth Division currently consists of the following entities: The commander and his deputy, Division staff, a Chief of Operations, a Security Office, four brigades, and three regiments, along with several independent battalions such as the al-Sataa battalion, the suicide battalion, an anti-tank battalion, and a military police company.

Regiments

The Fourth Division has three reinforced regiments: The 555 th Special Forces (Airborne) Regiment, the 999 th Rapid Intervention Regiment, and the 154 th Artillery Regiment.

These regiments are as well-endowed with equipment and manpower as the Fourth Division’s other brigades (see below). Maher al-Assad has sought to have them serve as support forces for the brigade he commanded prior to 2018, in an attempt to circumvent official organizational structures and staffing procedures.

The regiments include:

· The 154 th Artillery Regiment.

· The 555 th Special Forces (Airborne) Regiment, which commands the following battalions: 584 th Airborne Battalion, 585 th Airborne Battalion, 586 th Airborne Battalion, 183 rd Artillery Battalion, and an anti-tank battalion.

· The 999 th Rapid Intervention Regiment, formed after 2011, is mainly deployed in Damascus, Daraa, and Deir ez-Zor, alongside Iranian militias. It operates under a grouping system.

Brigades

The Division has four reinforced brigades: The 138 th Mechanized Brigade and the 40 th , 41 st and 42 nd Tank Brigades. These brigades are equipped with the most cutting-edge weaponry and equipment of any Syrian regime force.

· The 138th Mechanized Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Ahmad Khallouf, was tasked in 2011 with suppressing protests in Zamalka, Daraya, and Douma. It was one of the most brutally effective forces in Homs: Major General Jamal Suleiman was tasked with commanding operations in the central region, and committed crimes on a vast scale in the Homs city neighborhoods of Baba Amr, Khalidiyah, Bayyadha, and the villages of Tal Kalakh and Houla, in the wider Homs province.

· The 40 th Tank Brigade.

· The 41 st Tank Brigade. This detachment has operated in the Damascus countryside, especially Zabadani, Sarghaya, Madaya, Deir Qanoun, Burayha, Rankous, Asal al-Ward, Talfita, Hafir, Douma, Daraya and the Quneitra countryside. It took part in the siege of Daraya, and is accused of massacring 700 people in the district in 2012.

· The 42 nd Tank Brigade, which was commanded by Maher al-Assad until he was appointed overall commander of the Fourth Division in 2018.

Security Office

The Fourth Division has a dedicated Security Office, headed by its best-known commander Brigadier General Ghassan Bilal. His subordinates include Colonel Hussein Mreisha, Lieutenant Colonel Yasser Salhab, Major Ahmad Khair Bayk, a group of Non-Commissioned Officers, investigators, and a guard company. The office is structurally divided into several departments, including a monitoring and investigations section, prison, guard, recruitment, and checkpoints sections, and an economic department.

The Division’s hierarchy and organizational structure have evolved since 2011, with the creation of several new regular and irregular units, and the bolstering of its core combat units to adapt to its new military, security, and economic role.

2. Fourth Division Deployments

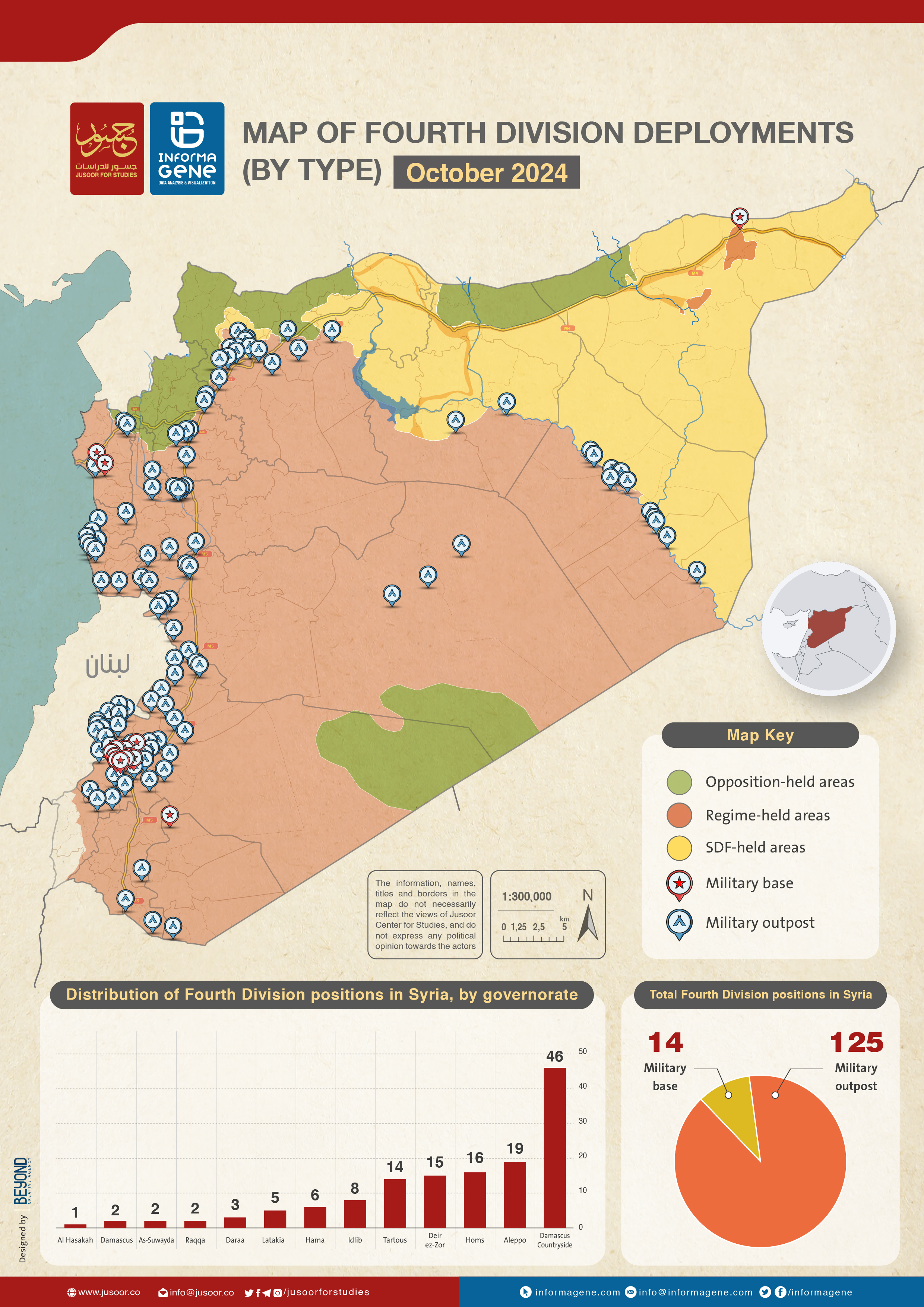

Fourth Division forces are deployed in every governorate within the regime-controlled part of Syria, particularly Rif Dimashq, Tartus, Deir Ezzor, Hama, and Aleppo governorates. Jusoor for Studies has identified approximately 140 positions belonging to the Division.

These include command and control bases, subordinate and operational command posts, and military bases, in addition to operations units, checkpoints and administrative departments for crossings, which are responsible for various military, operational, security, and economic tasks. These positions are distributed as follows: 46 in Rif Dimashq, 19 in Aleppo, 17 in Homs, 15 in Deir Ezzor, 14 in Tartus, eight in Idlib, six in Hama, five in Latakia, three in Daraa, two each in Sweida, Raqqa and Damascus, and one in Hasakah. None were recorded in Quneitra.

The Fourth Division has approximately 75 bases for operational and sub-operational command and management of combat units, 26 land crossings at borders and frontlines, and a presence at seven military and civilian airports, as well as 65 major checkpoints throughout the country.

The Fourth Division shares 18 positions with other regime security and military units, notably the Military Security agency, which provides it with considerable support, as most of its senior officers have served on the division’s staff and are particularly loyal to Maher al-Assad.

The Fourth Division has at least 75 military and security missions throughout the country. It also manages security and economic security operations via 50 detachments, mostly in Rif Dimashq, Homs, Aleppo, and Deir Ezzor.

While the division is deployed in various areas, it focuses its activity and presence along the lines of contact with opposition factions in the northwest of the country and its border regions, especially close to the southern border with Jordan and on the frontier with Lebanon, where it controls and profits from ports and shipping routes, imposing escort fees on traders in order to fill its coffers.

3. Roles of the Fourth Division

Military

The Fourth Division’s main combat mission has been to act as the ninth line of defense for the capital, Damascus, after the Republican Guard, which is charged with the first eight. The nature of this mission became clear after 2011, as the Division used every form of violence and force to protect the outskirts of the capital from opposition forces. It committed widespread atrocities against civilians in cities and towns that revolted against the regime, including Daraya, Muadamiyat al-Sham, al-Zabadani, and Serghaya.

As Syria plunged into civil war, the Division took on major combat missions, deploying across a wide geography and becoming the only military force to be active in every province. It took on the role of overseeing military operations coordinating with other forces. This shift was particularly notable as the regime’s General Staff came to play second fiddle to regional operations rooms run by the Fourth Division, due to Maher al-Assad’s influence over field commanders assigned from the Fourth Division to other units.

Maher al-Assad has exclusive control over decisions within the Fourth Division, which are implemented by brigade and operations commanders, along with the head of the Security Office. He has adopted a policy of securing absolute loyalty through policies of intimidation and inducement. For example, officers who achieve top grades in military training courses are rewarded with gifts of cars, while those who do not achieve such grades are punished. This has prompted many officers to use heavy-handed tactics with the directors of military colleges to ensure they are given top grades.

The Fourth Division has long enjoyed extensive powers within the military establishment, and continues to do so. This includes the selection of military personnel, from recruitment centers in Aleppo and Damascus, as well as carrying out specialized training in skills such as parachuting, monitoring officers during training courses, selecting the best students for transfer into the Fourth Division, and providing the Division, which is armed like a reinforced brigade, with modern tanks and equipment.

The Fourth Division enjoys absolute authority to intervene in any military matter. Maher al-Assad has powers to access the results of surveys of morale in regime forces before they are presented to the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and discussed by the Military Party Committee, of which the Minister of Defense are chair and deputy chair. These surveys aim to measure of the morale of all three sections of the military, through a paper questionnaire distributed by political administration committees.

The Fourth Division has special powers that prevent other military or security forces from violating its jurisdiction. For example, it issued a circular in May 2024 prohibiting other entities from detaining its personnel, except under orders issued by the Fourth Division’s Security Office or the Military Police Company, itself affiliated with the Division. This directive had been in effect before 2011, but it was reissued and implemented in 2024, a move by Maher al-Assad following his brother Bashar’s announcement of a series of changes in the country’s security leadership and plans to restructure the security services. Maher’s directive was a reminder to the new leadership that his division remains above all accountability.

Prior to 2011, the Fourth Division had more than 18,000 personnel, but as the Syrian civil war unfolded, this number fell due to battlefield losses and desertions. This prompted the brigade to recruit new forces to fill the gaps. It did this through volunteer announcements issued by its Security Office, headed by Ghassan Bilal, drawing on armed groups from beyond Syria’s official armed forces. It began by forming and assigning officers to local militias, such as the Assad al-Ghouta Forces (The al-Ghayth Forces) led by Brigadier General Ghiyath Dalla and Major Mohannad Ghanem. Recruitment to these militias was particularly effective in border areas that were a focal point for volunteer advertisements, such as Yabroud, Jarajir, and Assal al-Ward. Unusually, they offered recruits a system of 10 days on duty and 5 days off, and deployment within their own localities.

Under the Division’s contract system, once recruits have undergone a short military training course, sometimes as brief as one month, they are assigned to smuggling and escorting tasks. The force strives to win over and recruit residents of the areas where it operates, particularly through financial incentives funded by its smuggling operations. It also uses intermediaries. For example, in late 2022, it restructured its Security Office in the Qalamoun region of rural Damascus, appointing a former member of the People’s Assembly, Muhammad Abdo Asaad, to form, deploy and command its forces in region again, after the dismissal of its previous commander, Abu Hamza al-Halabi.

Meanwhile, the Fourth Division has maintained its primary mission as the ninth ring of defense around the capital and the presidential palace, as well as taking on additional tasks including working alongside the General Staff in leading combat operations and coordinating with other forces, such as Iranian militias and Hezbollah.

The Security Role

The Fourth Division had a role in Syria’s security system prior to 2011, through its Security Office, which provided protection for Maher al-Assad and his senior officers, secured the division’s military facilities and offered special protection to traders affiliated to its commander. It was also charged with monitoring and gathering intelligence on senior officers, chiefs of military brigades, and senior security officials.

Thus, the Fourth Division cannot be viewed solely as a military formation. Rather, it constitutes an economic and security entity within the state. While Hafez al-Assad passed his political power to his son Bashar, he bequeathed his other son Maher a military division that affords him influence in the worlds of finance, business, and the cross-border trade in contraband.

The brigade constituted the regime’s strike force against any major security threat. It was responsible for crushing Kurdish demonstrations in Aleppo and Hasakah in 2004 and 2007, and undertook secretive special missions for the presidential palace. It is suspected of involvement, alongside Hezbollah, in the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005.

Its role expanded further after 2011, as it became the regime’s main tool of repression against anti-government protests and then the armed opposition. Maher al-Assad exploited the regime’s need for special forces to tackle the armed opposition, expanding his unit’s role and influence both as a security and a militarily asset, deploying across the country.

Maher has positioned his brigade as a parallel system that controls various aspects of the new shadow economy which emerged after 2011. It is the Fourth Brigade that delineates the boundaries of this economy, determining the locations of crossings and trade routes, the types of goods traded and in what volume. The division has expanded the role and influence of its Security Office to form an independent, specialized agency that oversees investigation and documentation offices, private prisons, and more than 50 checkpoints. It receives reports from all the regime’s security branches and military units, and submits them to Maher al-Assad. The Security Office also manages all of Syria’s Captagon factories, and oversees the transportation and export of the drug.

The division does not limit itself to monitoring officers from other military units through the Security Office, but also monitors non-affiliated local militias by assigning its own officers to lead or supervise them, leaning on its connections with military security agencies.

Finally, the Security Office helps protect the Fourth Division’s interests and influence. It has seized significant powers that were previously in the hands of the presidential palace and its associated security committees, such as opening and managing crossings on frontlines and external borders. Moreover, Fourth Division personnel have deployed alongside Republican Guard forces, as well as at all locations where Iranian militias and Hezbollah are present in Syria, cooperating with them in military operations, facilitating their movement and transfers of equipment, and partnering with them in drug trafficking and human smuggling. Conversely, the Security Office, through its close relationship with these militias, monitors and tracks their activities and personnel, providing periodic reports about them to Maher al-Assad.

The Economic Role

From its establishment until 2011, the Fourth Division primarily drew its funding from the regime’s budget for the Ministry of Defense, like other army divisions. However, based on orders from the top of the regime, it received more funding than other military divisions—a dynamic that was reflected in the nature of the equipment, food supplies, and military and logistical materials it received, which were superior to those of other divisions. Additionally, it benefited from greater funding for military housing projects than other divisions, and its senior officers generated resources from various forms of corruption, including their involvement in smuggling operations along the Lebanese border.

From 2011 onwards, the Syrian economy and the regime’s finances began to deteriorate, due to the increasing costs of military operations and the imposition of international economic sanctions, which made it harder for the regime to pay and equip its forces. This prompted it to allow certain military units—especially the Fourth Division, seen as highly loyal given Maher al-Assad’s presence—to seek new sources of income.

Accordingly, the leadership of the Fourth Division and its Security Office turned to various illegal activities. As well as imposing royalties at the many crossings it manages, both internally and on Syria’s borders with Jordan and Lebanon, it has engaged in looting homes, drug trafficking, smuggling commercial goods and foodstuffs, human trafficking across frontlines and borders, and generally contributing to the creation of a shadow economy.

1. Looting

In contrast to other military units, the brigade has adopted a decentralized strategy for generating income, beyond the central funding it receives from the Ministry of Defense. Its members and leaders have been allowed to loot homes in the cities and villages they whose residents they have displaced, in areas including Homs, Damascus and Rif Dimashq provinces, Daraa, and elsewhere. This has allowed to generate financial returns, including by directly selling stolen furniture at low prices in designated markets, such as markets in the neighborhoods of Al-Nuzha, Al-Zahra, and Akramah in Homs city. [1] It has also looted entire commercial markets, such as the City Center complex in Jourat al-Shiyah in Homs. [2] In the same manner, it looted various cities and districts of Damascus and Rif Dimashq, [3] selling the stolen goods in the markets of Mezzeh, Jisr al-Thawra, and the Douylaa in the Kashkoul neighborhood and the Soumariyyeh Garage markets.

The Fourth Division has also made deals with individuals who provide financial support, food, and logistical supplies in exchange for a share of looted goods once the force has entered and plundered a certain area. Examples include agreements in Homs with former members of the People’s Assembly such as Firas Al-Saloum and Shahada Kamel Mayhoub. [4]

2. “Escorting” and Extortion

The brigade has exploited its presence across the country to turn escorting and extortion into primary sources of income. It has collected tolls at roadblocks, military checkpoints, and crossings between areas controlled by various groups, whether the armed opposition or the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). For example, it has escorted trucks of smuggled foreign tobacco from Mediterranean ports to other provinces, and accompanied traders transporting goods from various cities to different regions in exchange for financial returns and protection at the checkpoints of other brigades, as well as from security agencies that could seize and steal these goods. [5]

The Fourth Division has entrusted the management of these operations to non-military figures such as Abu Ali Khadr (or Khodr), [6] a Syrian businessman who was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department under Executive Order 13582 [7] for acting as an intermediary and contractor for the Division. In 2017, Khadr established the “Al-Qalaa Security and Protection Company,” which employs Fourth Division personnel to provide protection to convoys, as well as collecting fees and facilitating smuggling at checkpoints and internal crossings. It does so in several regions, including between regime and opposition areas in Atarib and Abu al-Zandain, internal crossings between the regime and the SDF such as Al-Hawra near Raqqa, and at external crossings and smuggling conduits with Lebanon and Jordan.

3. Drugs, Smuggling and Human Trafficking

The Fourth Division has seized control of the drug trade in Syria, notably of the amphetamine Captagon, of which it supervises the production, storage, distribution, transportation, and export to the Arab Gulf countries, raising billions of dollars. [8] It has leveraged military and security relations with pre-existing drug production and smuggling networks to serve its own interests, expanding these operations, [9] and developing new smuggling methods using drones, hot air balloons, and vegetable and fruit trucks, as well as smugglers crossing via illegal cross-border routes controlled by the Division. [10]

These operations are led by figures loyal to Maher al-Assad, such as Khaled Qaddour, a Syrian businessman also subject to U.S. sanctions under Executive Order 13572, who is a key figure responsible for laundering the proceeds from smuggling. Another key figure is Samer Kamal al-Assad, Maher’s cousin, who is subject to U.S. sanctions under Executive Order 13582, [11] for his role in the production of Captagon pills in the Qalamoun region.

The brigade has not limited itself to smuggling narcotics. It has also engaged in illicit exports of everything from agricultural products and foodstuffs to clothing, cars, cigarettes, and mobile phones, as well as overseeing cross-border human trafficking operations in cooperation with various entities, especially Hezbollah. [12]

4. Trade and Investment

The Fourth Division has used its clout in the formal economy to generate significant returns from trade and investment, monopolizing the trade and sale of scrap metals such as copper and iron through affiliated merchants. It has focused specifically on plundering metals from areas it raided in military operations, unlike other brigades, which have mainly looted furniture. It has also forced scrap collectors to sell it their scrap at low prices, which is then sent to smelting and rolling plants such as the smelting plant in Hassia and the iron rolling mills there and in Latakia. These facilities are owned by the Sarouh Construction Company, in turn owned by Samer al-Fawz and Emad Hamsho.

Maher al-Assad has used Mohammed Hamsho’s international group of companies as an economic facade for the Fourth Division’s investment activities, such as manufacturing metal products and trading in scrap metal, gas, oil, and more. The European Union [13] and the U.S. Treasury have imposed sanctions on the group, [14] as well as on Ali Khadr’s Group, [15] which Maher al-Assad has also used in various economic activities for the Fourth Division, such as the Syrian Transport and Tourism Company, Emma Tel LLC, and Ella Media Services LLC.

The Fourth Division has thus created its own economic ecosystem, one that constitutes a significant part of the shadow economy and works to finance the division and pay its officers—as well as generating funds for the regime—through drug trafficking and production, monopolistic investment, and money laundering.

4. The Fourth Division’s Relationships

There has been no public indication of a power struggle between the Fourth Division and the presidential palace, nor between Maher and his brother, President Bashar al-Assad. The Division has not moved in any visible way against Bashar al-Assad nor against other army divisions loyal to the palace, unlike the conflict in the 1980s between Hafez al-Assad and his brother Rifaat.

However, the Division has exploited the situation since 2011 to expand its influence and geographical presence, forming an entity that operates in parallel with the presidency. This means that the possibility of a future conflict between the two brothers cannot be ruled out.

The presidency takes care to protect Maher al-Assad’s interests and influence, such as by granting the Division’s senior officers continuous rewards in the form of higher positions and tasks than their roles within and outside the division. It appoints them as heads of military security branches and officers in provincial security committees, thus granting the division privileges over other military units. Despite orders to terminate such officers’ administrative relationships with the division, their ties to Maher al-Assad remain intact; for example, Brigadier General Jamal Younes was the commander of the 555 th Brigade before becoming the head of the security committee in Deir Ezzor.

Similarly, Bashar al-Assad accommodates his brother by directing all senior officials to execute Maher’s orders without question, as if they were issued by the president himself. Additionally, he quickly moved to extinguish a conflict between the presidential palace’s secretive Economic Office, affiliated with First Lady Asma al-Assad, and Maher al-Assad’s his economic network: the president froze his wife’s outfit and barred her and her employees from public activity, while reactivating the Baath Party’s economic office.

However, such policies do not hide the president’s concerns and suspicion that his brother’s influence could expand to the point where they threaten his own powers. He has not granted Maher exceptional promotions since assuming the presidency, apart from appointing him as commander of the Fourth Division in 2018. Nor has he given him any official titles in the Baath Party, besides a seat on its Central Committee alongside 93 other members. Nor has he presented Maher with an easy potential route to the presidency via a constitutional mechanism that would activate in the absence of the president—unlike his father, who appointed Rifaat as a deputy who, under the constitution, would assume the presidency in his own absence. Bashar has refrained from delegating international missions to his brother, despite the Fourth Division’s close relations on the ground with Iran and Hezbollah.

The force has continued to provide cover for the activities of Iran and Hezbollah in many areas where they are deployed, especially in eastern, northern, and central-western Syria. However, it has been involved in limited disagreements and even armed clashes with these forces in Deir Ezzor, Daraa, and on the outskirts of Damascus, although this has not fundamentally affected their cooperation. Iran supplies the Syrian regime’s frontlines with fighters when necessary, and in return, the Fourth Division facilitates the deployment of Iranian-backed militias. For example, Jamal Younes has helped the Division cooperate with Iran in Deir Ezzor, facilitating the purchase of properties by Iran-affiliated traders, opening smuggling routes from Iraq to Syria, and providing logistical support.

The Fourth Division is not opposed to Russian military activity in Syria, as was clear when Maher al-Assad attended a training project supervised by Russian forces in Syria in late 2022. The Fourth Division’s commander understands the importance of Russia’s efforts to restructure and strengthen the regime’s forces as a military institution in any future resolution to the Syrian conflict, something that aligns with his personal drive to enhance the cohesion and dominance of the Fourth Division within that institution. However, he has rejected Russia’s demands to withdraw his force’s checkpoints from Daraa to allow the Fifth Division to operate there instead. Many within the Fourth Division have also accused Russia of involvement in the 2022 bombing of a bus belonging to the division on the Saboura road in Damascus, killed or wounded nearly 40 personnel.

Conclusion

Under Maher al-Assad, the Fourth Division has leveraged the regime’s need for its specialist capabilities to gain influence and extend its presence. It now has a military and security presence in most provinces of Syria, and has acquired a role equivalent to that of the General Staff, including the command of combat operations. It has also created a security architecture that manages the bulk of Syria’s shadow economy, including the production and smuggling of narcotics. This has transformed it into a parallel army with its own resources, arms supplies, security apparatus and relationships with the regime’s allies, specifically Iran.

The Fourth Division has facilitated the deployment of both Iranian and Hezbollah forces across various Syrian provinces, providing them with logistical and military support in exchange for military and economic gains. Wherever these militias are present, the Fourth Division provides them with cover, with the exception of certain areas where Maher al-Assad has taken special measures to take into account Israeli interests in southern Syria and those of the Assad clan’s Alawite sect near the Mediterranean coast.

Thus, the Fourth Division is deeply implicated in Iran and Hezbollah’s illegal activities in Syria, which aim to destabilize regional security, through drug trafficking, arms smuggling, money laundering, and facilitating the activities of militias classified as terrorist organizations. Conversely, deploying alongside the Iranian militias and Hezbollah has enabled the Fourth Division to infiltrate them, meaning that Maher al-Assad has security information regarding all their activities and personnel—a key asset he could potentially use in negotiations with external parties.

Ultimately, the Fourth Division’s growing clout and widespread deployment have turned it into a power center that rivals the authority of the presidential palace. This situation is unprecedented since Rifaat al-Assad went into exile after his failed coup in 1989. Although there are no visible signs that the Division is considering rebelling against the presidency, the situation compels President Bashar al-Assad to avoid any action that would rein in the power of his brother Maher, who has effectively become a co-ruler in the shadows.

[1] “Widespread Looting by Syrian and Iranian Regime Forces in and Around Idlib Threatens the Return of the Displaced People and Sows Religious Hatred,” Syrian Network for Human Rights , March 31, 2020, link .

[2] "Theft of Property: A Systematic Policy Under Official Supervision,” Syrian Human Rights Committee , May 19, 2014 (in Arabic), link .

[3] Ibid.

[4] An archived author interview with a senior opposition figure in the Old City of Homs, whose faction detained a member of the Fourth Division who had dealt with former members of the People’s Assembly and sold them property he had looted from homes in 2014.

[5] Author interview with a trader who previously paid members of the Fourth Division to transport his goods from opposition areas to various cities for fear of them being targeted or stolen, September 17, 2024.

[6] Abdullah Alghadawi, “The Fourth Division: Syria’s parallel army,” Middle East Institute , September 24, 2021, link .

[7] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Continues Targeting Facilitators of Assad Regime,” September 30, 2020, link .

[8] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Syrian Regime and Lebanese Actors Involved in Illicit Drug Production and Trafficking,” March 28, 2023, link .

[9] "A ‘Drug War’: Syria’s Neighbors Fight a Flood of Captagon Across Their Borders,” Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project , June 27, 2023, link .

[10] Habib Abu Mahfouz, “What are Jordan’s options for tackling drug smuggling and infiltration from Syria?” Al Jazeera , September 26, 2023, (in Arabic), link .

[11] “A ‘Drug War’,” OCCRP .

[12] U.S. Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Actors.”

[13] “Factbox: Sanctions imposed on Syria,” Reuters , November 28, 2011, link .

[14] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Prominent Syrian Businessman,” August 4, 2011, link .

[15] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Continues Targeting Facilitators of Assad Regime,” September 30, 2020, link .